Oct 18 2016

The Hawthorne Effect Revisited

It’s always more complicated than you think. If there is one overall lesson I learned after 20 years as a science communicator, that is it. There is a general bias toward oversimplification, which to some extent is an adaptive behavior. The universe is massive and complicated, and it would be a fool’s errand to try to understand every aspect of it down to the tiniest level of detail. We tend to understand the world through distilled narratives, simple stories that approximate reality (whether we know it or not or whether we intend to or not).

Those distilled narratives can be very useful, as long as you understand they are simplified approximations and don’t confuse them with a full and complete description of reality. Different levels of expertise can partly be defined as the complexity of the models of reality that you use. It is also interesting to think about what is the optimal level of complexity for your own purposes. I try to take a deliberate practical approach – how much complexity do I need to know?

The Hawthorne Effect

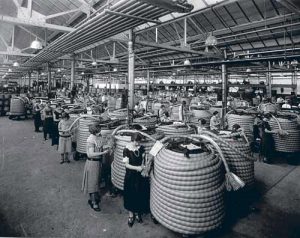

The distilled narrative of what is the Hawthorne Effect is this – the act of observing people’s behavior changes that behavior. The name derives from experiments conducted between 1924 and 1933 in Western Electric’s factory at Hawthorne, a suburb of Chicago. The experimenters made various changes to the working environment, like changing light levels, and noticed that regardless of the change, performance increased. If they increased light levels, performance increased. If they decreased light levels, performance increased. They eventually concluded that observing the workers was leading to the performance increase, and the actual change in working conditions was irrelevant. This is now referred to as an observer effect, but also the term Hawthorn Effect was coined in 1953 by psychologist J.R.P. French.

For most people, just understanding that one paragraph is a nice bit of knowledge, and is probably all they are going to remember long term. But of course – it’s more complicated than that. Science communicators often try to take the one-paragraph common knowledge to one-essay more thorough and nuanced knowledge, the level of a science enthusiast or, in this case, scientific skeptic. But of course, there are deeper levels still, representing various levels of actual expertise. The trick is to be essentially correct at each level of approximation.

The problem is that most one-paragraph summaries in the public consciousness are not essentially correct. Sometimes more detail and nuance is needed to get to an acceptable level of correctness. Knowing where that level resides is also part of the skill of science communication.

I have heard conflicting statements about the Hawthorne Effect and have tried to understand the science deeply enough to resolve those apparent conflicts and arrive at an essentially correct and sufficiently nuanced summary of the research. Here is what I found:

I’ll start with a recent systematic review of the published literature (always a good place to start). Here are the results and conclusions of a 2014 review:

Results

Nineteen purposively designed studies were included, providing quantitative data on the size of the effect in eight randomized controlled trials, five quasiexperimental studies, and six observational evaluations of reporting on one’s behavior by answering questions or being directly observed and being aware of being studied. Although all but one study was undertaken within health sciences, study methods, contexts, and findings were highly heterogeneous. Most studies reported some evidence of an effect, although significant biases are judged likely because of the complexity of the evaluation object.

Conclusion

Consequences of research participation for behaviors being investigated do exist, although little can be securely known about the conditions under which they operate, their mechanisms of effects, or their magnitudes. New concepts are needed to guide empirical studies.

From reading this and other reviews it seems that the evidence over the last century clearly shows that there is an experimenter effect when observing human behavior in social settings, like the work place. This experimenter effect, however, is not entirely an observer effect – a response to knowing that one is being observed. The term “Hawthorne effect,” therefore, has come to refer to a more general experimenter artifact and not just a specific observer effect.

Some more detail on the Hawthorne experiments is interesting and provides further background. They did, in fact, spend five years adjusting light levels for thousands of employees. They also had control groups in which they did not adjust light levels. In general every time they made a change there was an increase in productivity, regardless of the actual change. Both the control and active groups improved without statistical difference. This was true as long as the actual light levels did not produce a material problem – for example, when they dropped the light levels so low it became difficult to see, the workers complained.

They also varied break time, duration and intervals, with the same results. They gave shorter work days, which increased productivity per hour but if they decreased them too much daily productivity decreased.

There have been other experiments as well, that help put these results into further context. There was a series of teacher expectation experiments, for example. Teachers were told that one set of student performed well on an aptitude test and were expected to perform well. Over the next two years, those student performed better than the other students, even though the groups were actually equal at onset. Further, the teachers sometimes expressed annoyance at students in the low expectation group who did very well, exceeding expectations.

There were also the 1900 punch card experiments of Jastrow. One group of workers were told that their quota was 550 punch cards per day, which they were able to produce. When asked to increase their quota they indicated that this would be too difficult. The second group were not told anything, and they produced 2100 punch cards per day.

How to interpret all this?

Clearly, there are some interesting psychological effects going on here. To say this is all an observer effect would be a gross oversimplication, to the point of being wrong by missing important other effects. Possibilities include expectation, which is evident in the teacher and punch card experiments. Teachers have a great influence on the performance of their students, although it is still not clear exactly what the mechanisms are. That influence is biased by expectations, which is exactly why so much attention is paid to gender and race biases in teachers. It is also why we have to be very careful with labels, and also with using possibly biased standardized tests to establish expectations.

In the punch card experiments there seems to be a self-expectation bias. People’s perception of what is reasonable and even possible were easily established by creating a set point. I think this would now be described as part of the anchoring heuristic – expectations can be anchored to a specific value, and then later judgments use the anchor as a reference point. If you ask someone if an item is worth more or less than $10, then ask them how much they think it is worth, their guess will be much lower than if you initially asked them if it is worth more or less than $100.

Setting a quota is a strong manifestation of anchoring expectations.

More recently researchers have been thinking about the social and community aspects of these effects. Essentially, there is a work culture that influences the behavior of those in the group. That culture is altered by many variables, including anchoring of expectations. Also, however, being observed, and feeling as if management is taking an interest in your work conditions, or that you have some say in those conditions, will have an effect. The very notion that someone upstairs cares about details like the light level in your working space may have a profound effect on the work culture.

Workers also influence each other. They establish norms of behavior, and expectations for standards and productivity. In fact, the expectations of fellow workers may have more of an impact on behavior than management.

I recently received the following question from SGU listener Mike, which brings up another angle to this issue:

In my time working in an office I’ve seen many consultants come through the company and at times they seem to have an almost immediate impact/influence regardless of any tangible outcomes… I have thought for a while now that there might be a kind of ‘placebo effect’ coming in to play when a company hires an external consultant? Whether it’s influence of a big firm with a big reputation or just the act engaging an ‘expert’, managers seem to place a much higher value on an opinion from outside a company than from within it even if the opinions are exactly the same… and sometimes the advice is just flat out terrible but it’s still look upon very favorably.

I agree with the essence of the question – there is essentially an entire industry of corporate self-help that is selling the Hawthorne effect, even if their specific recommendations are speculative, nonsensical, or counter-productive.

This is also all very similar to the placebo effect, which like the Hawthorne effect is not one simple expectation effect but a complex web of interrelated effects that create the illusion of a specific response to a specific intervention when in fact they are just nonspecific responses to the act of having any intervention and assessing the outcome.

The self-help industry is largely selling placebo/Hawthorn effects as well. If people go on a diet, for example, the details of their diet don’t seem to matter (again, like the light levels, as long as they are not so extreme as to create a functional problem). The fact that they are paying attention to what they eat and trying to be more active has an effect.

Conclusion

The bottom line of all this is that – any intervention in almost any context will subjectively seem to work. There are a host of observational and psychological factors that will result in a real change in behavior, but also a biased assessment of the results.

This often leads to the false conclusion that the specific intervention (whether a treatment, a diet, a self-help strategy, or whatever) has specific efficacy, and therefore the underlying philosophy must be valid.

The Hawthorne/Placebo effect, interpreted broadly, is extremely far reaching. It must be considered when interpreting the results of any intervention. Only extremely careful isolation of variables allows for any conclusions about specific efficacy and therefore underlying theory.

The question that almost invariably flows next, however, is – can this type of effect be used in an ethical and positive way? I think the short answer is, it depends. It’s more complicated than you probably think. There are many pitfalls and downstream effects. and many things to consider.

My quick summary would be, however: In the context of medicine, I would not justify any intervention due to placebo effects alone.

In other contexts, such as making changes in the work place, I would not do anything that violates common sense, that seems extreme, or that violates normal ethical conduct just because it seems to create some improved outcome. However, benign and reasonable interventions, even if they have no specific effect, may be a sensible way to make people feel like you are paying attention, that you care, that their voice is being heard, and may therefore improve the culture of the workplace.

Just don’t buy into some wacky underlying theory if it seems to help.

I also think it is worthwhile to strip these nonspecific effects from the specific interventions that provoke them. In other words, we may be able to get the benefits of intervening without buying into implausible theories about specific interventions.

Current researchers are essentially saying the same thing – we need some new concepts for future research to isolate the real effects that are going on here.

At this point reality is more complex than even the experts have a handle on.