Feb 28 2022

Some Good News on Climate Change

One of the challenges of being a science communicator is keeping up to date. About 2.5 million scientific papers are published every year. Most of this is noise, preliminary studies, speculations, etc., but the end result is that most fields of science are constantly changing. This became very concrete for me while writing my next book (shameless plug alert), The Skeptics Guide to the Future, coming out this Fall. A big part of the book is examining cutting edge science and technology and then extrapolating it into the near, midterm, and far future. During the editing process there were constantly science news items that required small updates to the book. In fact I had to ask my editor, after the final submission, if I could please squeeze in one more update, and promised it would be the last one.

One of the challenges of being a science communicator is keeping up to date. About 2.5 million scientific papers are published every year. Most of this is noise, preliminary studies, speculations, etc., but the end result is that most fields of science are constantly changing. This became very concrete for me while writing my next book (shameless plug alert), The Skeptics Guide to the Future, coming out this Fall. A big part of the book is examining cutting edge science and technology and then extrapolating it into the near, midterm, and far future. During the editing process there were constantly science news items that required small updates to the book. In fact I had to ask my editor, after the final submission, if I could please squeeze in one more update, and promised it would be the last one.

If you are not paying obsessive attention to a particular field of science, it’s really difficult to keep completely up to date. There is also a substantial delay, sometimes decades, between changes to the consensus of scientific opinion based on new evidence and when that new consensus filters down to the public’s general consciousness. Sometime the delay is forever, as outdated ideas persist indefinitely. This is especially true if an outdated scientific conclusion has a rhetorical utility, either in marketing a product or promoting a political ideology. We figured out a quarter of a century ago that consuming anti-oxidants were not good for your health, but don’t hold your breath for the supplement industry to alter their promotion of anti-oxidant products.

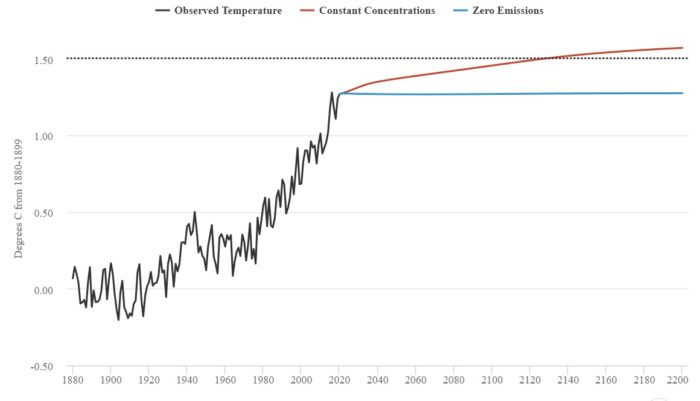

One idea that has become a standard part of the conversation on climate change is that once CO2 is released into the atmosphere it will cause continued warming for decades. So, the argument goes, even if we stopped all release of greenhouse gases today, full net-zero, the climate would continue to warm for many decades, perhaps a century or longer. That was the scientific consensus, although it was never a very firm one, just the best estimate based on existing evidence. That conclusion, however, started to crack as early as 2008, and by 2020 was updated with new and better science. This is a rare instance of good climate news. In an interview, climate scientist Michael Mann said:

“This really is true,” he said. “It’s a dramatic change in the paradigm that has been lost on many who cover this issue, perhaps because it hasn’t been well explained by the scientific community. It’s an important development that is still under appreciated. It’s definitely the scientific consensus now that warming stabilizes quickly, within 10 years, of emissions going to zero.”

The update results from a better understanding of how warming affects the carbon cycle itself. Another way to look at this is that the time it would take for the entire system to reach a new temperature homeostasis is shorter than we thought. The new equilibrium point after release of new carbon into the atmosphere is reach after about one decade, rather than multiple decades. We should also not overstate the implications of this. First, the one decade timeline is for most of the resulting warming, but there is still a long tail of a small amount of warming that can last for decades or longer.

Further, this does not mean that after a decade or so the resulting warming goes away. It doesn’t. Once that new warmer equilibrium point is reached it will last for thousands of years, assuming no further human-caused changes to the carbon cycle. Slowly over time carbon will combine with minerals forming carbonates in rocks. Eventually, again after thousands of years, a new equilibrium point will be reached.

What does this mean for climate change now? The obvious good news is that if we do actually manage to reduce our CO2 emissions, the effects of already-released carbon will not cause continued further warming as long as we thought. So our ability to stop further warming is greater than previous estimates. This is an important realization, and useful for countering climate nihilism. Some have argued that it’s already too late, that the warming that will occur from CO2 already released is enough to cause catastrophic climate change. This has never been a good argument, because things can always get worse. Yes, there are likely irreversible tipping points we don’t want to cross, but generally climate change is a sliding scale. Just because it will be bad does not mean we should not make an effort to keep it from getting even worse.

And now we can be emboldened by the realization that we can stop further warming in about a decade if we can manage to achieve net-zero emissions. We can then use carbon sequestration to reduce CO2 and bring temperatures down closer to their recent historical levels. In fact, perhaps one day we will be adjusting the amount of CO2 in the system to achieve some ideal level. But at the very least, relative stability on a civilization timescale would be nice.