Jul 14 2020

Imagining vs Seeing

Try to conjure up a mental image of a bicycle (without referencing a picture). Better yet, try to draw a bicycle. Most people (75% or more) cannot draw an accurate bicycle from memory. There are a lot of layers here. First, people tend to grossly overestimate their specific or technical knowledge, especially of everyday objects and processes. I often like to challenge myself with the caveman thought experiment. If I suddenly found myself 20,000 years in the past living with pretechnological humans, how much technology could I bootstrap from my own knowledge? The answer is – surprisingly little (unless you are an expert in such things).

Try to conjure up a mental image of a bicycle (without referencing a picture). Better yet, try to draw a bicycle. Most people (75% or more) cannot draw an accurate bicycle from memory. There are a lot of layers here. First, people tend to grossly overestimate their specific or technical knowledge, especially of everyday objects and processes. I often like to challenge myself with the caveman thought experiment. If I suddenly found myself 20,000 years in the past living with pretechnological humans, how much technology could I bootstrap from my own knowledge? The answer is – surprisingly little (unless you are an expert in such things).

There is also the fact that we tend to overestimate the detailed accuracy of our memories. How many times have you seen a bike, and yet you cannot conjure up an accurate image of one in your brain. Perception itself is also limited – we tend to see what we pay attention to, and perception is highly filtered through our memory and expectation. I experienced this first hand when I started birding. Birds I had lived with my entire life suddenly became visible to me.

There is also the layer of – what is the neurological difference between imagining and seeing? Neuroscientists have already demonstrated that when we imagine or remember an image we use the same visual cortex as when we actually see an image. This makes sense because the visual cortex is organized in order to represent visual images, whether we are seeing, remembering, or imagining those images. In fact, there is probably little to no difference between remembering and imagining, but that is a topic for another day. What I want to explore further is a recent study that looked at the difference between seeing and imagining.

The researchers addressed this question in two ways. First they used a neural network designed to create and process images, and further designed to mimic the functional organization of the human brain. Specifically the neural network had basic or primary visual processing, and then more higher level visual processing. The researchers found that when creating an image the system activated the primary visual processing more diffusely but in less detail then when “seeing” an image. The researchers used this as a prediction and then studies human brains with fMRI to see if the computer model predicted human brain activity.

As an aside, remember that fMRI research that attempts to localize brain regions based on activity needs to be taken with a grain of salt. Unless there were adequate internal replications, such data may not be reliable. But that aside, let’s look at what this study found.

As predicted, subjects that were asked to imagine something had a similar pattern of brain activity to the neural networks, compared to brain activity while viewing the same thing. During imagination, the primary visual cortex lit up more diffusely and with less detail. When viewing an image less of the primary visual cortex lit up, but a voxel by voxel analysis showed greater detail. In short, on a neurological level, our imaginations appear to be fuzzy, and this matched what was seen in neural networks designed to process visual images.

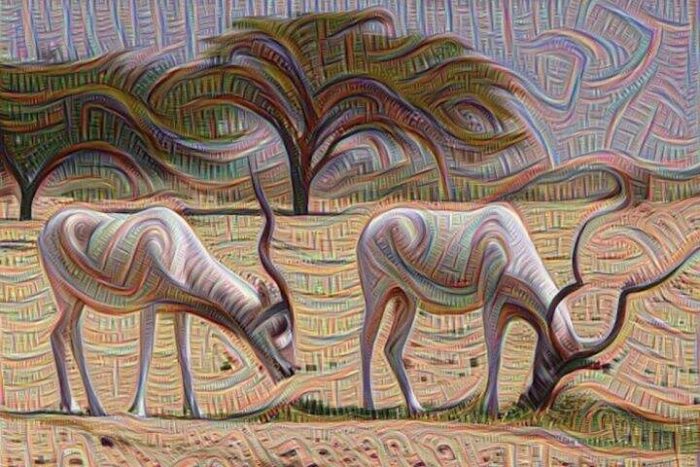

If this result holds up in future research and replications, it will provide a neurological basis for the psychological research showing the limits of human memory and imagination. These two approaches are producing the same answer – we imagine in broad brush-strokes without technical detail or accuracy. This study also adds the further detail that this fuzziness occurs a the level of the primary visual cortex – what we actually see.

Remember the relationship between the primary visual cortex and higher cortical areas. These secondary visual areas provide context and meaning to what we see. But the direction of communication runs both ways – once our higher visual cortical areas match what we are seeing with a specific item from memory, such as a bicycle, it sends that information back down to the primary visual cortex and essentially tells it to make the image look more like a bicycle. The final experience represents an interplay between these layers. The result is a visual fiction, but one that allows us to interact with and make sense of the world around us. But apparently this does not require a lot of detail or technical accuracy.

When we imagine we are still forming an image with our visual cortex, but the input is not coming from the retina. Rather it is coming from a combination of our memory and the creative parts of our brain, and the input these areas provide to the primary visual cortex is more diffuse and less detailed than information coming from the retina.

I also find it interesting that we have such little awareness of all this. Most people not only could not accurately draw a bicycle, they massively overestimated their ability to do so. They were simply not aware of the fact that their memory of a bicycle was fuzzy and lacked detail.

However, it also seems that our brains can function in different “modes” related to attention. We can consciously direct our attention, and this includes directing our attention to details (something we may not do by default). The ability to attend to detail is also dependent on our knowledge base (essentially our internal model of reality). To circle back to my bird analogy – when I looked at birds with my pre-birder mental eyes, I saw a little brown bird, or a little black bird, and maybe recognized a few distinct and common birds like blue jays and cardinals. But I could not reproduce even a cardinal from memory in any technical detail. Try it. Did you notice or remember that cardinals have black faces? Can you imagine the precise shape of their beak?

After I learned how to recognize birds, then I had the ability to notice and attend to certain details, such as the size and shape of the beak, specific coloring patterns, the size of the tail feathers, and even the pattern of its wing flaps during flight.

The same is true for any area of knowledge. The more you know, the more you see. Artists in particular look at the world with an artist’s eyes, seeing details that would be necessary to reproduce something they see. They have to pay attention to ratios and relative sizes, as well as subtleties of color that non-artists may just gloss over. Meanwhile, engineers notice details in technology that others might not even see exists.

Probably the next time you look at a bike or a picture of a bike, you will look at the detail, and not just the gestalt, and maybe even try to commit those details to memory. Then when you try to imagine a bike it will be more accurate. Perhaps further research will look at the difference in brain activity between these two states – someone with detailed memory and someone without.