Jan 24 2022

Carbon Signatures and Life on Mars

Was there ever or is there currently any life on Mars is one of the biggest scientific questions of our time. If we do manage to find the remnants of life on Mars, we may be able to ask a deeper question – what is the relationship between that life and life on Earth? Are they related or completely independent? This, in turn, informs our speculations about how common life is in the Universe. For how, however, the question about life on Mars in an open one.

Was there ever or is there currently any life on Mars is one of the biggest scientific questions of our time. If we do manage to find the remnants of life on Mars, we may be able to ask a deeper question – what is the relationship between that life and life on Earth? Are they related or completely independent? This, in turn, informs our speculations about how common life is in the Universe. For how, however, the question about life on Mars in an open one.

There are essentially three lines of evidence we can potentially bring to bear to help answer this question. The first, of course, would be the direct detection of extant life on Mars. If little critters are still metabolizing in the soil of Mars we could detect the products of their metabolism, and perhaps even detect the critters themselves. The second method is to detect the conditions for life, either at present or in ancient Mars. It now seems likely, for example, that ancient Mars had liquid water on its surface, which is a very compatible environment for life.

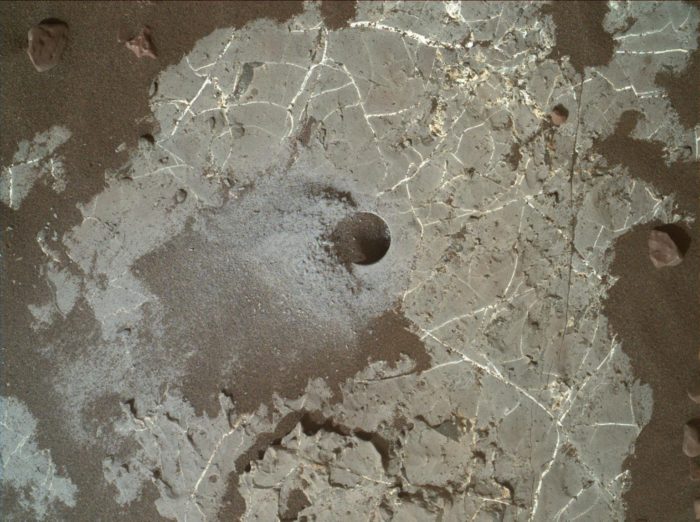

The final method is to detect fossil evidence of life on Mars. This does not have to be literal “fossils” as most people think of the term, meaning petrified bones, but rather some signature of life in the Martian environment. One of the missions of the Perseverence rover on Mars is to look for these signatures, and to prepare samples for possible return to Earth. But don’t forget about the Curiosity rover, which is still roving around Mars. Recently Curiosity concluded an analysis of Martian rock which produced some very – curious – results, that could be a possible signature of past life on Mars (“possible” being the operative word there).

The experiment involved heating 24 different powdered rock samples (some from rock beds known to be ancient) to release gases, then measuring the ratio of C13 to C12 released, and finding a depleted C13 ratio, which could be an indication of life. Some background is needed here. Isotopes are different kinds of an element with different numbers of neutrons. Elements are determined by their number of positively-charged protons, with carbon having six protons. Neutrons have no charge but do affect the total mass of the atoms. The most common isotope of carbon is C12, with six protons and six neutrons. The second most common isotope is C13, with seven neutrons. Both of these isotopes are stable, meaning they do not decay over time.

Not relevant to the current story, but for completeness, C14 with 8 neutrons is created in the atmosphere of Earth through cosmic rays. C14 is unstable, with a half-life of 5,730. Plants will incorporate a little C14 into their structure based on the percent of C14 in the atmosphere, then when they die that C14 with decay over time into nitrogen-14 (one neutron decays into a proton). Therefore we can measure the ratio of C14 to C12 and C13 in a fossil to determine how long ago it died, up to about 50,000 years (then there will be too little C14 to detect reliably). This is carbon dating.

The current story has nothing to do with C14, but rather has to do with the ratio of C12 to C13. These isotopes are chemically identical, but C13 is a little heavier than C12. This causes plants, which breath in carbon and fix it to sugars as their source of energy, to absorb a little more C12 compared to C13 than the ratio in the atmosphere and water. Most of the carbon in the carbon cycle is C12, with 98.8% C12 in the atmosphere. But there is 99.2% in living things – the C13 is a little depleted, making the ratio a little “lighter” (so-called because C12 is lighter than C13). On Earth the carbon cycle is extensively studied and well understood, so we can look at C12-C13 ratios and draw conclusions about the source, specifically whether or not life is involved.

We are now trying to apply this knowledge to Mars. Mars has a thin atmosphere, less than 1% of Earth’s, but it is mostly carbon, and it was much thicker in the past. What the Curiosity experiment found was:

“Included in these data are 10 measured δ13C values less than −70‰ found for six different sampling locations, all potentially associated with a possible paleosurface.”

Essentially they found that some of the samples, all from rocks thought to be ancient, had depleted C13 ratios. One of the possible processes that could deplete the C13 is life, just as on Earth. However, there are at least two other non-life processes that could also deplete C13. One is a chemical process that releases methane. That methane is then broken down by ultraviolet light, releasing carbon-containing molecules into the atmosphere which then rain down on the surface of Mars getting incorporated into the rock and soil. Carbon from this source would be deplete of C13. A third possibility is that at some point in the distant past our solar system moved through a molecular cloud in space, containing C12 that also became incorporated into the Martial soil. The current evidence is compatible with all three hypotheses. Now scientists have to conduct further experiments in order to figure out which one is the cause of the depleted C13 in the Curiosity samples. These follow up experiments is where Perseverence comes into the picture, mostly through samples it is preparing for return to Earth.

The main problem is that we do not yet understand the carbon cycle on Mars, and we cannot assume that it is the same as the carbon cycle on Earth. Also, Earth’s carbon cycle is overwhelmed by the processes of life, so a more subtle chemical process might be obscured entirely. Whereas on Mars those chemical processes may be the entire carbon cycle. Once we understand the Martian carbon cycle more fully, then we can interpret what the various isotope ratios mean. They may not mean what the do on Earth.

Yet again we are stuck, for now, with tantalizing hints of possible life on Mars, but nothing definitive. Sometimes science can be frustratingly slow, but this question is worth pursuing, and it’s good to know that NASA and others are pursuing it.