Nov 22 2022

Genes and Language

There are now approximately 8 billion people on the planet. In addition, there are over 7,100 languages spoken on Earth. One question for anthropologists and linguistic experts is – how closely do genetic relationships match language relationships. Both language and genes are generally inherited from our parents – well, genes absolutely, but language generally. It makes sense that a map of genetic relatedness would closely follow a map of linguistic relatedness. If we zoom out from a single family to a population, the question becomes a bit more complex. Populations can mix genes with other populations. Two populations that derived relatively recently from a common population will likely be genetically similar, and even if their current languages differ, they too likely share a common root and therefore lots of similarities.

There are now approximately 8 billion people on the planet. In addition, there are over 7,100 languages spoken on Earth. One question for anthropologists and linguistic experts is – how closely do genetic relationships match language relationships. Both language and genes are generally inherited from our parents – well, genes absolutely, but language generally. It makes sense that a map of genetic relatedness would closely follow a map of linguistic relatedness. If we zoom out from a single family to a population, the question becomes a bit more complex. Populations can mix genes with other populations. Two populations that derived relatively recently from a common population will likely be genetically similar, and even if their current languages differ, they too likely share a common root and therefore lots of similarities.

What happens, then, when scientists overlay the genetic and linguistic maps of humanity? A recent study does just that. To do this they compiled a massive database, called GeLaTo, or Genes and Languages Together. GeLaTo includes data from “4,000 individuals speaking 295 languages and representing 397 genetic populations.” That is fairly robust, but there is also lots of room for continuing to add information to the database to add more precision and detail to any analysis.

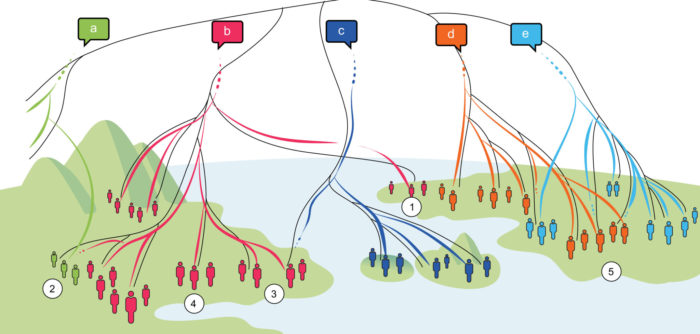

What they found is that the match between genes and language is very good, about 80%. However, that still leaves 20% of identified genetic populations with a language mismatch. How does this happen? It doesn’t take much imagination to think of a scenario where a population takes on the language of another population in their region that is genetically distinct. For example:

Some peoples on the tropical eastern slopes of the Andes speak a Quechua idiom that is typically spoken by groups with a different genetic profile who live at higher altitudes. The Damara people in Namibia, who are genetically related to the Bantu, communicate using a Khoe language that is spoken by genetically distant groups in the same area. And some hunter-gatherers who live in Central Africa speak predominantly Bantu languages without a strong genetic relatedness to the neighboring Bantu populations.

Of course, “mismatch” is relative (not a binary), because the degree of relatedness for languages and genes is relative. In the examples above, the people are still speaking languages from other populations in their region, but the linguistic match is much closer than the genetic match. It seems the primary mechanism for such mismatches is conquest, either culturally, economically, or militarily. One population imposes its language on another, genetically distinct, population.

The study also looked at the relative divergence times for language and genes for related populations. In other words, if you have two populations that are somewhat related, how far in the past did those populations genetically diverge, and how far in the past did their languages diverge? They found that these two times rarely matched, suggesting that different processes are at work. They also looked at mismatches across that past 10,000 years and around the world. They found that mismatch events are scattered throughout time and space, indicating that they are fairly universal and common events.

One way to think about what we are seeing here is the difference between biological evolution and cultural evolution. Biological evolution requires a direct genetic connection through inheritance (vertical transmission), punctuated by occasional events of horizontal gene transfer (for example, through viruses inserting DNA). Biological evolution requires an unbroken chain. It also has to work with the material at hand, and has to move forward. This means that evolution cannot invent new genes from nothing. It can duplicate and alter genes, however. Evolution also cannot erase its own history. It cannot go backwards. Primates, for example, can evolve into further variations on primates, but cannot evolve into fish.

Cultural evolution does not have any of these absolute restraints. New ideas can be created from whole cloth. Horizontal transfer is also much more common and profound. The question of whether or not culture can go back in time is interesting. My sense is that the answer is generally no – that would require a degree of cultural amnesia which is likely not possible. We may repeat historical patterns, but modified in detail by the intervening history. We can’t, for example, go back to the 19020s and replay history.

Cultural evolution also includes more than just language. Language probably is one of the aspects of culture that follows a genetic pattern most closely, because we learn our primary language when we are young and the transmission of language is generally very organic. Technology is also an aspect of cultural evolution, but seems far more transmissible than language. A culture can simply adopt wholesale a technological advance of another population, much more easily than it can adopt a language. Because of the pressures of competition, advances in technology seem to be readily adopted.

But it is interesting the degree to which we can see evolutionary patterns in the changes of technology and other aspects of culture over time. Culture does have an amazing inertia, because that is how human brains work. We absorb the culture in which we are raised, it shapes our brain in profound and subtle ways, often to such a degree that we are not even aware of our cultural biases. We really can only know about them by being exposed to other cultures. I am most fascinated by variables that I did not even know were variables until I learned that another culture was different. For example, social distance (how far apart do you stand from someone in various social situations) is a cultural variable I took for granted until I learned that they can differ in other cultures.

I would like to see cultural maps of things other than language, and how they match to genetic and linguistic maps. I wonder if more subconscious cultural behavior (like social distance) matches better than overt aspects, like language. A conquering population may impose their language on another population, but are they going to consciously impose their social distance? There is lots of room for further research here.