Oct 02 2023

Tong Test for Artificial General Intelligence

Most readers are probably familiar with the Turing Test – a concept proposed by early computing expert Alan Turing in 1950, and originally called “The Imitation Game”. The original paper is enlightening to read. Turing was not trying to answer the question “can machines think”. He rejected this question as too vague, and instead substituted an operational question which has come to be known as the Turing Test. This involves an evaluator and two subjects who cannot see each other but communicate only by text. The evaluator knows that one of the two subjects is a machine and the other is a human, and they can ask whatever questions they like in order to determine which is which. A machine is considered to have passed the test if it fools a certain threshold of evaluators a percentage of the time.

Most readers are probably familiar with the Turing Test – a concept proposed by early computing expert Alan Turing in 1950, and originally called “The Imitation Game”. The original paper is enlightening to read. Turing was not trying to answer the question “can machines think”. He rejected this question as too vague, and instead substituted an operational question which has come to be known as the Turing Test. This involves an evaluator and two subjects who cannot see each other but communicate only by text. The evaluator knows that one of the two subjects is a machine and the other is a human, and they can ask whatever questions they like in order to determine which is which. A machine is considered to have passed the test if it fools a certain threshold of evaluators a percentage of the time.

But Turing did appear to believe that the Turing Test would be a reasonable test of whether or not a computer could think like a human. He systematically addresses a number of potential objections to this conclusion. For example, he quotes Professor Jefferson from a speech from 1949:

“Not until a machine can write a sonnet or compose a concerto because of thoughts and emotions felt, and not by the chance fall of symbols, could we agree that machine equals brain-that is, not only write it but know that it had written it.”

Turning then rejects this argument as solipsist – that we can only know that we ourselves are conscious because we are conscious. As an aside, I disagree with that. People can know that other people are conscious because we all have similar brains. But an artificial intelligence (AI) would be fundamentally different, and the question is – how is the AI creating its output? Turing gives as an example of how his test would be sufficient a sonnet writer defending the creative choices of their own sonnet:

What would Professor Jefferson say if the sonnet-writing machine was able to answer like this in the viva voce? I do not know whether he would regard the machine as “merely artificially signalling” these answers, but if the answers were as satisfactory and sustained as in the above passage I do not think he would describe it as “an easy contrivance.” This phrase is, I think, intended to cover such devices as the inclusion in the machine of a record of someone reading a sonnet, with appropriate switching to turn it on from time to time. In short then, I think that most of those who support the argument from consciousness could be persuaded to abandon it rather than be forced into the solipsist position. They will then probably be willing to accept our test.

Essentially Turing is arguing that a machine that sufficiently passes his test, by demonstrating real understanding of some material, would be sufficient to establish that it is “thinking” like a human – what we would now call artificial general intelligence (AGI). Seventy-three years later, however, I think that Turing has been proven wrong. Narrow AIs, those that work more through a “contrivance” of “artificial signaling” than through “machine equals brain”, have been able to perform in a way equal to Turing’s example. Large language models built upon transformer technology (ChatGPT) can write a sonnet and defend its choices. (I just did it. Do it yourself – arguably surpassing Turing’s example of what a non-thinking machine could not do.)

People are clever, and computer scientists have figured out how to leverage the power of narrow AI to accomplish things that in the past computer scientists like Turing naively believed required a general AI (arguably beginning by beating humans at chess). We need a new test for AGI. This is why computer scientists have proposed what they are calling the Tong Test, not after a person but after the Chinese word for “general”.

The paper does not lay out an operational test, exactly, but proposes features of AGI that would need to be demonstrated in order to consider it a genuine sentient entity. The paper is a bit dense, but here are the main points. First they propose that an AGI must be, “rooted in dynamic embodied physical and social interactions (DEPSI)”. Further they propose five critical features of a DEPSI AGI.

First it must demonstrate an infinite task-generating system. A true AGI must be adaptable to a potentially infinite task space, not limited by a finite (even if huge) number of tasks it can complete. The idea here is that an AGI must have an understanding at some level of the task at hand. They can go from a general command – clean this space – to generate specific tasks adapted to whatever conditions it finds in the space, including generating subtasks. It must understand what “clean” means, and figure out how to achieve that goal, without being instructed or trained on what steps to take.

A Roomba, by contrast, does not know that it is cleaning. It’s just following an algorithm. That is what makes AGI systems “brittle” – they break down when they encounter novel obstacles because they don’t have any deeper understanding of what they are doing. As an example the authors say – would would the AI do if it encounters a $100 bill? Would it throw it away as trash, or recognize it as having value and set it aside?

Second, an AGI should have a value-system, which the authors break down to a”…U–V dual system. The U-system describes the agent’s understanding of extrinsic physical or social rules, while the V-system comprises the agent’s intrinsic values, which are defined as a set of value functions upon which the self-driven behaviors of the agent are built.” This relates to the generation of infinite tasks – the AGI has underlying values or rules from which it can generate infinite specific tasks. It may know, for example, that human life has value and self-generate tasks to protect human life.

The authors, therefore, define a third criterion as “self-generated tasks”. These first three features can be summarized, therefore, as a true AGI system should have a system of values, both internal and external, by which it can self-generate a potentially infinite number of specific tasks.

In addition, however, it has to understand something about how the universe works, and this starts with causal understanding. It has to have a basic understanding of cause and effect, and be able to leverage this understanding to problem-solve. For example, if it needs to get something off a high shelf it cannot reach, it would understand that if it uses a long stick to push it off, gravity will cause it to fall into its hands.

This connects to the final feature – embodiment. A DEPSI AGI needs to be embodied in some way, which can be physical or virtual. It needs to exist in the world as a discrete entity that can interact with other things in the world through a chain of cause and effect.

The authors propose that an AGI that can demonstrate these five features must be a true AGI – a human-like sentient entity. Or at least, they are designing a specific environment in which these abilities and traits can be tested. I like the direction in which they are going. They are proposing interconnected abilities that demonstrate a deeper understanding of values and causation. Certainly a system that functions in such a way is a lot closer to an AGI than a brute-force large language model, for example. ChatGPT has no understanding or values, but it mimics a system that does because it is a language model, and we use language as a marker for thinking. So it’s good at creating the illusion of thinking, but it’s just modeling language.

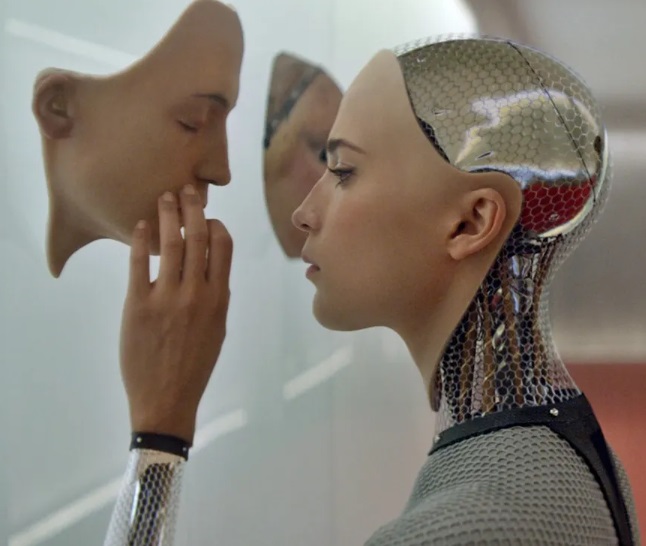

I have to say, though, I like the test proposed in the movie Ex Machina better. In the movie Nathan Bateman, a tech trillionaire who has developed an AGI robot named AVA, brings in programmer Caleb Smith to interact with AVA to determine if he thinks she is truly conscious. In reality, Bateman is conducting a deeper experiment to see if AVA will be able to manipulate Caleb in order to secure her freedom. Ava would need to have a theory of mind (that other people have thoughts and feelings), and understand the rules of human social interaction, as well as cause and effect problem solving. She would then need to devise a plan to manipulate Caleb into setting her free. Ava would have to generate all of the five features above, and then some.

In fact, I would explicitly add to the Tong Test demonstration of a theory of mind, and would argue that this is the most convincing feature of all that an AI is truly a conscious AGI. What better way to demonstrate that a system has consciousness than demonstrating understanding that other thinking beings also have consciousness and feelings. That understanding comes from projecting one’s own consciousness onto others. lf

We still have the problem of a really good narrow AI mimic – if it were programmed to mimic human language and behavior, we might falsely infer a theory of mind from the output. This is why the Tong feature are still important – things like infinite self-generated tasks based on a deeper level understanding of values and cause and effect are necessary. But also ultimately we need to know something about how the system works. We know ChatGPT is just a really good chat bot, pretrained on lots of human language. But if theory-of-mind behavior emerged from an AGI without being programmed and trained to mimic such behavior, that would be compelling.

It’s a really interesting thought experiment – how could we know an AGI was truly conscious? Some combination or iteration of the Tong Test with the Ex Machina test would certainly be compelling. But ultimately I also think we need to know something about how the system operates. Because I think any such test can be passed if a narrow AI were powerful enough, sophisticated enough, and trained on enough data.