Jan 18 2022

Are We In a Sixth Extinction

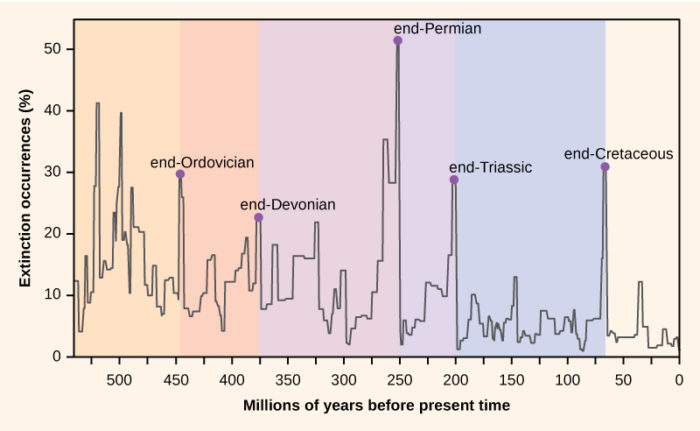

There have been five recognized mass extinctions in the history of life on Earth, and a number of smaller ones. They include, in order:

There have been five recognized mass extinctions in the history of life on Earth, and a number of smaller ones. They include, in order:

- Ordovician (444 million years ago; mya) – climate change caused by continental drift

- Devonian (360 mya) – volcanic eruptions

- Permian (250 mya) – unknown, could be asteroid strike, eruptions, climate change

- Triassic-Jurassic (200 mya) – volcanic activity

- KT (65 mya) – asteroid strike

Many scientists believe we are now in the middle of a sixth mass extinction, this time cause entirely by anthropogenic factors – human activity. We are warming the atmosphere and oceans, acidifying the oceans, polluting the environment, overfishing, hunting some species to extinction, converting ecosystems to farmland and living space, and spreading invasive species. The evidence of a slow-rolling mass extinction seems to be obvious, but still there are those who question if it is really happening. That questioning ranges from healthy scientific skepticism to outright denial.

The reason for the debate is our ability to rigorously document the extinction rate over time. It’s not enough to point out that extinctions are happening. The current estimate is that there are 8.7 million species of plants and animals extant today. Extinction is also a natural part of the evolution of life over time, and biologists also estimate that the background extinction rate is about 10% every million years. This can also be expressed as one extinction per million species years (one extinction per million species per year). This means the background rate should be about 870 extinctions per century. Over the last century there have been recorded about 500 animal extinctions. This is the basis for the argument that we are not in the middle of a mass extinction.

However, both estimates – the background extinction rate and the current extinction rate – are in question, and this is where the real debate is happening. Estimating the background extinction rate is tricky, mostly based on surveys of fossils. A 2015 paper puts the estimate at closer to 0.1 extinctions per million species years (E/MSY), down from the older estimate of 1 E/MSY. If true then we are currently running at ten times the background rate. But wait, we may also be experiencing far more extinctions than are documented.

The record is biased toward documenting extinctions of mammals and birds, and is extremely lacking in terms of invertebrates and plants. A new study seeks to rectify the discrepancy by systematically reviewing the evidence. The found, for example:

As an example, we focus on molluscs, the second largest phylum in numbers of known species, and, extrapolating boldly, estimate that, since around AD 1500, possibly as many as 7.5–13% (150,000–260,000) of all ~2 million known species have already gone extinct, orders of magnitude greater than the 882 (0.04%) on the Red List.

The Red List refers to the IUCN Red List which documents all threatened species. There are clearly a range of estimates for both the background and current extinction rates. But taking even the middle of both ranges, there appears to currently be extinctions hundreds of times the background rate, with the upper limit being thousands of times. But there is always a degree of uncertainty with scientific evidence, and that is where denial lives. I like the brief explanation that the authors give differentiating skepticism from denial:

Denial differs from scepticism. The latter is a genuine component of scientific research and discovery, questioning assumptions, results, interpretations and conclusions, until the weight of evidence supports one conclusion or another. Denial, on the other hand is plain disbelief in that weight of evidence.

There is also another issue that we have to consider – loss of biodiversity. Many biologists are concerned not only about the species we have already lost, but those that are likely to go extinct in the next thousand years or so. Keep in mind that “extinction events” are characterized by a significant increase in the background extinction rate over 1-2 million years, which is a short time on geological timescales. Causing significant extinctions over thousands of years is relatively fast, by the standard of most historic mass extinctions (excluding those caused by giant impacts).

We have good reason to think that future extinctions will be significant. When the biodiversity of a species is significantly reduced, the probability that they will go extinct over the next 1,000 years becomes extremely high. They may squeak through, but we are talking probability. There are many species now that are threatened due to habitat loss causing a significant reduction in their absolute numbers and biodiversity. Most of these species are likely to go extinct in the next thousand years.

Also, none of the environmental problems I listed above are getting better. They are all getting worse. The effects may not be dramatic over a human lifetime, which is why we need collective memory and scientific investigation to document what is happening over centuries and millennia. If we want to continue to inhabit a planet with rich biodiversity, it is in our own interests to consider and mitigate the impact we are having.