May 11 2020

Likely No Summer Break from COVID-19

As is often pointed out, the SARS-CoV2 virus is new, and therefore we have limited data on its characteristics, as well as the disease it causes, COVID-19. This complicates our modeling of what is likely to happen, and recommendations about best practices. But scientists around the world are busy studying this pandemic as it is occurring, and therefore our models and recommendations are evolving.

As is often pointed out, the SARS-CoV2 virus is new, and therefore we have limited data on its characteristics, as well as the disease it causes, COVID-19. This complicates our modeling of what is likely to happen, and recommendations about best practices. But scientists around the world are busy studying this pandemic as it is occurring, and therefore our models and recommendations are evolving.

Already we know quite a bit. For example, one review of NYC patients found:

Among the 393 patients, the median age was 62.2 years, 60.6% were male, and 35.8% had obesity. The most common presenting symptoms were cough (79.4%), fever (77.1%), dyspnea (56.5%), myalgias (23.8%), diarrhea (23.7%), and nausea and vomiting (19.1%). Most of the patients (90.0%) had lymphopenia, 27% had thrombocytopenia, and many had elevated liver-function values and inflammatory markers. Between March 3 and April 10, respiratory failure leading to invasive mechanical ventilation developed in 130 patients (33.1%); to date, only 43 of these patients (33.1%) have been extubated. In total, 40 of the patients (10.2%) have died, and 260 (66.2%) have been discharged from the hospital; outcome data are incomplete for the remaining 93 patients (23.7%).

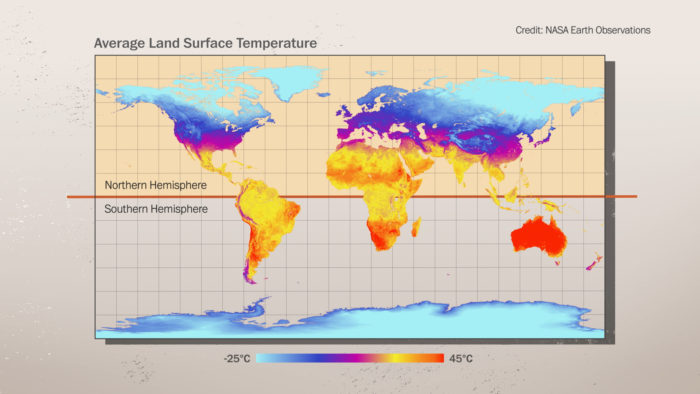

One question, which is especially important as the northern hemisphere approaches summer, is if SARS-CoV2 is less virulent in warmer temperatures. Coronaviruses in general tend to spread less in warmer months, so there is some reason to hope this will be the case. However, a new review of COVID-19 data pokes a hole in this hope. The authors looked at many countries around the world and correlated the number of new cases with various factors, including temperature and humidity.

To estimate epidemic growth, researchers compared the number of cases on March 27 with cases on March 20, 2020, and determined the influence of latitude, temperature, humidity, school closures, restrictions of mass gatherings and social distancing measured during the exposure period of March 7 to 13.

They found no correlation between the number of cases and temperature, and only a weak association of reduced spread with increased humidity. This is, perhaps, the most comprehensive study to date. There have been numerous previous studies, mostly regional, that do show a negative correlation with virus spread and temperature. The authors suggest this is due partly to lack of rigor in those studies. Also, an expert review of this data (prior to the most recent study) urged caution. They note that the studies showed inconsistent results, and it is difficult to generalize the data to what is likely to happen in the world with COVID-19.

In journalism “burying the lede” means that the truly newsworthy part of a story is not mentioned until deep in the story, rather than up front where it belongs. I tried to find if there is a term that means the opposite – to take something that is not really part of the story and present it as if it the lede.

In journalism “burying the lede” means that the truly newsworthy part of a story is not mentioned until deep in the story, rather than up front where it belongs. I tried to find if there is a term that means the opposite – to take something that is not really part of the story and present it as if it the lede.

When I was in college I had just finished a course on social psychology (certainly one of the most memorable courses I took in college), and while back home I was visiting with my then girlfriend. When I arrived they were in the middle of dealing with a door-to-door textbook salesperson. That’s right – the product was a mathematics textbook that combined the K-12 curriculum into one giant tome. My girlfriend’s parents asked my advice, so I sat down to listen to the spiel.

When I was in college I had just finished a course on social psychology (certainly one of the most memorable courses I took in college), and while back home I was visiting with my then girlfriend. When I arrived they were in the middle of dealing with a door-to-door textbook salesperson. That’s right – the product was a mathematics textbook that combined the K-12 curriculum into one giant tome. My girlfriend’s parents asked my advice, so I sat down to listen to the spiel. We appear to be at the beginning of the end of the first wave of COVID-19 (at least in the US – other countries are at different places). We are at the point where states are starting to relax the physical distancing requirements, and there is discussion about how to transition to the next phase. That next phase might include disease tracking, targeted isolation, and “immunity passports.” But planning this next phase is complicated by the fact that we still do not fully understand this virus. We don’t know if there will be a second wave (or more), if it is seasonal, and if you can catch it twice. How we handle this next phase will likely determine if there is a second wave.

We appear to be at the beginning of the end of the first wave of COVID-19 (at least in the US – other countries are at different places). We are at the point where states are starting to relax the physical distancing requirements, and there is discussion about how to transition to the next phase. That next phase might include disease tracking, targeted isolation, and “immunity passports.” But planning this next phase is complicated by the fact that we still do not fully understand this virus. We don’t know if there will be a second wave (or more), if it is seasonal, and if you can catch it twice. How we handle this next phase will likely determine if there is a second wave. This is a very cool study, with the massive caveat that it is extremely preliminary – but

This is a very cool study, with the massive caveat that it is extremely preliminary – but