Mar 11 2024

Mach Effect Thrusters Fail

When thinking about potential future technology, one way to divide possible future tech is into probable and speculative. Probable future technology involves extrapolating existing technology into the future, such as imaging what advanced computers might be like. This category also includes technology that we know is possible, we just haven’t mastered it yet, like fusion power. For these technologies the question is more when than if.

When thinking about potential future technology, one way to divide possible future tech is into probable and speculative. Probable future technology involves extrapolating existing technology into the future, such as imaging what advanced computers might be like. This category also includes technology that we know is possible, we just haven’t mastered it yet, like fusion power. For these technologies the question is more when than if.

Speculative technology, however, may or may not even be possible within the laws of physics. Such technology is usually highly disruptive, seems magical in nature, but would be incredibly useful if it existed. Common technologies in this group include faster than light travel or communication, time travel, zero-point energy, cold fusion, anti-gravity, and propellantless thrust. I tend to think of these as science fiction technologies, not just speculative. The big question for these phenomena is how confident are we that they are impossible within the laws of physics. They would all be awesome if they existed (well, maybe not time travel – that one is tricky), but I am not holding my breath for any of them. If I had to bet, I would say none of these exist.

That last one, propellantless thrust, does not usually get as much attention as the other items on the list. The technology is rarely discussed explicitly in science fiction, but often it is portrayed and just taken for granted. Star Trek’s “impulse drive”, for example, seems to lack any propellant. Any ship that zips into orbit like the Millennium Falcon likely is also using some combination of anti-gravity and propellantless thrust. It certainly doesn’t have large fuel tanks or display any exhaust similar to a modern rocket.

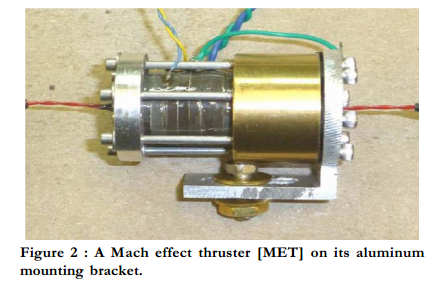

In recent years NASA has tested two speculative technologies that claim to be able to produce thrust without propellant – the EM drive and the Mach Effect thruster (MET). For some reason the EM drive received more media attention (including from me), but the MET was actually the more interesting claim. All existing forms of internal thrust involve throwing something out the back end of the ship. The conservation of momentum means that there will be an equal and opposite reaction, and the ship will be thrust in the opposite direction. This is your basic rocket. We can get more efficient by accelerating the propellant to higher and higher velocity, so that you get maximal thrust from each atom or propellant your ship carries, but there is no escape from the basic physics. Ion drives are perhaps the most efficient thrusters we have, because they accelerate charged particles to relativistic speeds, but they produce very little thrust. So they are good for moving ships around in space but cannot get a ship off the surface of the Earth.

The problem with propellant is the rocket equation – you need to carry enough fuel to accelerate the fuel, and more fuel for that fuel, etc. It means that in order to go anywhere interesting very fast you need to carry massive amounts of fuel. The rocket equation also sets a lot of serious limits on space travel, in terms of how fast and far we can go, how much we can lift into orbit, and even if it is possible to escape from a strong gravity well (chemical rockets have a limit of about 1.5 g).

If it were possible to create thrust directly from energy without the need for propellant, a so-called propellantless or reactionless drive, that would free us from the rocket equation. This would make space travel much easier, and even make interstellar travel possible. We can accomplish a similar result by using external thrust, for example with a light sail. The thrust can come from a powerful stationary laser that pushes against the light sail of a spacecraft. This may, in fact, be our best bet for long distance space travel. But this approach has limits as well, and having an onboard source of thrust is extremely useful.

The problem with propellantless drives is that they probably violate the laws of physics, specifically the conservation of momentum. Again, the real question is – how confident are we that such a drive is impossible? Saying we don’t know how it could work is not the same as saying we know it can’t work. The EM drive is alleged to work using microwaves in a specially designed cone so that as they bounce around they push slightly more against one side than the other, generating a small amount of net thrust (yes, this is a simplification, but that’s the basic idea). It was never a very compelling idea, but early tests did show some possible net thrust, although very tiny.

The fact that the thrust was extremely tiny, to me, was very telling. The problem with very small effect sizes is that it’s really easy for them to be errors, or to have extraneous sources. This is a pattern we frequently see with speculative technologies, from cold fusion to free-energy machines. The effect is always super tiny, with the claim that the technology just needs to be “scaled up”. Of course, the scaling up never happens, because the tiny effect was a tiny error. So this is always a huge red flag to me, one that has proven extremely predictive.

And in fact when NASA tested the EM drive under rigorous testing conditions, they could not detect any anomalous thrust. With new technology there are two basic types of studies we can do to explore them. One is to explore the potential underlying physics or phenomena – how could such technology work. The other is to simply test whether or not the technology works, regardless of how. Ideally both of these types of evidence will align. There is often debate about which type of evidence is more important, with many proponents arguing that the only thing that matters is if the technology works. But the problem here is that often the evidence is low-grade or ambiguous, and we need the mechanistic research to put it into context.

But I do agree, at the end of the day, if you have sufficiently high level rigorous evidence that the phenomenon either exists or doesn’t exist, that would trump whether or not we currently know the mechanism or the underlying physics. That is what NASA was trying to do – a highly rigorous experiment to simply answer the question – is there anomalous thrust. Their answer was no.

The same is true of the MET. The theory behind the MET is different, and is based on some speculative physics. The idea stems from a question in physics for which we do not currently have a good answer – what determines inertial frames of reference. For example, if you have a bucket of water in deep intergalactic space (sealed at the top to contain the water), and you spin it, centrifugal force will cause the water to climb up the sides of the buck. But how can we prove physically that the bucket is spinning and the universe is not spinning around it. In other words – what is the frame of reference. We might intuitive feel like it makes more sense that the bucket is spinning, but how do we prove that with physics and math? What theory determines the frame of reference?

One speculative theory is that the inertial frame of reference is determined by the total mass energy of the universe, it derives from an interaction between an object and the rest of the universe. If this is the case then perhaps you can change that inertia by pushing against the rest of the universe, without expelling propellant. If this is all true, then the MET could theoretically work. This seems to be one step above the EM drive in that the EM drive likely violates the known laws of physics, while the MET is based on unknown laws.

Well, NASA tested the MET also and – no anomalous thrust. Proponents, of course, could always argue that the experimental setup was not sensitive enough. But at some point, teeny tiny becomes practically indistinguishable from zero.

It seems that we do not have a propellantless drive in our future, which is too bad. But the idea is so compelling that I also doubt we have seen the end of such claims, as with perpetual motion machines and free energy. There are already other claims, such as the quantum drive. There are likely to be more. What I typically say to proponents is this – scale it up first, then come talk to me. Since “scaling up” tends to be the death of all of these claims, that’s a good filter.