Jun 13 2023

Woman with Catatonia for Years Wakes After Treatment

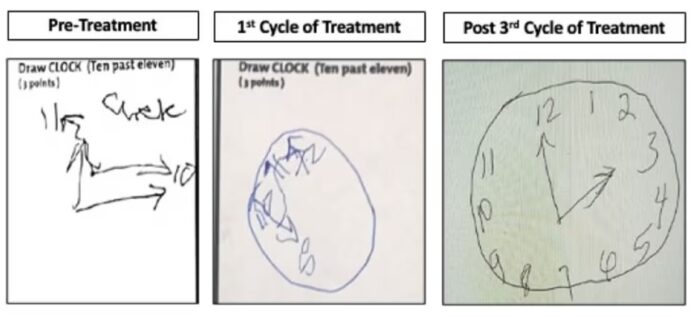

The story of a woman, in a severe state of catatonia for years and “waking up” after being treated for an autoimmune disease, is making the rounds and deserves a little bit of context. April Burrell was diagnosed with a severe form of schizophrenia resulting in catatonia, and has been in long term care since 2000. However, she was also more recently found to have lupus, an autoimmune disease that can affect the brain. After being treated with immunosuppressive medications, multiple courses of treatment over months, her condition steadily improved. She still has symptoms of psychosis and is not cognitively normal, but is able to recognize people and interact and does much better on standard cognitive tests. The credit for her recovery goes to a psychiatrist, Sander Markx, who had seen the patient 20 years before, and upon learning that she was still institutionalized and unchanged order the workup that resulted in the diagnosis.

The story of a woman, in a severe state of catatonia for years and “waking up” after being treated for an autoimmune disease, is making the rounds and deserves a little bit of context. April Burrell was diagnosed with a severe form of schizophrenia resulting in catatonia, and has been in long term care since 2000. However, she was also more recently found to have lupus, an autoimmune disease that can affect the brain. After being treated with immunosuppressive medications, multiple courses of treatment over months, her condition steadily improved. She still has symptoms of psychosis and is not cognitively normal, but is able to recognize people and interact and does much better on standard cognitive tests. The credit for her recovery goes to a psychiatrist, Sander Markx, who had seen the patient 20 years before, and upon learning that she was still institutionalized and unchanged order the workup that resulted in the diagnosis.

This is a remarkable case, but is not ultimately surprising. I had a similar case as a resident. A patient was admitted with worsening schizophrenia. He had severe schizophrenia for the last 20 years or so, mostly cared for at home by his family, but now was simply getting too difficult to give proper care. He was admitted to the psychiatry floor, and they consulted the neurology service almost as an afterthought, because the patient had been lost to follow up for so long. We had a low clinical suspicion that there was anything neurological going on, but recommended a CT scan of the brain and other workup, just to be thorough. The CT scan found a very large tumor pushing in on his frontal lobes. The tumor itself was outside the brain but inside the skull. Neurosurgery was consulted, the tumor was promptly removed, and within days the patient was almost back to his pre-schizophrenic baseline – essentially cured. That’s the kind of case you never forget.

To put such cases into clinical perspective it’s important to recognize that schizophrenia is a clinical diagnosis, meaning that it is based upon signs and symptoms, not any pathological findings on imaging or laboratory workup. There are markers and researchers are trying to understand it better as a brain disease, but for now the diagnosis is still mainly clinical. Part of the clinical diagnosis, however, is ruling out neurological pathology. This is a standard referral that we neurologists get from psychiatrists – rule out neurological disease. Only when that is done is the patient given a psychiatric diagnosis.

In fact, we can take a step back and ask the deeper question of what the difference is between psychiatric and neurological conditions. They all involve the brain and brain function. In reality, the line is fuzzy. From a practical point of view, psychiatrists specialize in disorders that involve changes to mood, behavior, and cognition, and further that are not due to any treatable underlying pathology. They still might get involved in the management of patients with mood or behavioral symptoms from known pathology, but then the psychiatric symptoms are considered secondary to the medical condition. They are not a primary psychiatric disorder. Basically they are the experts in diagnosing and treating these kinds of symptoms.

From a theoretical point of view, psychiatrists tend to deal with disorders that are a result of dysfunctional networks in the brain, or extreme environmental conditions or stress. PTSD is a good example – there is no pathology, but there is a disorder brought about by extreme emotional stress. But this division is not sharp, as many neurological conditions are also similarly functional (such as migraine headaches). There is a lot of overlap between psychiatry and neurology, which is why there is required cross training for both disciplines.

One way, therefore, to look at the case of April Burrell is that she had a schizophrenia-like syndrome secondary to autoimmune disease attacking her brain. Similarly, the patient I described above had a schizophrenia syndrome secondary to a tumor pushing on his brain. The notion of secondary causes of schizophrenia is not new or surprising. Also, one of the goals of medical research is to constantly nibble away at incurable syndromes, finding more and more potential causes to treat. Over time the workup to rule out treatable causes expands, as we discover new things to diagnose and treat. So this is just one more step in an established process, not a revelation.

It is also not new that autoimmune disease can cause psychiatric-looking brain syndromes. I have seen many of these patients myself. They can be tricky to diagnoses, because initial workup can be negative. Often, however, the symptoms progress until the underlying pathology is more apparent. There is also a good rule of thumb in neurology – when in doubt, give steroids. If you have a strange case of a patient with a combination of psychiatric symptoms, decreased mental status, and especially if they also have seizures (but not required), it is reasonable to give them a trial of intravenous steroids to see if this helps. Some of these patients have what we call limbic encephalitis, and sometimes the only way to confirm the diagnosis is with a treatment trial with steroids.

It’s also worth pointing out (a teaching point I emphasize for my students and residents) that the far frontal lobes of the brain are involved with higher cognitive function, but pathology here can be missed on a standard neurological exam. Patients may present with pure psychiatric symptoms, and not have any abnormal exam findings (or only very subtle findings) to suggest brain pathology. That is why imaging is standard for new presentations, even with an otherwise normal (or what we would call “non-focal” exam).

But there is also another lesson here I often emphasize to my students – do not get complacent. Once a patient has been evaluated, worked up, and then placed in long term care, it is easy to become complacent about them. But we need to remain forever curious, and to periodically reevaluate patients and think about them anew, especially in the light of recent advances. Has this patient bee worked up recently? Has there been any new discoveries since their last evaluation? Is it possible that something was missed in the past? We don’t have the resources to endlessly re-workup every patient, but there are at least questions we should ask. The case of April should remind us that it is possible for diagnoses to have been missed in the past, and that some primary or idiopathic diagnoses should forever have a question mark next to them. A diagnosis of exclusion is only as good as the exclusion – was it thorough enough, and is it up to date? It’s a good reminder, and hopefully will result in more doctors like Markx taking a second look at more patients like April.