Apr 16 2020

Children Like to Ask Why

This should come as no surprise to any parent – children appear to prefer books that are loaded with causal information, meaning they address the questions of why, not just what. That children have a preference for causal information has already been established in the lab, but the new study claims to be the first to show this effect outside the lab in a more real-world setting.

This should come as no surprise to any parent – children appear to prefer books that are loaded with causal information, meaning they address the questions of why, not just what. That children have a preference for causal information has already been established in the lab, but the new study claims to be the first to show this effect outside the lab in a more real-world setting.

The study itself adds only a small bit of information, but is useful as far as it goes. The researchers had adult volunteers read two books to 48 children. The books were carefully matched in every way, except one book gave information about animals, while the other book also gave explanations for why animals had the traits and behaviors that they do. The children seemed to engage equally with both books, but afterwards expressed a clear preference for the book rich with causal information.

This is a reasonable confirmation of the laboratory-based research, but really doesn’t go that far. What we would like to know is if this stated preference predicts anything concrete. Are children more likely to read books with causal information, to read them longer, to absorb and retain more information, etc.? Does that affect their academic performance later in life? It makes sense that it would, but we need evidence to be sure.

We do know that reading aloud to young children is associated with better literacy outcomes. Simply having more books in the home is linked to better academic achievement (although this kind of data is rife with confounding factors, like socioeconomic status). Early academic skills, like reading, predict later academic success. Therefore anything that increases children’s motivation and enjoyment of reading is likely to have a positive effect. The hope is that information like this will allow for better targeting of books to children to engage their reading.

But even putting literacy and academic achievement aside, addressing putative causality is a better way to teach scientific knowledge, I think at any age. That last point is important to address – how do we best communicate science to a variety of audiences by age and background? Overall I think it’s best not to underestimate your audience and to aim a little high. The only caveat there is to avoid relying on specific technical terminology or background knowledge.

To explore this question further, let’s breakdown the different layers of information as I see it. The most basic information is simple factual statements – tigers are white, black, and orange. The value of factual information should not be underestimated or minimized. Concepts are important also, but concepts have to hang on facts – it is the interaction between the two that people need to grasp. But just “dry” facts don’t accomplish much on their own, and don’t engage curiosity. The next layer is why are tigers those colors? Because it provides camouflage in their jungle environment. This introduces the concept of camouflage and provides a reason “why” tigers are the color they are.

How camouflage works is a deeper causal question, and specifically why are orange tigers camouflaged in a green jungle? Well, most of their prey are dichromats who do not distinguish between green and orange, so to their eyes tigers blend in with their surroundings. We can go deeper still. How did the tiger get its camouflage. That is where evolution comes in, and we can dive pretty deep on how evolution works, selective pressures, and population genetics.

But there is yet another layer to science communication – how do we know this and with how much confidence? This gets to how we build scientific knowledge through science-based methodology. That is ultimately what we want everyone to have at least a basic understanding of, how do we know what we claim to know? How does knowledge itself work? This ties into the final layer of knowledge, and that is dealing with controversies, schools of thought, differences of opinion, minority and even fringe beliefs.

I’m not recommending that we dive into heated controversies to answer basic questions from 5 year-olds. But I do think we should always be previewing the next layer deep of knowledge. I also think, and evidence like this recent study supports this, that even at the most basic level discussing why is important. People should learn from the youngest age that facts and concepts go together, and children seem to have an instinctive yearning for understanding the concepts. This should be nurtured.

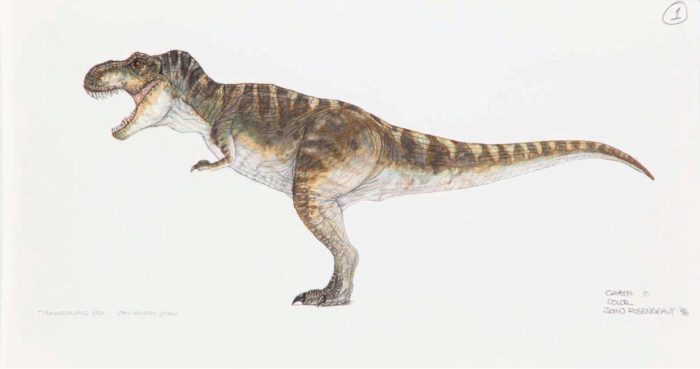

With my own children I also went further, and addressed from the youngest age the “how do we know” layer. When my daughter asked me what color dinosaurs were, I asked her back, “How could we know what color they were?” We then explored that question together. Inference from extant animals, for example. What factors determine what color an animal is. Camouflage is a big factor, but not all animals are camouflages. Some are brightly colored to attract mates, or as a warning that they are venomous or poisonous. So we may be able to infer what some dinosaurs likely looked like by understanding their likely behavior. Predators, for example, were likely camouflaged – but like tigers, this can take many forms. Some fossils also retain fossilized pigments, so we do have some direct evidence, mostly from avian dinosaurs.

Even from the youngest age, asking, “how do we know” was much more engaging and interesting than simply giving an answer, even a causal one. I look at this as – give me a fish and you feed me for a day, teach me to fish and you feed me for life. Give someone a fact, and they have learned one thing. Teach them how to learn, how science and knowledge work, and how to think critically, and you give them the universe.