Sep 29 2020

COVID – Not Close to Herd Immunity

One question weighing on the minds of many people today is – when will this all end? And by “this” (well, one of the “thises”) I mean the pandemic. Experts have been saying all along that we need to buckle up and get read for a long ride on the pandemic express. This is a marathon, and we need to be psychologically prepared for what we are doing now being the new normal for a long time. The big question is – what will it take to end the pandemic?

One question weighing on the minds of many people today is – when will this all end? And by “this” (well, one of the “thises”) I mean the pandemic. Experts have been saying all along that we need to buckle up and get read for a long ride on the pandemic express. This is a marathon, and we need to be psychologically prepared for what we are doing now being the new normal for a long time. The big question is – what will it take to end the pandemic?

Many people are pinning their hopes on a vaccine (or several). This is probably our best chance, and the world-wide effort to quickly develop possible vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 has been impressive. There are currently 11 vaccines in late stage Phase 3 clinical trials. There are also 5 vaccines approved for limited early use. No vaccines are yet approved for general use. If all goes well we might expect one or more vaccines to have general approval by the end of the year, which means wide distribution by the end of 2021. That is, if all goes well. This is still new, and we are fast-tracking this vaccine. This is not a bad thing and does not necessarily mean we are rushing it, but it means we won’t know until we know. Scientists need to confirm how much immunity any particular vaccine produces, and how long it lasts. We also need to track them seriously for side effects.

Early on there was much speculation about the pandemic just burning itself out, or being seasonal and so going away in the summer. Neither of these things happened. In fact, the pandemic is giving the virus lots of opportunity to mutate, and a new more contagious strain of the virus has been dominating since July. Pandemics do eventually end, but that’s not the same as them going away. Some viruses just become endemic in the world population, and they come and go over time. We now, for example, just live with the flu, and with HIV. So perhaps COVID will just be one more chronic illness plaguing humanity that we have to deal with.

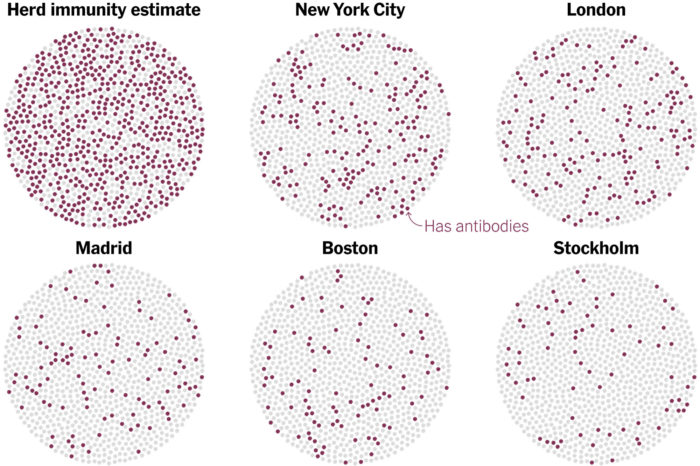

But what about herd immunity? The point of an aggressive vaccine program is to create herd immunity – giving so many people resistance that the virus has difficulty finding susceptible hosts and cannot easily spread. The percent of the population with immunity necessary for this to happen depends on how contagious the infectious agent is, and ranges from about 50-90%. We don’t know yet where COVID-19 falls, but this is a contagious virus so will probably be closer to 90%. One question is, how much immunity is the pandemic itself causing, and will we naturally get to herd immunity, even without a vaccine? The results of a new study suggest the answer is no.

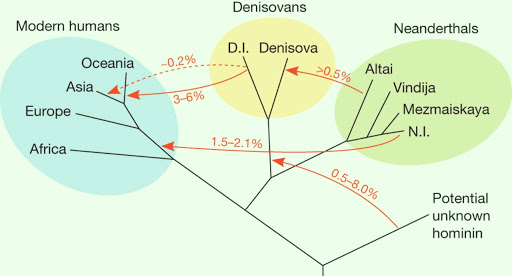

Recent human ancestry remains a complex puzzle, although we are steadily filling in the pieces. For the first time

Recent human ancestry remains a complex puzzle, although we are steadily filling in the pieces. For the first time

Drugs are regulated in most countries for a reason. They can have powerful effects on the body, can be particularly risky or are incompatible with certain diseases, and can interact with other drugs. Dosages also need to be determined and monitored. So most countries have concluded that prescriptions of powerful drugs should be monitored by physicians who have expertise in their effects and interactions. Some drugs are deemed safe enough that they can be taken over the counter without a prescription, usually in restricted doses, but most require a prescription. Further, before going on the market drug manufacturers have to thoroughly study a drug’s pharmacological activity and determine that it is safe and effective for the conditions claimed. There is a balance here of risk vs benefit – making useful drugs available while taking precautions to minimize the risk of negative outcomes.

Drugs are regulated in most countries for a reason. They can have powerful effects on the body, can be particularly risky or are incompatible with certain diseases, and can interact with other drugs. Dosages also need to be determined and monitored. So most countries have concluded that prescriptions of powerful drugs should be monitored by physicians who have expertise in their effects and interactions. Some drugs are deemed safe enough that they can be taken over the counter without a prescription, usually in restricted doses, but most require a prescription. Further, before going on the market drug manufacturers have to thoroughly study a drug’s pharmacological activity and determine that it is safe and effective for the conditions claimed. There is a balance here of risk vs benefit – making useful drugs available while taking precautions to minimize the risk of negative outcomes. The issue of genetically modified organisms is interesting from a science communication perspective because it is the one controversy that apparently most follows the old knowledge deficit paradigm. The question is – why do people reject science and accept pseudoscience. The knowledge deficit paradigm states that they reject science in proportion to their lack of knowledge about science, which should therefore be fixable through straight science education. Unfortunately, most pseudoscience and science denial does not follow this paradigm, and are due to other factors such as lack of critical thinking, ideology, tribalism, and conspiracy thinking. But opposition to GMOs does appear to largely result from a knowledge deficit.

The issue of genetically modified organisms is interesting from a science communication perspective because it is the one controversy that apparently most follows the old knowledge deficit paradigm. The question is – why do people reject science and accept pseudoscience. The knowledge deficit paradigm states that they reject science in proportion to their lack of knowledge about science, which should therefore be fixable through straight science education. Unfortunately, most pseudoscience and science denial does not follow this paradigm, and are due to other factors such as lack of critical thinking, ideology, tribalism, and conspiracy thinking. But opposition to GMOs does appear to largely result from a knowledge deficit. In the movie Interstellar, which takes place in a dystopian future where the Earth is challenged by progressive crop failures, children are taught in school that the US never went to the Moon, that it was all a hoax. This is a great thought experiment – could a myth, even a conspiracy theory, rise to the level of accepted knowledge? In the context of religion the answer is, absolutely. We have seen this happen in recent history, such as with Scientology, and going back even a little further with Mormonism and Christian Science. But what is the extent of the potential contexts in which a rewriting of history within a culture can occur? Or, we can frame the question as – are there any limits to such rewriting of history?

In the movie Interstellar, which takes place in a dystopian future where the Earth is challenged by progressive crop failures, children are taught in school that the US never went to the Moon, that it was all a hoax. This is a great thought experiment – could a myth, even a conspiracy theory, rise to the level of accepted knowledge? In the context of religion the answer is, absolutely. We have seen this happen in recent history, such as with Scientology, and going back even a little further with Mormonism and Christian Science. But what is the extent of the potential contexts in which a rewriting of history within a culture can occur? Or, we can frame the question as – are there any limits to such rewriting of history? I just watched the Netflix documentary, The Social Dilemma, and found it extremely interesting, if flawed. The show is about the inside operation of the big social media tech companies and the impact they are having on society. Like all documentaries – this one has a particular narrative, and that narrative is a choice made by the filmmakers. These narratives never reflect the full complexity of reality, and often drive the viewer to a certain conclusion. In short, you can never take them at face value and should try to understand them in a broader context.

I just watched the Netflix documentary, The Social Dilemma, and found it extremely interesting, if flawed. The show is about the inside operation of the big social media tech companies and the impact they are having on society. Like all documentaries – this one has a particular narrative, and that narrative is a choice made by the filmmakers. These narratives never reflect the full complexity of reality, and often drive the viewer to a certain conclusion. In short, you can never take them at face value and should try to understand them in a broader context. On the surface this is a story of a fantastic paleontological find. Reindeer herders

On the surface this is a story of a fantastic paleontological find. Reindeer herders  This is definitely the big news of the week –

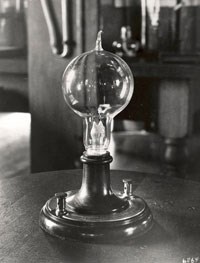

This is definitely the big news of the week – The question of who should get credit for inventing the lightbulb is deceptively complex, and reveals several aspects of the history of science and technology worth revealing. Most people would probably answer the question – Thomas Edison. However, this is more than just overly simplistic. It is arguably wrong. This question has also become political, made so when presidential candidate Joe Biden claims that a black man invented the lightbulb, not Edison. This too is wrong, but is perhaps as correct as the claim that Edison was the inventor.

The question of who should get credit for inventing the lightbulb is deceptively complex, and reveals several aspects of the history of science and technology worth revealing. Most people would probably answer the question – Thomas Edison. However, this is more than just overly simplistic. It is arguably wrong. This question has also become political, made so when presidential candidate Joe Biden claims that a black man invented the lightbulb, not Edison. This too is wrong, but is perhaps as correct as the claim that Edison was the inventor.