Dec

12

2023

Scientists have developed virtual reality goggles for mice. Why would they do this? For research. The fact that it’s also adorable is just a side effect.

Scientists have developed virtual reality goggles for mice. Why would they do this? For research. The fact that it’s also adorable is just a side effect.

One type of neuroscience research is to expose mice in a laboratory setting to specific tasks or stimuli while recording their brain activity. You can have an implant, for example, measure brain activity while it runs a maze. However, having the mouse run around an environment puts limits on the kind of real time brain scanning you can do. So researchers have been using VR (virtual reality) for about 15 years to simulate an environment while keeping the mouse in a more controlled setting, allowing for better brain imaging.

However, this setup is also limiting. The VR is really just surrounding wrap-around screens. But it is technically challenging to have overhead screens, because that is where the scanning equipment is, and there are still visual clues that the mouse is in a lab, not the virtual environment. So this is an imperfect setup. k

The solution was to build tiny VR goggles for mice. The mouse does not wear the goggles like a human wears a VR headset. They can’t get them that small yet. Rather, the goggles are mounted, and the mouse is essentially placed inside the goggle while standing on a treadmill. The mouse can therefore run around while remaining stationary on the treadmill, and keep his head in the mounted VR goggles. This has several advantages over existing setups.

Continue Reading »

Dec

11

2023

Not a crow.

One of the core tenets of scientific skepticism is what I call neuropsychological humility – the recognition that while the human brain is a powerful information processing machine, it also has many frailties. One of those frailties is perception – we do not perceive the world in a neutral or objective way. Our perception of the world is constructed from multiple sensory streams processed together and filtered through internal systems that include our memories, expectations, biases, assumptions and (critically) attention. In many ways, we see what we know, what we are looking for, and what we expect to see. Perhaps the most internet-famous example of this is the invisible gorilla, a dramatic example of inattentional blindness.

Far more subtle is what might be called cultural blindness – we can perceive differences that we already know exist or with which we are very familiar, but otherwise may miss differences as a background blur. On my personal intellectual journey, one dramatic example I often refer to is my perception before and after becoming a birder. For most of my life birds were something in the background I paid little attention to. My internal birding map consisted of a few local species and broad groups. I could recognize cardinals, blue jays, crows, pigeons, and mourning doves. Any raptor was a “hawk”. There were ducks and geese, and then there was – everything else. I would probably call any small bird a sparrow, if I thought to call it anything at all. I knew of other birds from nature shows, but they were not part of my world.

The birding learning curve was very steep, and completely changed my perception. What I called “crows” consisted not only of crows but ravens and at least two types of grackle. I can identify the field markings of several hawks and two vultures. I can tell the subtle differences between a downy and hairy woodpecker. At first I had difficulty telling a chickadee from a nuthatch, now the difference is obvious. I can even tell some sparrow species apart. My internal birding map is vastly different, and that affects how I perceive the world.

Continue Reading »

Nov

16

2023

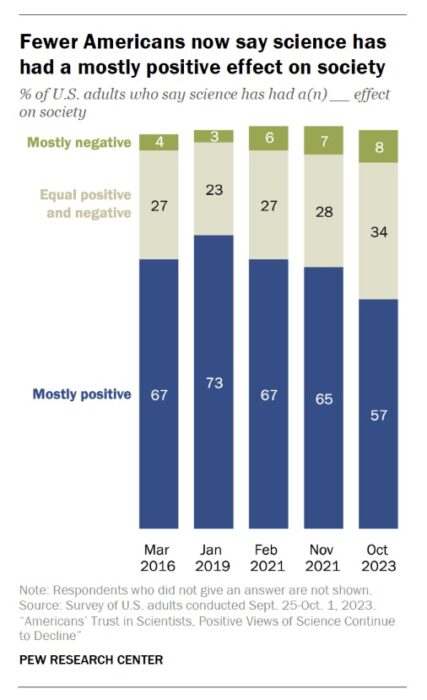

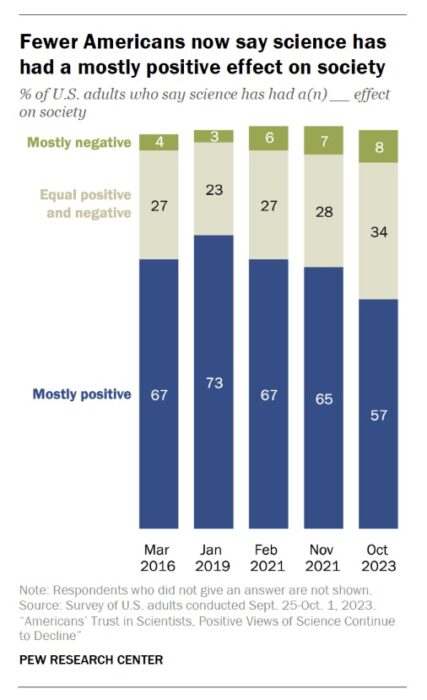

How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news – a recent Pew survey finds that trust in scientist has been in decline for the last few years. From its recent peak in 2019, those who answered that science has a mostly positive effect on society decreased from 73% to 57%. Those who say it has a mostly negative effect increased from 3 to 8%. Those who trust in scientists a fair amount or a great deal decreased from 86 to 73%. Those who think that scientific investments are worthwhile remain strong at 78%.

How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news – a recent Pew survey finds that trust in scientist has been in decline for the last few years. From its recent peak in 2019, those who answered that science has a mostly positive effect on society decreased from 73% to 57%. Those who say it has a mostly negative effect increased from 3 to 8%. Those who trust in scientists a fair amount or a great deal decreased from 86 to 73%. Those who think that scientific investments are worthwhile remain strong at 78%.

The good news is that these numbers are relatively high compared to other institutions and professions. Science and scientists still remain among the most respected professions, behind the military, teachers, and medical doctors, and way above journalists, clergy, business executives, and lawyers. So overall a majority of Americans feel that science and scientists are trustworthy, valuable, and a worthwhile investment.

But we need to pay attention to early warning signs that this respect may be in jeopardy. If we get to the point that a majority of the public do not feel that investment in research is worthwhile, or that the findings of science can be trusted, that is a recipe for disaster. In the modern world, such a society is likely not sustainable, certainly not as a stable democracy and economic leader. It’s worthwhile, therefore, to dig deeper on what might be behind the recent dip in numbers.

It’s worth pointing out some caveats. Surveys are always tricky, and the results depend heavily on how questions are asked. For example, if you ask people if they trust “doctors” in the abstract the number is typically lower than if you ask them if they trust their doctor. People tend to separate their personal experience from what they think is going on generally in society, and are perhaps too willing to dismiss their own evidence as “exceptions”. If they were favoring data over personal anecdote, that would be fine. But they are often favoring rumor, fearmongering, and sensationalism. Surveys like this, therefore, often reflect the public mood, rather than deeply held beliefs.

Continue Reading »

Oct

23

2023

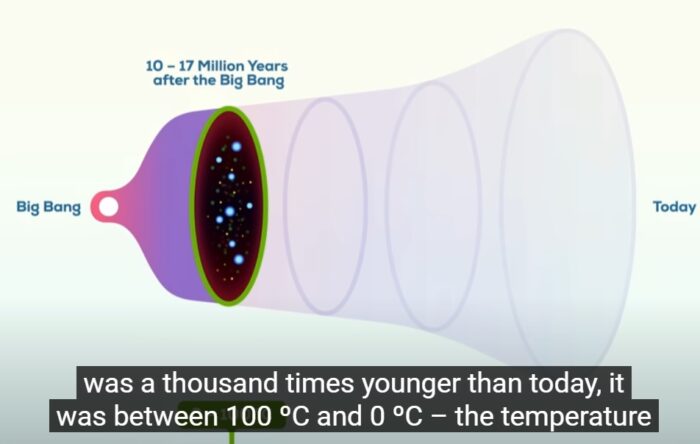

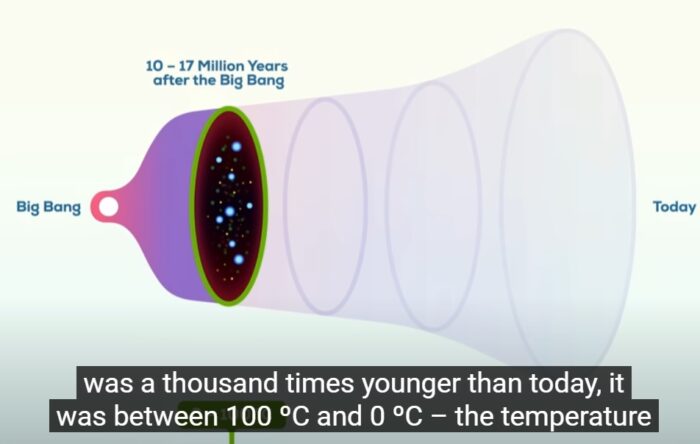

Recently I was asked what I thought about this video, which suggests it is possible that life formed in the early universe, shortly after the Big Bang. Although no mentioned specifically in the video, the ideas presents are essentially panspermia – the idea that life formed in the early universe and then spread as “seeds” throughout the universe, taking root in suitable environments like the early Earth. While the narrator admits these ideas are “speculative”, he presents what I feel is an extremely biased favorable take on the ideas being presented.

Recently I was asked what I thought about this video, which suggests it is possible that life formed in the early universe, shortly after the Big Bang. Although no mentioned specifically in the video, the ideas presents are essentially panspermia – the idea that life formed in the early universe and then spread as “seeds” throughout the universe, taking root in suitable environments like the early Earth. While the narrator admits these ideas are “speculative”, he presents what I feel is an extremely biased favorable take on the ideas being presented.

The video starts by arguing that life on Earth arose very quickly, perhaps implausibly quickly. The Earth is 4.5 billion years old, and it likely cooled sufficiently to be compatible with life around 4.3 billion years ago. The oldest fossils are 3.7 billion years old, which leaves a 600 million year window in which life could have developed from prebiotic molecules. When during that time did these complex molecules cross the line to be considered life is unknown, but it seems like there was probably 1-2 hundred million years for this to happen. The video argues that this was simply not enough time – so perhaps life already existed and seeded the Earth. But this argument is not valid. We do not have any information that would indicate something on the order of 100 million years was not enough time for the simplest type of life to form. So they set up a fake problem in order to introduce their unnecessary “solution”.

But the argument gets worse from there. Most of the video is spent speculating about the fact that between 10 million and 17 million years ago the temperature of the universe would have been between 100 C and 0 C, the temperature range of liquid water. During this time, life could have formed everywhere in the universe. But there is a glaring problem with this argument, that the video hand-waves away with a giant “may”.

Continue Reading »

Jul

27

2023

I recently wrote about electric vehicles, which sparked a lively discussion in the comments. There was enough discussion that I wanted to pull my responses together into a new post. Before I get to the details, some general observations. The conversation, in my opinion, nicely demonstrates a couple of general critical thinking principles. The first is that basically well-meaning people (meaning they are not a paid shill) can look at essentially the same collection of facts and come to a different opinion. This relates partly to another post I wrote recently, about how we can subjectively define “true” in order to support pre-existing narratives.

The other principle on clear display in the comments is our old friend confirmation bias (this cuts in all directions, although not necessarily symmetrically). We tend to seek out, accept, and remember bits of information that seem to support what we already believe or want to believe, while finding reasons to dismiss or ignore information that contradicts our narrative. The result is a powerful illusion of knowledge, that what we feel in our guts (or aligns with our ideology) is objectively and obviously true. Therefore, those who disagree with us must be suffering some catastrophic personal failing.

There are also external factors at play, because we are not living in a neutral or disinterested information ecosystem. Not only are we biased in how we gather facts, information is being curated for us with the specific purpose of influencing what we believe to be true. This is also a self-reinforcing phenomenon, because acceptance of curated information leads us to increasingly curated and extreme sources of information, sometimes leading to the infamous “information bubble”.

Continue Reading »

Jul

21

2023

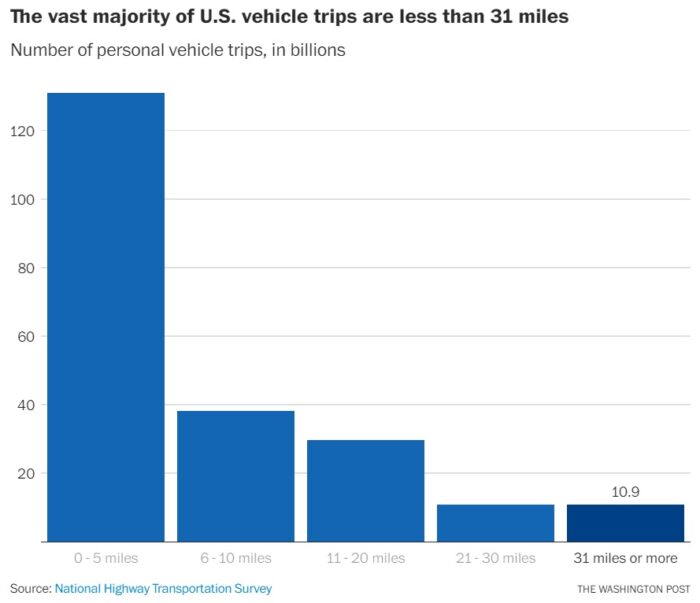

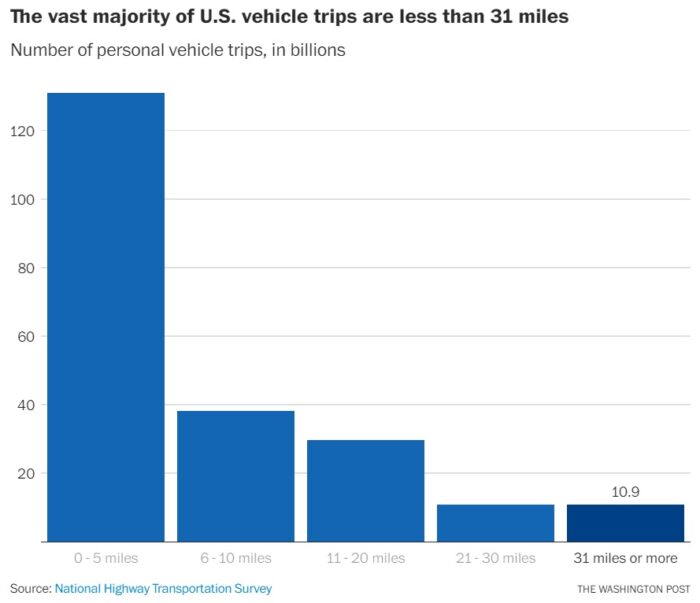

One of the key components of the plan to get our civilization to net zero by 2050 is to transform the motor vehicle fleet into all electric vehicles (EVs). This is a worthy goal, as it would eliminate burning gasoline for transportation. In fact it’s necessary if we want to get near net zero. Governments and the auto industry are responding with incentives for EVs, some regulations forcing the phasing out of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and investment of billions even trillions of dollars to change over production lines, secure raw material sources, and build charging stations.

One of the key components of the plan to get our civilization to net zero by 2050 is to transform the motor vehicle fleet into all electric vehicles (EVs). This is a worthy goal, as it would eliminate burning gasoline for transportation. In fact it’s necessary if we want to get near net zero. Governments and the auto industry are responding with incentives for EVs, some regulations forcing the phasing out of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and investment of billions even trillions of dollars to change over production lines, secure raw material sources, and build charging stations.

But EVs have their critics. And some experts point out (a valid point I completely agree with) that we have to consider the optimal pathway to net zero, not just the destination. By 2050 EVs will be an even more mature technology than they are now, and batteries will have at least 4-5 times the energy density. We may also have battery designs that use more abundant and less problematic raw material. Also by then there should be a robust infrastructure of charging stations, and a green energy grid to support them. So it’ easy to imagine the world of 2050 with an all EV transportation infrastructure that is as close to net zero as possible.

I also have to say, I own a Tesla and it’s the best car I ever owned. The driving experience is great – once you get used to the regenerative breaking, you have more and easier control. Acceleration is instantaneous. Charging at home every night is easy, and you never have to visit a gas station. There is literally almost no maintenance – no oil changes, no tune-ups, no engine parts that wear out. The break pads last much longer because you very rarely use the breaks. At least along the East coast, long trips are no problem.

But what is the optimal path to get to full EV? And this is not just about getting there quickly. EVs may not be the best option for everyone right now. The optimal path may go through bridging technologies, most notably plug-in hybrids. What are the downsides to EVs?

Continue Reading »

Jul

18

2023

Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts.

Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts.

Knowing facts is still important, because you cannot think in a vacuum. Our internal model of the world is build on bricks of fact, but before we take a brick and place it in our wall of knowledge, we have to decide if it is probably true or not. I have come to think about this in terms of three categories of skills – domain knowledge (with scientific claims this is scientific literacy), critical thinking, and media savvy.

Domain knowledge, or scientific literacy, is important because without a working knowledge of a topic you have no basis for assessing the plausibility of a new claim. Does it even make basic sense? An easily refutable claim may be accepted simply because you don’t know it is easily refutable. Critical thinking skills involve an understanding of the heuristics we naturally use to estimate truth, our cognitive biases, cognitive pitfalls like conspiracy thinking, how motivation affects our thought processes, and mechanisms of self deception. Media savvy involves understanding how to assess the reliability of information sources, how information ecosystems work, and how information is used by others to deceive us.

A recent study involves one aspect of this latter category – how do we assess the reliability of information sources and how this affects our bottom line assessment of whether or not something is true. The researchers did two studies involving 1,181 subjects. They gave the subjects factual information, then presented them with claims made by a media outlet. They were further told whether the media outlet intended to inform or deceive on this topic. They studies claims that are considered highly politicized and those that were not.

What they found is that subjects were more likely to deem a claim true if it came from a source considered to be trying to inform, and more likely to be false when the source was characterized as trying to deceive – even if the claims were the same. At first this result seems strange because the subjects were told the actual facts, so they knew absolutely (within the confines of the study) whether or not the claim was true.

Continue Reading »

Jun

30

2023

The climate change discussion would benefit most from good-faith evidence and science-based discussion. Unfortunately, humans tend to prefer emotion, ideology, motivated reasoning, and confirmation bias. As an example, I was sent an excerpt from a climate change podcast as a “rebuttal” to my position. The content, however, does not address my actual position, and I find many of the arguments highly problematic. This one is coming from a perspective that climate change is real and a definite problem that needs to be addressed, but seems to be advocating that the best solution is to be all-in on wind and solar without needing other solutions.

The climate change discussion would benefit most from good-faith evidence and science-based discussion. Unfortunately, humans tend to prefer emotion, ideology, motivated reasoning, and confirmation bias. As an example, I was sent an excerpt from a climate change podcast as a “rebuttal” to my position. The content, however, does not address my actual position, and I find many of the arguments highly problematic. This one is coming from a perspective that climate change is real and a definite problem that needs to be addressed, but seems to be advocating that the best solution is to be all-in on wind and solar without needing other solutions.

The podcast is The Energy Transition Show and here is the episode I was sent: https://xenetwork.org/ets/episodes/episode-200-ets-retrospective/. As a rebuttal to my position and what seems to be the position of many experts, their arguments are strawmen, but a particular kind of strawmen. One way to create a strawman argument it to portray the most extreme position as “the” counter opinion to your own. This sets up a false dichotomy – either you agree with us or you are advocating for this extreme and easily refutable position, ignoring vast territory between two extremes. Here’s the beginning of the excerpt:

[00:34:15] ….this argument against the energy transition, which seems to be falling by the wayside since you started in 2015, is this claim that we could never run a power grid with a large share of renewables due to their quote unquote intermittency? Right. You know, back in 2015, there were a lot of people insisting that the power grid couldn’t support more than maybe a high single digit, low double digit percentage of renewable power due to this intermittency, and that we would need to maintain significant amounts of baseload generators that run close to full time, like coal, nuclear plants, to ensure reliable operation of the power grid. But that has not turned out to be true, at least not yet, at the levels of penetration we’re seeing and we’re seeing very high levels of penetration in California. A couple weeks ago, I think 97% renewables at one point in time. And so I don’t really hear those arguments nearly as often anymore. But I am very interested in where you think those arguments have gone.

[00:35:55] Chris Nelder: Yeah, well, we were just talking about terminology and the preference of some people to start calling natural gas fossil gas or methane. I have a strong aversion to the term intermittency. That’s a term that really I think came from the fossil fuel industry as a way of casting doubt on renewables and making them sound unreliable or hard to forecast or in some way or another, not something that we can count on. And that’s just not the case.

The notion that the grid cannot take more than single digits or low double digits of intermittent sources may be a talking point on the climate change denial end of the spectrum, but that is not the mainstream perspective arguing that we should not rely entirely one wind and solar. Also, I have never read the argument from any expert that the grid cannot function with high penetration of wind and solar, only that it becomes more challenging and high penetration. One side note, many sources use the term “renewable” source or explicitly refer to WWS – wind, water, and solar. But hydropower is not intermittent, it can be dispatchable, and can be use for grid storage through pumped hydro. So including that in the discussion muddies the waters.

Continue Reading »

Jun

19

2023

In my last post I noted that even mentioning general vague support for the LGBTQ community was enough to trigger very specific feedback, often making erroneous scientific claims. Each claim requires a deep dive and article-length discussion. Even though the discussion that followed in the comments was better than I thought it would be, it still filled with additional dubious claims. I suspect there are two main reasons for this. The first is that the topic of gender identity is complex and not intuitive. It may feel intuitive, as if your immediate gut reaction is all that is necessary to deal adequately with the topic, but it really isn’t. Ultimate this topic deals with how our brains construct our own sense of self, identity, and reality. These are always tricky concepts to deal with – and as I have pointed out before in other contexts, our brain constructs are counterintuitive by their very nature. In other words, our brains evolved for these constructs to feel real and automatic, and for the subconscious processes that create them to be invisible to us.

Second, the issue of gender identity has been highly politicized. This has resulted in any discussion of the topic being flooded with biased and deliberate misinformation. The usual FUD (fear, uncertainty doubt) strategies apply. And of course – science is hard. Even seemingly straightforward questions are actually quite complex. This makes it easy to create confusion by “just asking questions” or selectively applying skepticism.

One question at the heart of the trans issue is this – what is the rate of regret or even detransitioning after medical transition? One narrative is that adolescents (often conflated with “children”) are being prematurely herded down a road to transition, which they later regret. The other narrative is that, generally speaking, making the decision to transition is taken very seriously, with very low levels of later regret. Which is true?

Continue Reading »

Jun

16

2023

On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”

On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”

Being trans itself is not considered a mental illness, but this deserves some extensive discussion. It’s important to first establish some basic principles, starting with – what is mental illness? This is a deceptively tricky question. The American Psychiatric Association provides this definition:

Mental illnesses are health conditions involving changes in emotion, thinking or behavior (or a combination of these). Mental illnesses can be associated with distress and/or problems functioning in social, work or family activities.

But this is not a technical or operational definition (something that requires book-length exploration to be thorough), but rather a quick summary for lay readers. In fact, there is no one generally accepted technical definition. There is some heterogeneity throughout the scientific literature, and it may vary from one illness to another and one institution to another. But there are some generally accepted key elements.

First, as the WHO states, “Mental disorders involve significant disturbances in thinking, emotional regulation, or behaviour.” But then we have to define “disorder”, which is typically defined as a lack or alternation in a function possessed by most healthy individuals that causes demonstrable harm. “Significant” is also a word that’s doing a lot of heavy lifting there. This is typically determined disorder by disorder, but usually includes elements of persistent duration for greater than some threshold, and some pragmatic measure of severity. For example, does the disorder prevent someone from participating in meaningful activity, productive work, or activities of daily living? Does it provoke other demonstrable harms, such as severe depression or anxiety? Does it entail increased risk of negative health or life outcomes?

Continue Reading »

Scientists have developed virtual reality goggles for mice. Why would they do this? For research. The fact that it’s also adorable is just a side effect.

Scientists have developed virtual reality goggles for mice. Why would they do this? For research. The fact that it’s also adorable is just a side effect.

How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news –

How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news – Recently I was asked what I thought about

Recently I was asked what I thought about

One of the key components of the plan to get our civilization to net zero by 2050 is to transform the motor vehicle fleet into all electric vehicles (EVs). This is a worthy goal, as it would eliminate burning gasoline for transportation. In fact it’s necessary if we want to get near net zero. Governments and the auto industry are responding with incentives for EVs, some regulations forcing the phasing out of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and investment of billions even trillions of dollars to change over production lines, secure raw material sources, and build charging stations.

One of the key components of the plan to get our civilization to net zero by 2050 is to transform the motor vehicle fleet into all electric vehicles (EVs). This is a worthy goal, as it would eliminate burning gasoline for transportation. In fact it’s necessary if we want to get near net zero. Governments and the auto industry are responding with incentives for EVs, some regulations forcing the phasing out of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and investment of billions even trillions of dollars to change over production lines, secure raw material sources, and build charging stations. Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts.

Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts. The climate change discussion would benefit most from good-faith evidence and science-based discussion. Unfortunately, humans tend to prefer emotion, ideology, motivated reasoning, and confirmation bias. As an example, I was sent an excerpt from a climate change podcast as a “rebuttal” to my position. The content, however, does not address my actual position, and I find many of the arguments highly problematic. This one is coming from a perspective that climate change is real and a definite problem that needs to be addressed, but seems to be advocating that the best solution is to be all-in on wind and solar without needing other solutions.

The climate change discussion would benefit most from good-faith evidence and science-based discussion. Unfortunately, humans tend to prefer emotion, ideology, motivated reasoning, and confirmation bias. As an example, I was sent an excerpt from a climate change podcast as a “rebuttal” to my position. The content, however, does not address my actual position, and I find many of the arguments highly problematic. This one is coming from a perspective that climate change is real and a definite problem that needs to be addressed, but seems to be advocating that the best solution is to be all-in on wind and solar without needing other solutions. On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”

On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”