Mar

04

2024

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

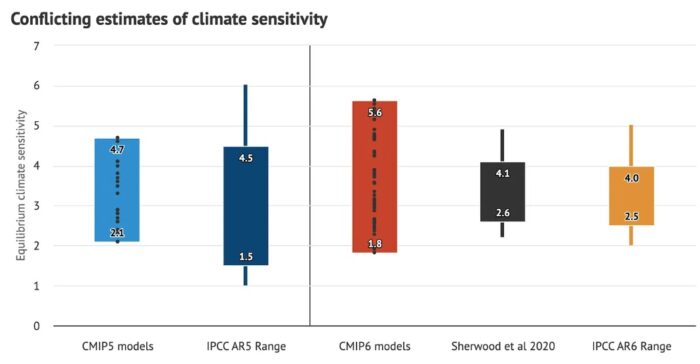

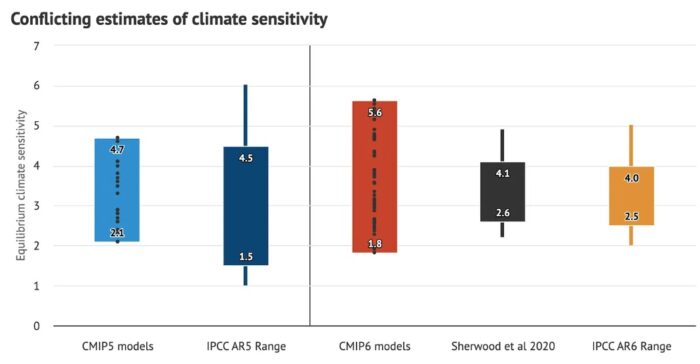

First let me review the relevant background. ECS is a measure of how much climate warming will occur as CO2 concentration in the atmosphere increases, specifically the temperature rise in degrees Celsius with a doubling of CO2 (from pre-industrial levels). This number of of keen significance to the climate change problem, as it essentially tells us how much and how fast the climate will warm as we continue to pump CO2 into the atmosphere. There are other variables as well, such as other greenhouse gases and multiple feedback mechanisms, making climate models very complex, but the ECS is certainly a very important variable in these models.

There are multiple lines of evidence for deriving ECS, such as modeling the climate with all variables and seeing what the ECS would have to be in order for the model to match reality – the actual warming we have been experiencing. Therefore our estimate of ECS depends heavily on how good our climate models are. Climate scientists use a statistical method to determine the likely range of climate sensitivity. They take all the studies estimating ECS, creating a range of results, and then determine the 90% confidence range – it is 90% likely, given all the results, that ECS is between 2-5 C.

Continue Reading »

Feb

27

2024

Amid much controversy, the Alabama State Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos are children. They did not support their decision with compelling logic, with cited precedence (their decision is literally unprecedented), with practical considerations, or with sound ethical judgement. They essentially referenced god. It was a pretty naked religious justification.

Amid much controversy, the Alabama State Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos are children. They did not support their decision with compelling logic, with cited precedence (their decision is literally unprecedented), with practical considerations, or with sound ethical judgement. They essentially referenced god. It was a pretty naked religious justification.

The relevant politics have been hashed out by many others. What I want to weigh in on is the relevant logic. Two years ago I wrote about the question of when a fetus becomes a person. I laid out the core question here – when does a clump of cells become a person? Standard rhetoric in the anti-abortion community is to frame the question differently, claiming that from the point of fertilization we have human life. But from a legal, moral, and ethical perspective, that is not the relevant question. My colon is human life, but it’s not a person. Similarly, a frozen clump of cells is not a child.

This point inevitably leads to the rejoinder that those cells have the potential to become a person. But the potential to become a thing is not the same same as being a thing. If allowed to develop those cells have the potential to become a person – but they are not a person. This would be analogous to pointing to a stand of trees and claiming it is a house. Well, the wood in those trees has the potential to become a house. It has to go through a process, and at some point you have a house.

That analogy, however, breaks down when you consider that the trees will not become a house on their own. An implanted embryo will become a child (if all goes well) unless you do something to stop it. True but irrelevant to the point. The embryo is still not a person. The fact that the process to become a person is an internal rather than external one does not matter. Also, the Alabama Supreme Court is extending the usual argument beyond this point – those frozen embryos will not become children on their own either. They would need to go through a deliberate, external, artificial process in order to have the full potential to develop into a person. In fact, they would not exist without such a process.

Continue Reading »

Feb

06

2024

Have you ever been in a discussion where the person with whom you disagree dismisses your position because you got some tiny detail wrong or didn’t know the tiny detail? This is a common debating technique. For example, opponents of gun safety regulations will often use the relative ignorance of proponents regarding gun culture and technical details about guns to argue that they therefore don’t know what they are talking about and their position is invalid. But, at the same time, GMO opponents will often base their arguments on a misunderstanding of the science of genetics and genetic engineering.

Have you ever been in a discussion where the person with whom you disagree dismisses your position because you got some tiny detail wrong or didn’t know the tiny detail? This is a common debating technique. For example, opponents of gun safety regulations will often use the relative ignorance of proponents regarding gun culture and technical details about guns to argue that they therefore don’t know what they are talking about and their position is invalid. But, at the same time, GMO opponents will often base their arguments on a misunderstanding of the science of genetics and genetic engineering.

Dismissing an argument because of an irrelevant detail is a form of informal logical fallacy. Someone can be mistaken about a detail while still being correct about a more general conclusion. You don’t have to understand the physics of the photoelectric effect to conclude that solar power is a useful form of green energy.

There are also some details that are not irrelevant, but may not change an ultimate conclusion. If someone thinks that industrial release of CO2 is driving climate change, but does not understand the scientific literature on climate sensitivity, that doesn’t make them wrong. But understanding climate sensitivity is important to the climate change debate, it just happens to align with what proponents of anthropogenic global warming are concluding. In this case you need to understand what climate sensitivity is, and what the science says about it, in order to understand and counter some common arguments deniers use to argue against the science of climate change.

What these few examples show is a general feature of the informal logical fallacies – they are context dependent. Just because you can frame someone’s position as a logical fallacy does not make their argument wrong (thinking this is the case is the fallacy fallacy). What logical fallacy is using details to dismissing the bigger picture? I have heard this referred to as a “Reverse Gish Gallop”. I’m don’t use this term because I don’t think it captures the essence of the fallacy. I have used the term “weaponized pedantry” before and I think that is better.

Continue Reading »

Feb

02

2024

Homer: Not a bear in sight. The Bear Patrol must be working like a charm.

Homer: Not a bear in sight. The Bear Patrol must be working like a charm.

Lisa: That’s specious reasoning, Dad.

Homer: Thank you, dear.

Lisa: By your logic I could claim that this rock keeps tigers away.

Homer: Oh, how does it work?

Lisa: It doesn’t work.

Homer: Uh-huh.

Lisa: It’s just a stupid rock.

Homer: Uh-huh.

Lisa: But I don’t see any tigers around, do you?

[Homer thinks of this, then pulls out some money]

Homer: Lisa, I want to buy your rock.

[Lisa refuses at first, then takes the exchange]

This memorable exchange from The Simpsons is one of the reasons the fictional character, Lisa Simpson, is a bit of a skeptical icon. From time to time on the show she does a descent job of defending science and reason, even toting a copy of “Jr. Skeptic” magazine (which was fictional at the time then created as a companion to Skeptic magazine).

What the exchange highlights is that it can be difficult to demonstrate (let alone “prove”) that a preventive measure has worked. This is because we cannot know for sure what the alternate history or counterfactual would have been. If I take a measure to prevent contracting COVID and then I don’t get COVID, did the measure work, or was I not going to get COVID anyway? Historically the time this happened on a big scale was Y2K – this was a computer glitch set to go off when the year changed to 2000. Most computer code only encoded the year as two digits, assuming the first two digits were 19, so 1995 was encoded as 95. So when the year changed to 2000, computers around the world would think it was 1900 and chaos would ensue. Between $300 billion and $500 billion were spent world wide to fix this bug by upgrading millions of lines of code to a four digit year stamp.

Did it work? Well, the predicted disasters did not happen, so from that perspective it did. But we can’t know for sure what would have happened if we did not fix the code. This has lead to speculation and even criticism about wasting all that time and money fixing a non-problem. There is good reason to think that the preventive measures worked, however.

At the other end of the spectrum, often doomsday cults, predicting that the world will end in some way on a specific date, have to deal with the day after. One strategy is to say that the faith of the group prevented doomsday (the tiger-rock strategy). They can now celebrate and start recruiting to prevent the next doomsday.

Continue Reading »

Jan

08

2024

Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters.

Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters.

We can start with an example that might seem like a simple category – what is a planet? Of course, any science nerd knows how contentious the definition of a planet can be, which is why it is a good example. Astronomers first defined them as wandering stars – the points of light that were not fixed but seemed to wonder throughout the sky. There was something different about them. This is often how categories begin – we observe a phenomenon we cannot explain and so the phenomenon is the category. This is very common in medicine. We observe a set of signs and symptoms that seem to cluster together, and we give it a label. But once we had a more evolved idea about the structure of the universe, and we knew that there are stars and stars have lots of stuff orbiting around them, we needed a clean way to divide all that stuff into different categories. One of those categories is “planet”. But how do we define planet in an objective, intuitive, and scientifically useful way?

This is where the concept of “defining characteristic” comes in. A defining characteristic is, “A property held by all members of a class of object that is so distinctive that it is sufficient to determine membership in that class. A property that defines that which possesses it.” But not all categories have a clear defining characteristic, and for many categories a single characteristic will never suffice. Scientists can and do argue about which characteristics to include as defining, which are more important, and how to police the boundaries of that characteristic.

Continue Reading »

Dec

15

2023

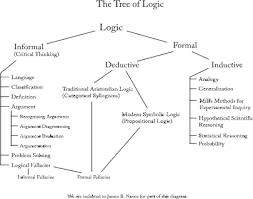

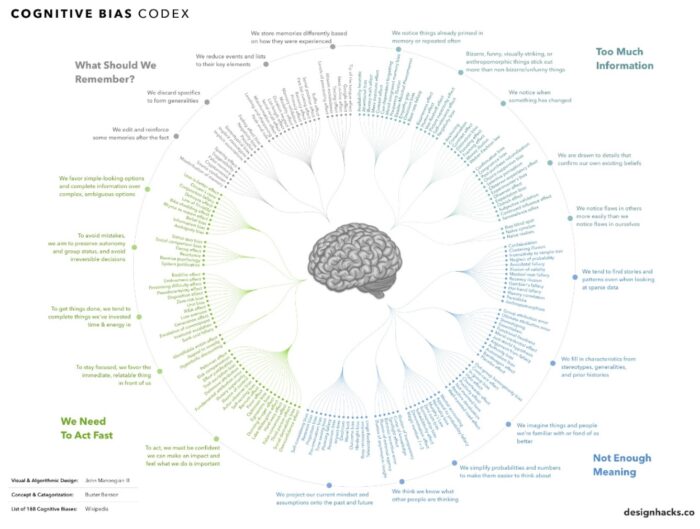

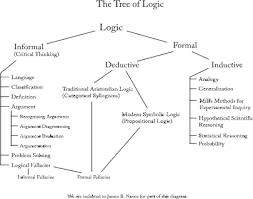

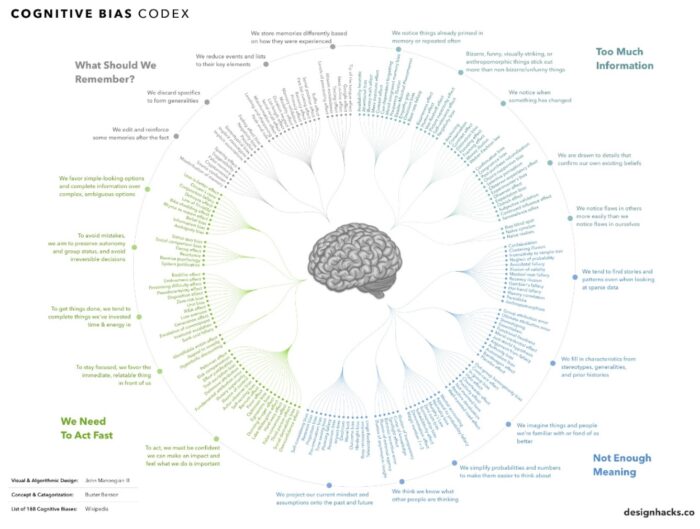

I like to think deeply about informal logical fallacies. I write about them a lot, and even have an occasional segment of the SGU dedicated to them. They are a great way to crystalize our thinking about the many ways in which logic can go wrong. Formal logic deals with arguments that are always true, by there very construction. If A=B and B=C then A=C, is always true. Informal logical fallacies, on the other hand, are context dependent. They are a great way to police the sharpness of arguments, but they require a lot of context-dependent judgement.

I like to think deeply about informal logical fallacies. I write about them a lot, and even have an occasional segment of the SGU dedicated to them. They are a great way to crystalize our thinking about the many ways in which logic can go wrong. Formal logic deals with arguments that are always true, by there very construction. If A=B and B=C then A=C, is always true. Informal logical fallacies, on the other hand, are context dependent. They are a great way to police the sharpness of arguments, but they require a lot of context-dependent judgement.

For example, the Argument from Authority fallacy recognizes that a fact claim is not necessarily true just because an authority states it, but it could be true. And recognizing meaningful authority is useful, it’s just not absolute. It’s more of a probability and the weight of opinion. But authority itself does not render a claim true or false. The same is true of the Argument ad Absurdum, or the Slippery Slope fallacy – they are about taking an argument to an unjustified extreme. But what’s “extreme”? This subjectivity might cause one to think that they are therefore not legitimate logical fallacies at all, but that’s just the False Continuum logical fallacy – the notion that if there is not a sharp demarcation line somewhere along a spectrum, then we can ignore or deny the extremes of the spectrum.

I recently received the following question about a potential informal fallacy:

I’ve noticed this more and more with politics. Party A proposes a ludicrous solution to an issue. Party B objects to the policy. Party A then accuse Party B of being in favour of the issue. It’s happening in the immigration debate in the UK where the government are trying to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda (current capacity around 200 per year) in order to solve our “record levels of immigration” (over 700,000 this year of which less than 50,000 are asylum seekers). When you object to the policy you are accused of being in support of unlimited immigration.

This feels like something wider, that may even be a logical fallacy, but I’ve not been able to locate anything describing it. I can imagine it comes up in Skepticisim relatively often.

Continue Reading »

May

16

2023

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure).

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure).

I also get e-mails, and my recent article on ESP research attracted a number of angry individuals who wanted to excoriate my closed minded “scientism”. I think people care so much about ESP and other psi and paranormal phenomena because it gets at the heart of their beliefs about reality – do we live in a purely naturalistic and mechanistic world, or do we live in a world where the supernatural exists? Further, in my experience while many people are happy to praise the virtue of faith (believing without knowing) in reality they desperately want there to be objective evidence for their beliefs. Meanwhile, I think it’s fair to say that a dedicated naturalist would find it “disturbing” (if I can paraphrase Darth Vader) if there really were convincing evidence that contradicts naturalism. Both sides have an out, as it were. Believers in a supernatural universe can always say that the supernatural by definition is not provable by science. One can only have faith. This is a rationalization that has the virtue of being true, if properly formulated and utilized. Naturalists can also say that if you have actual scientific evidence of an alleged paranormal phenomenon, then by definition it’s not paranormal. It just reflects a deeper reality and points in the direction of new science. Yeah!

Regardless of what you believe deep down about the ultimate nature of reality (and honestly, I couldn’t care less, as long as you don’t think you have the right to impose that view on others), the science is the science. Science follows methodological naturalism, and is agnostic toward the supernatural question. It operates within a framework of naturalism, but recognizes this is a construct, and does not require philosophical naturalism. So you can have your faith, just don’t mess with science.

Continue Reading »

Apr

17

2023

I first wrote about the Theranos scandal in 2016, and I guess it should not be surprising that it took 7 years to follow this story through to the end. Elizabeth Holmes, founder of the company Theranos, was convicted of defrauding investors and sentenced to 11 years in prison. She will be going to prison even while her appeal is pending, because she failed to convince a judge that she is likely to win on appeal.

I first wrote about the Theranos scandal in 2016, and I guess it should not be surprising that it took 7 years to follow this story through to the end. Elizabeth Holmes, founder of the company Theranos, was convicted of defrauding investors and sentenced to 11 years in prison. She will be going to prison even while her appeal is pending, because she failed to convince a judge that she is likely to win on appeal.

I think her conviction and sentencing is a healthy development, and I hope it has an impact on the industry and broader culture. To quickly summarize, Holmes began a startup called Theranos which claimed to be able to perform 30 common medical laboratory tests on a single drop of blood and in a single day. So instead of collecting multiple vials of blood, with test results coming back over the course of a week, only a finger stick and drop of blood would be necessary (like people with diabetes do to test their blood sugar).

The basic idea is a good one, and also fairly obvious. Being able to determine reliable blood-testing results with a smaller sample, and being able to run multiple tests at a time, and very quickly, have obvious medical advantages. Patients, for example, who have prolonged hospital stays can actually get anemic from repeated blood draws. At some point testing has to be limited. Repeated blood sticks can also take its toll. For outpatient testing, rather than going to a lab, you could get a testing kit, provide a drop of blood, and then send it in.

The problem was that Holmes was apparently starting with a problem to be solved rather than a technology. We can think of technological development as happening in one of two primary ways. We may start with a problem and then search for a solution. Or we can start with a technology and look for applications. Both approaches have their pitfalls. The sweet spot is when both pathways meet in the middle – a new technology solves a clear problem.

Continue Reading »

Apr

03

2023

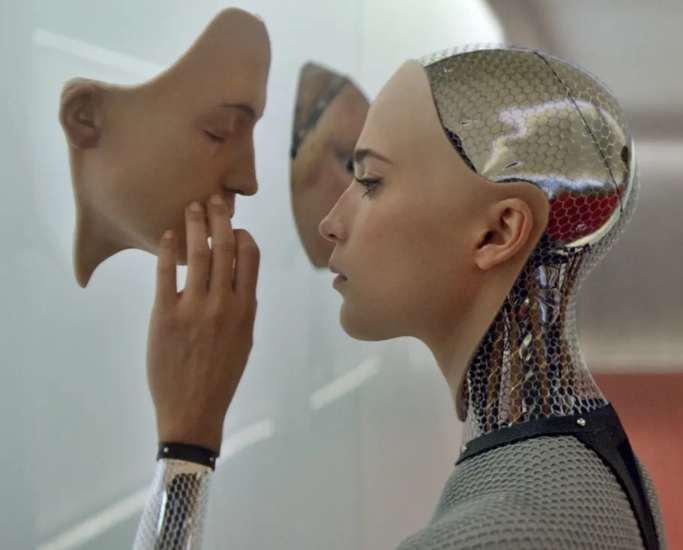

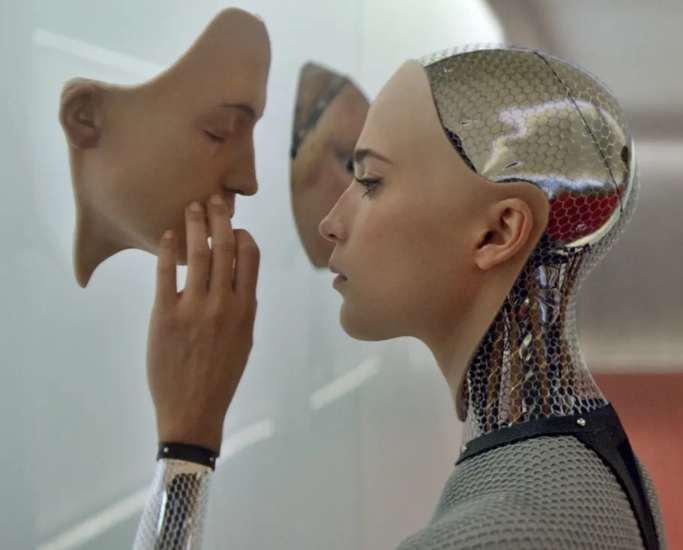

On the SGU this week we interviewed Blake Lemoine, the ex-Google employee who believes that Google’s LaMDA may be sentient, based on his interactions with it. This was a fascinating discussion, and even though I think we did a pretty deep dive in the time we had, it also felt like we were just scratching the surface of the complex topic. I want to summarize the topic here, give the reasons I don’t agree with Blake, and add some further analysis.

On the SGU this week we interviewed Blake Lemoine, the ex-Google employee who believes that Google’s LaMDA may be sentient, based on his interactions with it. This was a fascinating discussion, and even though I think we did a pretty deep dive in the time we had, it also felt like we were just scratching the surface of the complex topic. I want to summarize the topic here, give the reasons I don’t agree with Blake, and add some further analysis.

First, let’s define some terms. Intelligence is essentially the ability to know and process information, often in the context of adapting one’s responses to that information. A calculator, therefore, displays a type of intelligence. Sapience is deeper, implying understanding, perspective, insight, and wisdom. Sentience is the subjective experience of one’s existence, the ability to feel. And consciousness is the ability to be awake, to receive and process input and generate output, and to have some level of control over that process. Consciousness implies spontaneous internal mental activity, not just reactive.

These concepts are a bit fuzzy, they overlap and interact with each other, and we don’t really understand them fully phenomenologically, which is part of the problem of talking about whether or not something is sentient. But that doesn’t mean that they are meaningless concepts. There is clearly something going on in a human brain that is not going on in a calculator. Even if we consider a supercomputer with the processing power of a human brain, able to run complex simulations and other applications – I don’t think there is a serious argument to be made that it is sentient. It is not experiencing its own existence. It does not have feelings or emotions.

The question at hand is this – how do we know if something that displays intelligent behavior also is sentient? The problem is that sentience, by definition, is a subject experience. I know that I am sentient because of my own experience. But how do I know that any other living human being is also sentient?

Continue Reading »

Mar

21

2023

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

As is often the case, an optimal approach likely combines both strategies, trying to leverage the advantages of each. Therefore we often have disease headers with subtypes below to capture more detail. But even there the debate does not end – how far do we go splitting out subtypes of subtypes?

The debate also happens when we try to categorize ideas, not just things. Logical fallacies are a great example. You may hear of very specific logical fallacies, such as the “argument ad Hitlerum”, which is an attempt to refute an argument by tying it somehow to something Hitler did, said, or believed. But really this is just a specific instance of a “poisoning the well” logical fallacy. Does it really deserve its own name? But it’s so common it may be worth pointing out as a specific case. In my opinion, whatever system is most useful is the one we should use, and in many cases that’s the one that facilitates understanding. Knowing how different logical fallacies are related helps us truly understand them, rather than just memorize them.

A recent paper enters the “lumper vs splitter” fray with respect to cognitive biases. They do not frame their proposal in these terms, but it’s the same idea. The paper is – Toward Parsimony in Bias Research: A Proposed Common Framework of Belief-Consistent Information Processing for a Set of Biases. The idea of parsimony is to use to be economical or frugal, which often is used to apply to money but also applies to ideas and labels. They are saying that we should attempt to lump different specific cognitive biases into categories that represent underlying unifying cognitive processes.

Continue Reading »

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

Amid much controversy, the Alabama State Supreme Court ruled that

Amid much controversy, the Alabama State Supreme Court ruled that  Have you ever been in a discussion where the person with whom you disagree dismisses your position because you got some tiny detail wrong or didn’t know the tiny detail? This is a common debating technique. For example, opponents of gun safety regulations will often use the relative ignorance of proponents regarding gun culture and technical details about guns to argue that they therefore don’t know what they are talking about and their position is invalid. But, at the same time, GMO opponents will often base their arguments on a misunderstanding of the science of genetics and genetic engineering.

Have you ever been in a discussion where the person with whom you disagree dismisses your position because you got some tiny detail wrong or didn’t know the tiny detail? This is a common debating technique. For example, opponents of gun safety regulations will often use the relative ignorance of proponents regarding gun culture and technical details about guns to argue that they therefore don’t know what they are talking about and their position is invalid. But, at the same time, GMO opponents will often base their arguments on a misunderstanding of the science of genetics and genetic engineering. Homer: Not a bear in sight. The Bear Patrol must be working like a charm.

Homer: Not a bear in sight. The Bear Patrol must be working like a charm. Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters.

Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters. I like to think deeply about

I like to think deeply about  I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure).

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure). I first wrote about the

I first wrote about the  On

On  Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.