Apr 30 2019

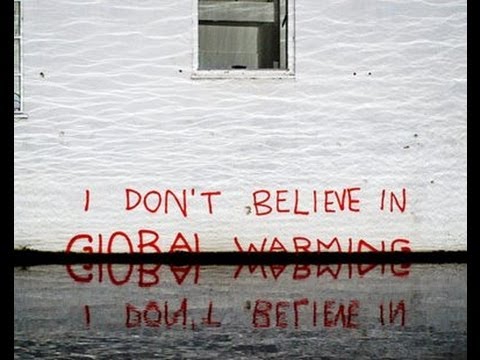

Skeptic vs Denier

The skeptic vs denier debate won’t go away. I fear the issue is far too nuanced for a broad popular consensus. But that should not prevent a consensus among science communicators, who should have a technical understanding of terminology.

The skeptic vs denier debate won’t go away. I fear the issue is far too nuanced for a broad popular consensus. But that should not prevent a consensus among science communicators, who should have a technical understanding of terminology.

A recent editorial in Forbes illustrates the problem. The author, Brian Brettschneider, makes a recommendation for when to use which term, which sounds superficially reasonable but I think he misses the essence of the issue. His solution is this – if you have an advanced degree in climate science and you have doubts about the mainstream view, then you are given the benefit of the doubt and should be referred to as a skeptic. If you do not have a formal degree in climate science, then you have no business going against the consensus of mainstream scientific opinion and you should not be given the benefit of the doubt, and are hence a denier.

This is not a bad rule of thumb as an initial assumption, but does not work as a technical distinction.

First let me say that I agree with the underlying premise. It is not a logical fallacy (argument from authority) to defer to a strong consensus of legitimate expert opinion if you yourself lack appropriate expertise. Deference should be the default position, and your best bet is to understand what that consensus is, how strong is it, and what evidence supports it. Further, if there appears to be any controversy then – who is it, exactly, who does not accept the mainstream consensus, what is their expertise, what are their criticisms, and what is the mainstream response? More importantly – how big is the minority opinion within the expert community.

This is where a bit of judgment comes in, and there is simply no way of avoiding it. There is no simple algorithm to tell you what to believe, but there are some useful rules. Obviously, the stronger the consensus, the more it is reasonable to defer to it. There is always going to be a 1-2% minority opinion on almost any scientific conclusion, that is not sufficient reason to doubt the consensus. But you also need to find out what, exactly the consensus is, and what is just a working hypothesis. Any complex theory will have multiple parts, and it’s not all a package deal.

For example, let’s take evolutionary theory. There is almost unanimous consensus (>98%) among experts that evolution happened, that all living things on Earth are related through a nestled hierarchy of common descent. Further, the evidence for that conclusion is overwhelming and cannot be reasonably denied. Further still, there is no alternative scientific hypothesis that can account for that mountain of evidence (note the word “scientific” in that sentence). But the same is not true of all aspects of evolutionary theory. That natural selection is a main driving force of evolutionary change is also well established, but there is still legitimate debate about the role and magnitude of other factors, such as genetic drift. When we drill down to details about which species evolved into which other species and when, drawing a precise tree of evolutionary relationships, then there is considerable debate and much that is unknown.

As technology advances we find better and better ways to use existing materials. However, material science has the potential to introduce new materials to the equation, changing the game. It’s ironic that news about new materials tends to get relatively little attention in the media, but perhaps has the greatest potential to change our world.

As technology advances we find better and better ways to use existing materials. However, material science has the potential to introduce new materials to the equation, changing the game. It’s ironic that news about new materials tends to get relatively little attention in the media, but perhaps has the greatest potential to change our world. I finally watched

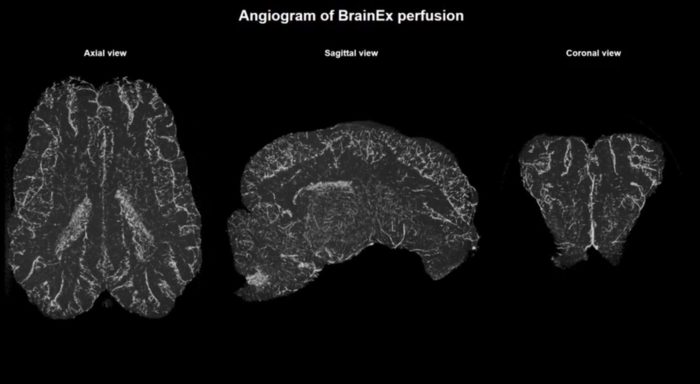

I finally watched  I turns out they were only “mostly dead.” Well, it depends on your definition of death.

I turns out they were only “mostly dead.” Well, it depends on your definition of death. Probably – but it’s complicated.

Probably – but it’s complicated. The FDA has released its guidelines

The FDA has released its guidelines I love the conversation stemming from

I love the conversation stemming from Over the years I have waxed and waned in terms of my optimism that one day flying cars will be a reality – and not just prototypes, but in general use for transportation. I was at an ebb in my enthusiasm, but a recent article has nudged me toward more optimism.

Over the years I have waxed and waned in terms of my optimism that one day flying cars will be a reality – and not just prototypes, but in general use for transportation. I was at an ebb in my enthusiasm, but a recent article has nudged me toward more optimism.

In 2017 Chinese scientists published a paper in the journal Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion titled, “

In 2017 Chinese scientists published a paper in the journal Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion titled, “