Jun 28 2016

Caffeine and Sleep

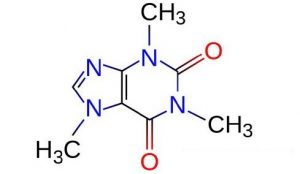

Caffeine is a drug. I think most people know that, but perhaps they don’t really think about it. Caffeine is essentially a legal unregulated drug (much like alcohol and nicotine, but with no age restriction).

Caffeine is a drug. I think most people know that, but perhaps they don’t really think about it. Caffeine is essentially a legal unregulated drug (much like alcohol and nicotine, but with no age restriction).

Coffee, tea, cola, and chocolate are all common sources of caffeine. Many people use this drug on a regular basis, often daily. They become addicted to this drug, and suffer withdrawal symptoms when they don’t take their regular dose. If caffeine were not readily available in commonly consumed food and drink, and say it were being introduced as a new drug, I wonder how it would be viewed and regulated.

A new study looks at the effects of caffeine on mental performance in those who are sleep deprived (a common application). Caffeine is a stimulant, it therefore does increase alertness and mental function. However, like all stimulants, its effects are a double-edged sword.

The study looked involved only 48 subjects, and had them restricted to 5 hours of sleep per night. Half were then given caffeine at 8 am and 12 noon while the other half were given placebos. For the first three days those taking caffeine performed better on mental tasks than those getting placebo. On days four and five, however, there was no difference.

The simplest way to interpret this study is that after three days the effects of chronic sleep deprivation overwhelm the stimulant effects of caffeine. The study did not look at whether this effect of caffeine could have been pushed further with a higher dose.

Another possibility is that the subjects getting daily caffeine were getting tolerant to its stimulant effects. The research on this is a bit mixed. Some tolerance does occur, but not to all of the effects of caffeine. It also probably takes more than three days to develop tolerance.

Some studies show that daily caffeine users develop tolerance to the alerting effects, and that the morning boost they feel when they drink caffeine may be mostly or entirely due to treating withdrawal from caffeine. There are probably some individual differences here as well.

As an aside, it is still debated whether caffeine should be considered addictive. It does not stimulate dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens, which is considered the hallmark of drug addiction. It does, however, share some features with addictive drugs, such as dopamine release in the frontal cortex. So perhaps it should be considered somewhat or possibly addictive, but not in the same class as cocaine or amphetamines.

Effects on sleep are mostly bad. The part of the brain most sensitive to caffeine are the parts that regulate the sleep-wake cycle. There is no question that caffeine disrupts sleep. Even when consumed as much as 6 hours prior to sleep, caffeine reduced sleep duration and quality. Another study showed that even an early AM caffeine dose can still be hanging around in the evening and reduce sleep quality.

Conclusion

There are a few takeaways from the existing research on caffeine. First, realize that caffeine is a stimulant drug, even though it is common in most human cultures.

Caffeine displays some tolerance (but not complete) and some addiction. If you get withdrawal symptoms, such as headache, then by definition you have some tolerance and should consider reducing or eliminating caffeine. I have “cured”

many patients of chronic headaches simply by advising them to eliminate caffeine. If you do have frequent headaches, consider eliminating caffeine for at least 6 weeks to see what effect it has.

For most people consuming 1-2 8oz cups of a caffeinated beverage in the morning is likely to have a stimulant effect and few side effects. As you increase the dose beyond that, you increase the risk of side effects or sleep problems.

If you have any sleep problems you should definitely avoid any caffeine beyond noon, and may want to even reduce or eliminate your morning caffeine. Caffeine does disrupt the sleep cycle by its direct effects on the brain, even at a low dose, doses which would not cause other side effects.

The biggest problem to avoid is using caffeine to treat daytime sleepiness which is caused by poor sleep. Caffeine does not sustainably compensate for the effects of sleep deprivation. It may work for a few days if you are not a regular user, but not beyond that. It does, however, disrupt sleep. So you could easily get into a vicious cycle in which you are using more caffeine to treat sleepiness due to poor sleep which is caused by the increasing doses of caffeine.

What I find is that many people take caffeine so much for granted that they don’t even consider its role in their symptoms. If you do have headaches or sleep problems, as least think about the role caffeine might be playing.