Mar

09

2021

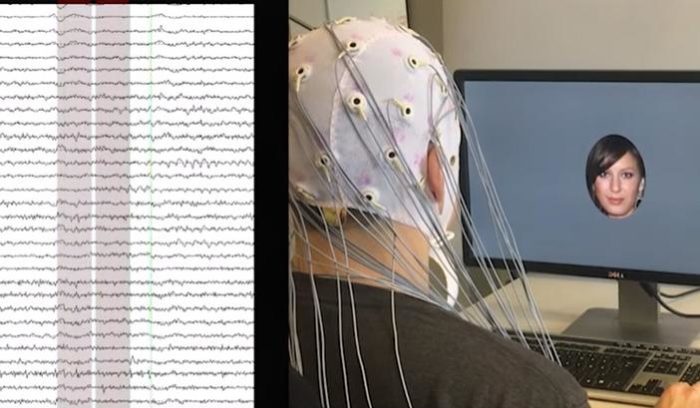

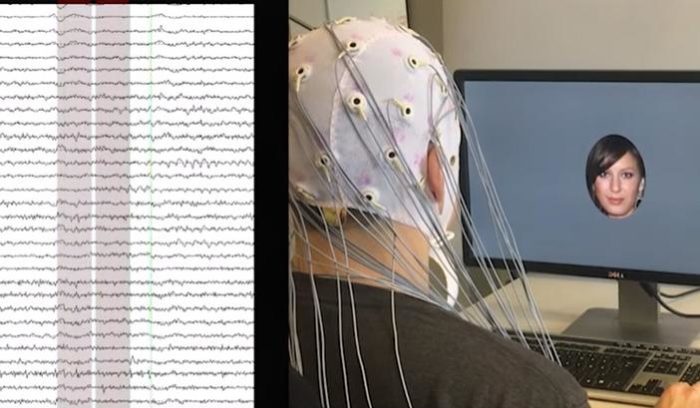

I have been tracking the research in brain-machine interface (BMI), specifically with an eye towards studies that claim to interpret brain data. Typically I find that such studies are overhyped, at least in the press release and subsequent reporting. The question I always ask myself is – what exactly are they measuring and interpreting? A new study, using BMI and a form of AI called Generative adversarial neural networks (GANs), claims to read brain data to determine what faces subjects find attractive. What are the researchers doing, and what are they not doing?

I have been tracking the research in brain-machine interface (BMI), specifically with an eye towards studies that claim to interpret brain data. Typically I find that such studies are overhyped, at least in the press release and subsequent reporting. The question I always ask myself is – what exactly are they measuring and interpreting? A new study, using BMI and a form of AI called Generative adversarial neural networks (GANs), claims to read brain data to determine what faces subjects find attractive. What are the researchers doing, and what are they not doing?

The ultimate goal of BMI research (or at least one goal) is to figure out how to interpret brain activity so well that it is essentially mind-reading. For example, you might think of the word “cromulent” and a machine reading the resulting brain activity will be able to interpret it so well that it can generate the word “cromulent”. This would make possible a fully functional digitial-neural interface, like in The Matrix. To be clear – we are no where near this goal.

We have picked some of the low-hanging fruit, which are those areas of the brain that function through some form of somatotopic mapping. Vision is the most obvious example – if you are looking at the letter “F”, neurons in the visual cortex in the literal shape of an “F” will become active. Visual processing is much more complex than this, but at some level there is this bitmap level of representation. The motor and sensory parts of the brain also follow somatotopic mapping (the so-called homonculus for each). There is likely also a map for auditory processing, but more complex and we don’t fully understand it.

The big question is – what are the conceptual maps? Physical maps representing space, images, even sound frequencies, are easy to understand. What are the neural map for words, feelings, or abstract concepts? Related to this is the concept of embodied cognition – that our reasoning derives ultimately from our understanding of the physical world. We use physical metaphors to represent abstract concepts. For example, an argument can be “strong” or “weak”, your boss is hierarchically “above” you, you may have “gone too far” with a wild idea that is a “stretch”. This may just be how languages evolved, but the idea of embodied cognition is that the language represents something deeper about how our brains work. Perhaps even abstract concepts are physically mapped in the brain, anchoring even our abstract thoughts to a physical reality. Perhaps embodied cognition is not absolute, but more of a bridge between the physical and the abstract, or a scaffold on which fully abstract ideas can be cortically mapped. We are a long way from sorting all this out.

Continue Reading »

Mar

08

2021

We know a lot more now about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 than we did a year ago when this pandemic was just getting into full swing. One of the big questions was about the emergence of new variants – how fast does the virus mutate, and what is the probability of variants with new properties emerging? Scientists have been tracking the variants since the beginning. It’s actually a good way to track the spread of the virus, and our ability to sequence the genome of specific viruses is fairly advanced.

We know a lot more now about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 than we did a year ago when this pandemic was just getting into full swing. One of the big questions was about the emergence of new variants – how fast does the virus mutate, and what is the probability of variants with new properties emerging? Scientists have been tracking the variants since the beginning. It’s actually a good way to track the spread of the virus, and our ability to sequence the genome of specific viruses is fairly advanced.

As of August 2020 scientists had identified six strains or variants of SARS-CoV-2, without any significant difference in biological function among them. This was encouraging – the hope was that this virus mutates slowly and that no functionally new versions would emerge. This is important for two reasons. The first is the question of whether or not someone who has already suffered COVID-19 or been infected without symptoms could become reinfected. This is partly about the strength of the immune response to infection, but also about whether or not new strains would be able to bypass immunity to older strains.

However, by the beginning of 2021 two things were happening, one good, one bad. Vaccine distribution was ramping up. Several vaccines were approved toward the end of 2020 and while initial distribution was slow, it is speeding up. By now almost 59 million Americans have received at least one dose of a vaccine, and we are being promised availability for everyone who wants a vaccine by May. At the same time daily new cases of COVID are dropping fast, although still relatively high compared to the Spring and Summer of 2020.

But the bad news is that three new variants of SARS-CoV-2 have now been identified that are functionally different – one identified in the UK, one in South Africa, and one in Brazil. These variants have several mutations affecting the structure of the spike protein that gives coronavirus its name, and is responsible for its ability to infect cells. Spike proteins are also a target of antibodies produced by infection or vaccine. As news about these variants comes dripping it, it’s not good. All three appear to be more infectious. They spread more easily than the older variants, which means more robust protection might be necessary to prevent spread. Further, because of their increased infectivity, they are rapidly becoming the dominant strains where they spread.

Continue Reading »

Mar

04

2021

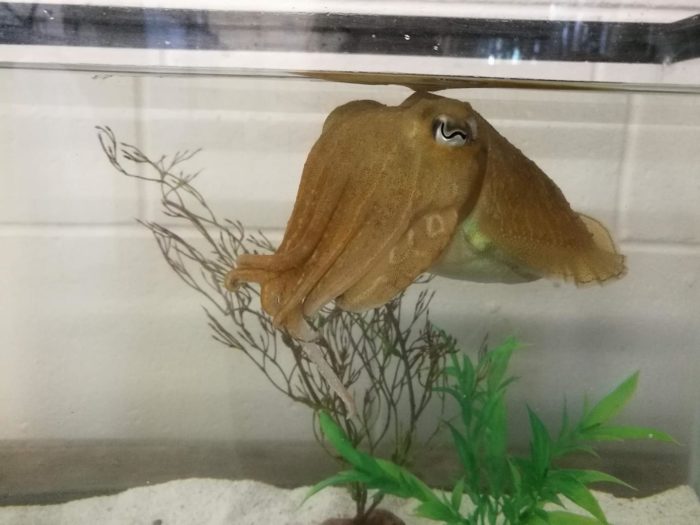

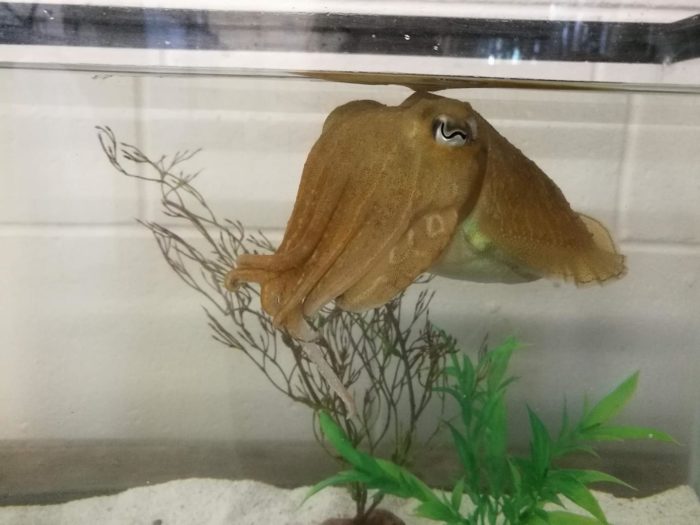

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can pass the marshmallow test.

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can pass the marshmallow test.

The “marshmallow test” is a psychological experiment of the ability to delay gratification. The basic study involves putting a treat (like a marshmallow, but it can be anything) in front of a young child and telling them they can have it now, or they can wait until the adult returns at which time they will be given two treats. The question is – how long can children hold out in order to double their treats? The interesting part of this research paradigm are all the associated factors. Older children can hold out longer than younger children. The greater the reward, the more children can wait for it. Children who find ways to distract themselves can hold out longer.

For decades the test and all its variations was interpreted as a measure of executive function, and correlated with all sorts of things like later academic and economic success. However, more recent studies have found (unsurprisingly) that there can be confounding factors not previously recognized. For example, children from insecure environments have not reason to trust that adults will return with more treats and therefore take what is in front of them. This could be seen as an adaptive response to their environment.

Continue Reading »

Mar

02

2021

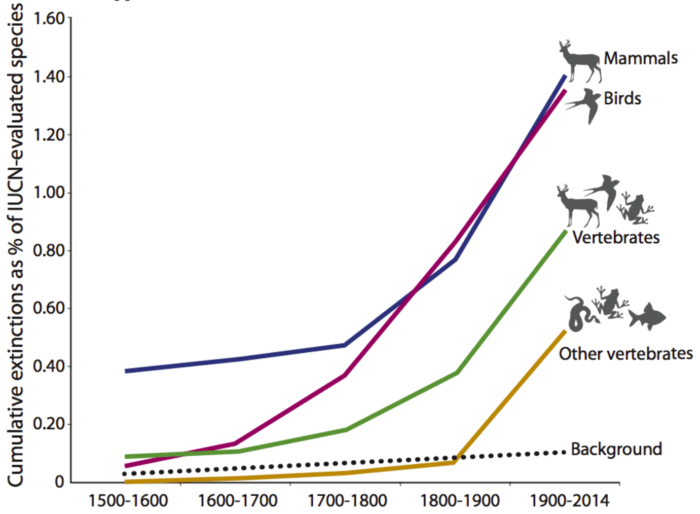

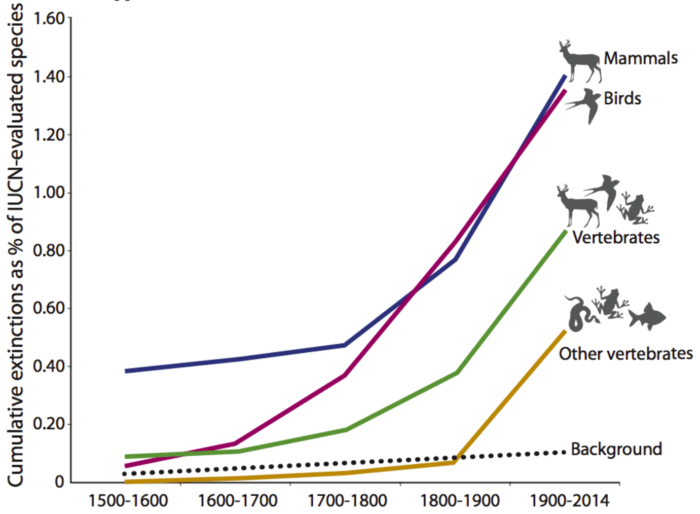

One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why?

One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why?

I recently wrote about the North American megafauna, and the debate between whether their extinction about 12 thousands years ago was caused primarily by humans (the overkill hypothesis) or climate change. But this debate exists for the entire planet – every continent except Antarctica. This continues to be a debate because large-scale cause and effect is difficult to prove in evolutionary history. We can test various hypotheses by predicting correlations and patterns in the fossil record and then looking for them. Sometimes we can extrapolate from current observable trends, or even changes in the laboratory. But the steady reduction in the average size of mammals requires looking for large correlations – what factor does this trend most have in common around the world? Many scientists think the clear answer is – humans.

Starting with Homo erectus, wherever humans go around the world they are followed by a wave of megafauna extinction. Could this just be a general trend unrelated to humans? Perhaps the world’s climate has been changing in such a way over the last two million years that explains a selective advantage to small size. Climate cannot be ruled out as a factor, but the evidence increasingly supports the notion that human hunting played a major factor.

I am always suspicious of nice clean stories in evolution, so I will add a huge caveat that any hypothesis about A causing B is likely to be a massive oversimplification. But some factors can have dominant effects. Around 2 million years ago we start to see the first evidence of Homo erectus using fire. At this same time erectus clearly dramatically ramped up their hunting, and also this was the first time a human species spread throughout the world. Cooking meat would have been a huge energy and nutritional advantage, and hunting requires a lot of land, and hence the need to spread out. This shift in our human ancestors correlates nicely with dramatic reductions in the average size of mammals, wherever humans went.

Continue Reading »

Mar

01

2021

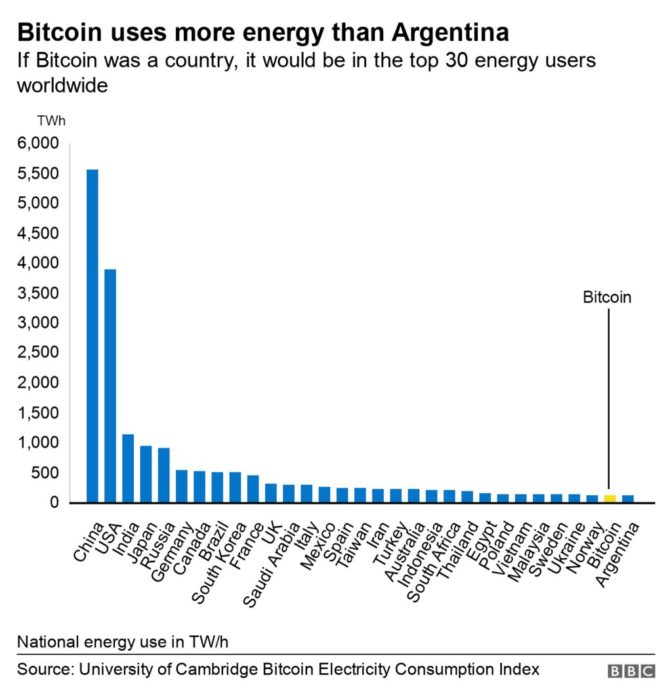

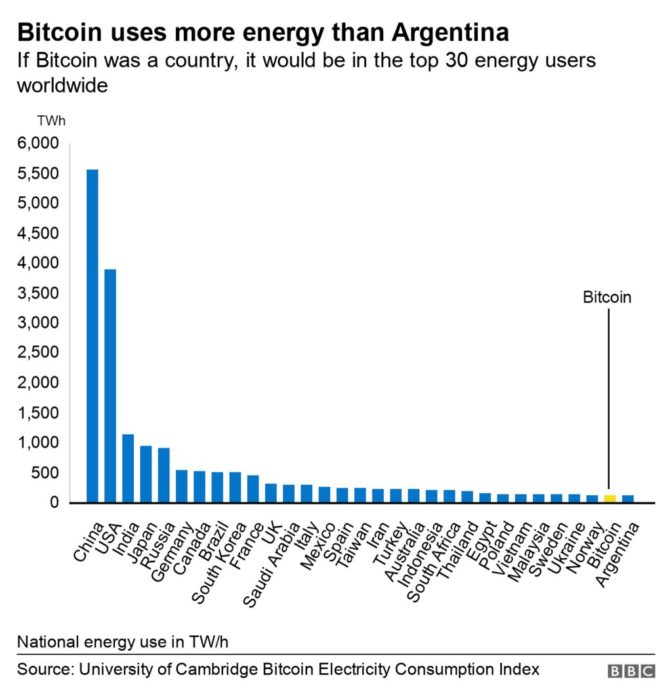

We are approaching 8 billion people on this planet, and so anything that a lot of people do is likely to have a significant impact. This includes things that we previously considered to be essentially resource free, or at least insignificant, including digital activity. This may be a bit of a generational thing – those of us who lived through the explosion of computer use, the adoption of the web and social media, and the general shift from analog to digital technology grew up with the idea that doing things digitally was resource efficient.

We are approaching 8 billion people on this planet, and so anything that a lot of people do is likely to have a significant impact. This includes things that we previously considered to be essentially resource free, or at least insignificant, including digital activity. This may be a bit of a generational thing – those of us who lived through the explosion of computer use, the adoption of the web and social media, and the general shift from analog to digital technology grew up with the idea that doing things digitally was resource efficient.

For example, there was a huge push to transform to a “paperless office” because that would save trees. It is much better to shuffle electrons around than pieces of paper. This transition took a lot longer than anyone thought, and in fact – it hasn’t really happened yet. Here we are, 40 years later, and office paper use is still increasing. No one would have predicted that.

Because of the pandemic meetings and many services shifted from in-person to online, over Zoom, for example. This is much more efficient than people traveling to the same physical location for the meeting. But this does not mean we can ignore the electricity use, and therefore carbon footprint, of the digital meeting. A recent study, for example, found that simply turning off the video when not needed can reduce that footprint by 96%. This is small individually, but huge in the aggregate:

Turning off a camera for 15 hour-long meetings every week would reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 9.4 kilograms (20.7 pounds) per month. If one million Zoom users did this, they would save 9,000 tons of CO2, the equivalent of coal-powered energy used by a city of 36,000 in that same month.

Continue Reading »

I have been tracking the research in brain-machine interface (BMI), specifically with an eye towards studies that claim to interpret brain data. Typically I find that such studies are overhyped, at least in the press release and subsequent reporting. The question I always ask myself is – what exactly are they measuring and interpreting? A new study, using BMI and a form of AI called Generative adversarial neural networks (GANs), claims to read brain data to determine what faces subjects find attractive. What are the researchers doing, and what are they not doing?

I have been tracking the research in brain-machine interface (BMI), specifically with an eye towards studies that claim to interpret brain data. Typically I find that such studies are overhyped, at least in the press release and subsequent reporting. The question I always ask myself is – what exactly are they measuring and interpreting? A new study, using BMI and a form of AI called Generative adversarial neural networks (GANs), claims to read brain data to determine what faces subjects find attractive. What are the researchers doing, and what are they not doing?

We know a lot more now about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 than we did a year ago when this pandemic was just getting into full swing. One of the big questions was about the emergence of new variants – how fast does the virus mutate, and what is the probability of variants with new properties emerging? Scientists have been tracking the variants since the beginning. It’s actually a good way to track the spread of the virus, and our ability to sequence the genome of specific viruses is fairly advanced.

We know a lot more now about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 than we did a year ago when this pandemic was just getting into full swing. One of the big questions was about the emergence of new variants – how fast does the virus mutate, and what is the probability of variants with new properties emerging? Scientists have been tracking the variants since the beginning. It’s actually a good way to track the spread of the virus, and our ability to sequence the genome of specific viruses is fairly advanced. Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can  One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why?

One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why? We are approaching 8 billion people on this planet, and so anything that a lot of people do is likely to have a significant impact. This includes things that we previously considered to be essentially resource free, or at least insignificant, including digital activity. This may be a bit of a generational thing – those of us who lived through the explosion of computer use, the adoption of the web and social media, and the general shift from analog to digital technology grew up with the idea that doing things digitally was resource efficient.

We are approaching 8 billion people on this planet, and so anything that a lot of people do is likely to have a significant impact. This includes things that we previously considered to be essentially resource free, or at least insignificant, including digital activity. This may be a bit of a generational thing – those of us who lived through the explosion of computer use, the adoption of the web and social media, and the general shift from analog to digital technology grew up with the idea that doing things digitally was resource efficient.