Apr 05 2019

The Color of Vowels

What is the color, if you had to choose, of the “oo” sound in “boot”? What about the “ay” sound in “say”?

What is the color, if you had to choose, of the “oo” sound in “boot”? What about the “ay” sound in “say”?

Researchers asked 1,000 participants this question, 200 of which have synesthesia – a condition in which different sensory and cognitive modalities blend into each other. Interestingly, 70% of non-synesthetes still had a structured answer to these questions. They had a mental map of what vowel sounds had which colors.

Synesthesia is a fascinating phenomenon, that is also a good reminder that our brains are just squishy machines, and they have quirky flaws like all machines. Brain function is mostly a result of networks of neurons firing together. There are various biological mechanisms that control the firing of neurons, so that they participate in networks but these electrical signals do not spread randomly through the brain (that’s basically what a seizure is).

These networks are horrifically complex, and interact with each other is complex ways to create neurological function. There are all sorts of variations of this brain wiring that can produce all the variation we see in people, including some that we would consider disorders or pathological.

Synesthesia is more of a condition than a disorder because it does not necessarily cause any demonstrable harm, and may even be an advantage in certain ways. Synesthetes have their brain networks crosses in unusual ways, so that they smell sound, see odors, or hear colors. They may also assign sensations to abstract concepts. Numbers may have a color, texture, or contour, for example. This is not imagination – they really perceive these things.

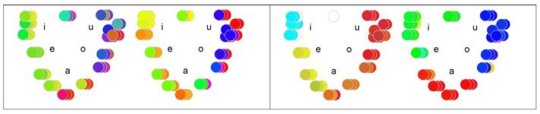

In the current study the authors focused on a common abstract form of synesthesia in which vowel sounds are perceived as having color. Unsurprisingly, these types of synesthetes produced a consistent and strongly correlated pattern of associating colors and vowels.

More interesting is that many non-synesthetes did also, although to a lesser degree. This may be an entirely different phenomenon from synesthesia itself, not an actual perception of color on any level, but a purely cognitive association. Other studies have shown similar associations – for example that people tend to associate a higher pitch with a lighter color.

The associations may also have to do with language. This study was done entirely with Dutch speaking participants, and of course it would be interesting to replicate it in other languages. It’s possible, for example, that we associate certain vowels with certain colors because of the cognitive associations with words that use those vowels.

Initially linguists believed that there was no association between word sounds and meanings. Different languages have completely different words for the same thing, for example. But more recent statistical analyses have shown significant correlations between types of sounds and word meaning, not a random distribution. A 2016 study looking at 2/3 of the languages on Earth found these correlations.

Words for “nose” tend to contain an “n”, for example. Words for “small” tend to contain an “i” (as in “tiny” in English).

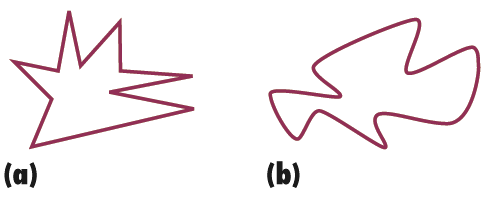

There is also the kiki-baoba test. In different cultures tested, 95% of participants assigned the same name (“kiki” or “baoba”) to the two shapes shown (kiki to a). This one seems obvious, because “kiki” is more sharp sounding, and “baoba” is more rounded. But this intuition is actually the point.

There is also the kiki-baoba test. In different cultures tested, 95% of participants assigned the same name (“kiki” or “baoba”) to the two shapes shown (kiki to a). This one seems obvious, because “kiki” is more sharp sounding, and “baoba” is more rounded. But this intuition is actually the point.

The 2016 study found similar consistent patterns, but also found that in some cultures the intuitive correlations were different. For example, in Western speakers high pitched sounds were associated with being small, while low pitched sounds were associated with being large. This makes sense because bigger animals tend to make lower-pitched noises. There is an actual physical relationship between size and pitch.

But in China this association was reverse, with higher pitch associated with being larger. The researchers speculate that this is because is Chinese theater, high pitch is often used to signify power.

In other study students were asked to make up entirely new words for common concepts, like big or small. Other students were then asked to guess what the words meant among the offered choices based entirely on what they sound like. They were very good at guessing which words went with which concepts – better than random guessing.

It seems, therefore, that we do have an intuitive cognitive map that relates word sounds to certain concepts. These intuitions may be partly universal, partly a response to the physical world, and partly cultural.

The question is – is it also partly neurological. Does the typical wiring of the human brain result in some synesthesia-like correlations, even if we don’t consciously perceive them? Are synesthetes just people who can consciously perceive what for everyone else is subconscious? I don’t think we know the answer to this yet. Also, the answer may be both – some synesthesia may be due to just an increased strength of correlation, rising up to the conscious level, while others may be due to novel networking not typically present in most people.

Research into our subconscious neurological intuitions is fascinating, and is likely to provide interesting and useful insights into how our brains work.