Apr

01

2024

I have not written before about Havana Syndrome, mostly because I have not been able to come to any strong conclusions about it. In 2016 there was a cluster of strange neurological symptoms among people working at the US Embassy in Havana, Cuba. They would suddenly experience headaches, ringing in the ears, vertigo, blurry vision, nausea, and cognitive symptoms. Some reported loud whistles, buzzing or grinding noise, usually at night while they were in bed. Perhaps most significantly, some people who reported these symptoms claim that there was a specific location sensitivity – the symptoms would stop if they left the room they were in and resume if they returned to that room.

These reports lead to what is popularly called “Havana Syndrome”, and the US government calls “anomalous health incidents” (AHIs). Eventually diplomats in other countries also reported similar AHIs. Havana Syndrome, however, remains a mystery. In trying to understand the phenomenon I see two reasonable narratives or hypotheses that can be invoked to make sense of all the data we have. I don’t think we have enough information to definitely reject either narrative, and each has its advocates.

One narrative is that Havana Syndrome is caused by a weapon, thought to be a directed pulsed electromagnetic or acoustic device, used by our adversaries to disrupt American and Canadian diplomats and military personnel. The other is that Havana Syndrome is nothing more than preexisting conditions or subjective symptoms caused by stress or perhaps environmental factors. All it would take is a cluster of diplomats with new onset migraines, for example, to create the belief in Havana Syndrome, which then takes on a life of its own.

Both hypotheses are at least plausible. Neither can be rejected based on basic science as impossible, and I would be cautious about rejecting either based on our preexisting biases or which narrative feels more satisfying. For a skeptic, the notion that this is all some kind of mass delusion is a very compelling explanation, and it may be true. If this turns out to be the case it would definitely be satisfying, and we can add Havana Syndrome to the list of historical mass delusions and those of us who lecture on skeptical topics can all add a slide to our Powerpoint presentations detailing this incident.

Continue Reading »

Mar

01

2024

When I use my virtual reality gear I do practical zero virtual walking – meaning that I don’t have my avatar walk while I am not walking. I general play standing up which means I can move around the space in my office mapped by my VR software – so I am physically walking to move in the game. If I need to move beyond the limits of my physical space, I teleport – point to where I want to go and instantly move there. The reason for this is that virtual walking creates severe motion sickness for me, especially if there is even the slightest up and down movement.

When I use my virtual reality gear I do practical zero virtual walking – meaning that I don’t have my avatar walk while I am not walking. I general play standing up which means I can move around the space in my office mapped by my VR software – so I am physically walking to move in the game. If I need to move beyond the limits of my physical space, I teleport – point to where I want to go and instantly move there. The reason for this is that virtual walking creates severe motion sickness for me, especially if there is even the slightest up and down movement.

But researchers are working on ways to make virtual walking a more compelling, realistic, and less nausea-inducing experience. A team from the Toyohashi University of Technology and the University of Tokyo studied virtual walking and introduced two new variables – they added a shadow to the avatar, and they added vibration sensation to the feet. An avatar is a virtual representation of the user in the virtual space. Most applications allow some level of user control over how the avatar is viewed, but typically either first person (you are looking through the avatar’s eyes) or third person (typically your perspective is floating above and behind the avatar). In this study they used only first person perspective, which makes sense since they were trying to see how realistic an experience they can create.

The shadow was always placed in front of the avatar and moved with the avatar. This may seem like a little thing, but it provides visual feedback connecting the desired movements of the user with the movements of the avatar. As weird as this sounds, this is often all that it takes to not only feel as if the user controls the avatar but is embodied within the avatar. (More on this below.) Also they added four pads to the bottom of the feet, two on each foot, on the toe-pad and the heel. These vibrated in coordination with the virtual avatar’s foot strikes. How did these two types of sensory feedback affect user perception?

Continue Reading »

Dec

12

2023

Scientists have developed virtual reality goggles for mice. Why would they do this? For research. The fact that it’s also adorable is just a side effect.

Scientists have developed virtual reality goggles for mice. Why would they do this? For research. The fact that it’s also adorable is just a side effect.

One type of neuroscience research is to expose mice in a laboratory setting to specific tasks or stimuli while recording their brain activity. You can have an implant, for example, measure brain activity while it runs a maze. However, having the mouse run around an environment puts limits on the kind of real time brain scanning you can do. So researchers have been using VR (virtual reality) for about 15 years to simulate an environment while keeping the mouse in a more controlled setting, allowing for better brain imaging.

However, this setup is also limiting. The VR is really just surrounding wrap-around screens. But it is technically challenging to have overhead screens, because that is where the scanning equipment is, and there are still visual clues that the mouse is in a lab, not the virtual environment. So this is an imperfect setup. k

The solution was to build tiny VR goggles for mice. The mouse does not wear the goggles like a human wears a VR headset. They can’t get them that small yet. Rather, the goggles are mounted, and the mouse is essentially placed inside the goggle while standing on a treadmill. The mouse can therefore run around while remaining stationary on the treadmill, and keep his head in the mounted VR goggles. This has several advantages over existing setups.

Continue Reading »

Dec

01

2023

Let’s dive head first into one of the internet’s most contentious questions – do we have true free will? This comes up not infrequently whenever I write here about neuroscience, most recently when I wrote about hunger circuitry, because the notion of the brain as a physical machine tends to challenge our illusion of complete free will. Debates tend to become heated, because it is truly challenging to wrap our meat brains around such an abstract question.

Let’s dive head first into one of the internet’s most contentious questions – do we have true free will? This comes up not infrequently whenever I write here about neuroscience, most recently when I wrote about hunger circuitry, because the notion of the brain as a physical machine tends to challenge our illusion of complete free will. Debates tend to become heated, because it is truly challenging to wrap our meat brains around such an abstract question.

I always find the discussion to be enlightening, however. In the most recent discussion I detect that some commenters are using the term “free will” differently than others. Precisely (operationally) defining terms is always critical in such discussions, so I wanted to break down what I feel are the three definitions or levels of free will that we are dealing with. It seems to me that there is a superficial level, a neurological level, and a metaphysical level to free will. Language fails us here because we have only one term to refer to these very different things (at least colloquially – philosophers probably have lots of highly precise technical terms).

At the most superficial level we do make decisions, and some people consider this free will. To be clear, I am not aware of any serious thinker or philosopher who holds that we do not make decisions. There is a deeper discussion about the mechanisms of those decisions, but we do make them, we are consciously aware of them, and we can act on them. From this perspective, people are agents, and are accountable to the choices they make.

Continue Reading »

Nov

27

2023

There are several technologies which seem likely to be transformative in the coming decades. Genetic bioengineering gives us the ability to control the basic machinery of life, including ourselves. Artificial intelligence is a suite of active, learning, information tools. Robotics continues its steady advance, and is increasingly reaching into the micro-scale. The world is becoming more and more digital, based upon information, and our ability to translate that information into physical reality is also increasing.

There are several technologies which seem likely to be transformative in the coming decades. Genetic bioengineering gives us the ability to control the basic machinery of life, including ourselves. Artificial intelligence is a suite of active, learning, information tools. Robotics continues its steady advance, and is increasingly reaching into the micro-scale. The world is becoming more and more digital, based upon information, and our ability to translate that information into physical reality is also increasing.

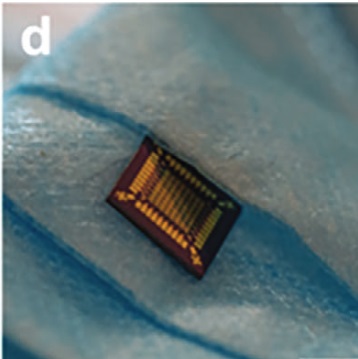

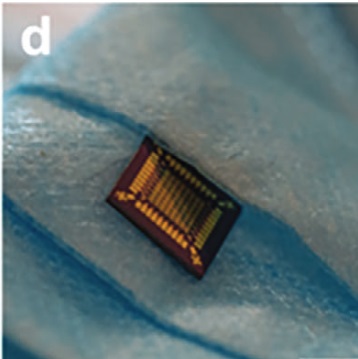

Finally, we are increasingly able to interface ourselves with this digital technology, through brain machine interfaces, and hybrid biological technology. This is the piece I want to discuss today, because of a recent paper detailing a hybrid biopolymer transistor. This is one of the goals of computer technology going forward – to make biological, or at least biocompatible, computers. The more biocompatible our digital technology, the better we will be able to interface that technology with biology, especially the human brain.

This begins with the transistor, the centerpiece of modern computing technology. A transistor is basically a switch that has two states, which can be used to store binary information (1s and 0s). If the switch in on, current flows through the semiconductor, and that indicates a 1, if it is off, current does not flow, indicating a zero. The switch is also controlled by a gate separated by an insulator. These switches can turn on and off 100 billion times a second. Circuits of these switches are designed to process information – to do the operations that form the basis of computing. (This is an oversimplification, but this is the basic idea.)\

This new hybrid transistor uses silk proteins as the insulator around the gates of the transistor. The innovation is the ability to control these proteins at the nano-scale necessary to make a modern transistor. Using silk proteins rather than an inorganic substance allows the transistor to react to its environment in a way that purely inorganic transistors cannot. For example, the ambient moisture will affect the insulating properties of these proteins, changing the operation of the gates.

Continue Reading »

Nov

20

2023

One of the organizing principles that govern living organisms is homeostasis. This is a key feature of being alive – maintaining homeostatic equilibrium both internally and externally. Homeostatic systems usually involve multiple feedback loops that maintain some physiological parameter within an acceptable range. For example, our bodies maintain a very narrow temperature range, our blood has a very narrow range for pH, salt content, CO2 concentration, oxygen levels, and many other parameters. Each cell maintains specific concentrations of many electrolytes across their membranes. Organisms maintain the proper amount of total fluid – too much and their tissue becomes edematous and the heart is overworked, too little and they cannot maintain blood pressure or tissue function.

One of the organizing principles that govern living organisms is homeostasis. This is a key feature of being alive – maintaining homeostatic equilibrium both internally and externally. Homeostatic systems usually involve multiple feedback loops that maintain some physiological parameter within an acceptable range. For example, our bodies maintain a very narrow temperature range, our blood has a very narrow range for pH, salt content, CO2 concentration, oxygen levels, and many other parameters. Each cell maintains specific concentrations of many electrolytes across their membranes. Organisms maintain the proper amount of total fluid – too much and their tissue becomes edematous and the heart is overworked, too little and they cannot maintain blood pressure or tissue function.

Some of these homeostatic feedback loops are purely physiological, happening at a cellular, tissue, or organ level. You don’t have to think about the pH of your blood. It can manage itself. But many involve behavior as part of the homeostatic system. If you are dehydrated you get thirsty and seek out water. If you are cold you bundle up and seek warmth. If your body requires nutrients you get hungry and eat.

That last one, hunger and eating, turns out to be very tricky. First, this is mostly a behaviorally driven homeostatic system – how much do we eat, what do we eat, when do we eat, and how physically active are we (combined with many metabolic factors). Second, this behavioral homeostatic system is very context dependent. The system anticipates future needs and future conditions, not just our body’s needs in the moment. It also appears that behavior driven by a homeostatic imperative can be extremely powerful. Think about how motivated you get to find water when you are extremely thirsty.

Continue Reading »

Sep

12

2023

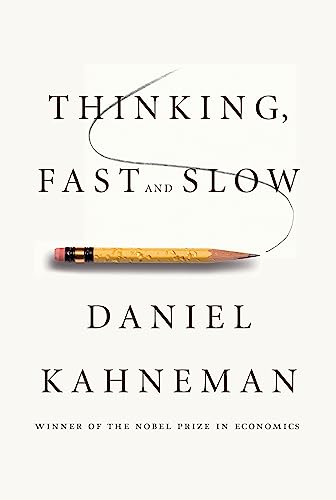

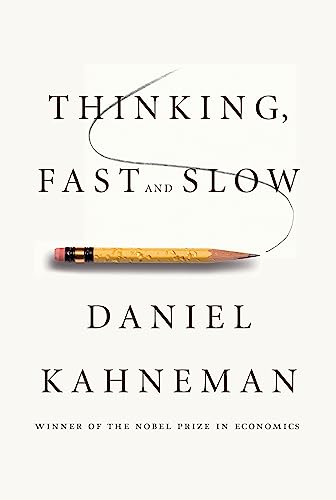

Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.)

Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.)

This problem is the basis of a large psychological literature on thinking systems in the human brain, discussed in Daniel Kahneman’s book: Thinking, Fast and Slow. The idea is that there are two parallel thinking systems in the brain, a fast intuitive system that provides quick answers which may or may not be strictly true, and a slow analytical system that will go through a problem systematically and check the results.

This basic scheme is fairly well established in the research literature, but there are many sub-questions. For example – what is the exact nature of the intuition for any particular problem? What is the interaction between the fast and slow system? What if multiple intuitions come into conflict by giving different answers to the same problem? Is it really accurate to portray these different thinking styles as distinct systems? Perhaps we should consider them subsystems, since they are ultimately part of the same singular mind. Do they function like subroutines in a computer program? How can we influence the operations or interaction of these subroutines with prompting?

A recent publication present multiple studies with many subjects addressing these subquestions. If you are interested in this question I suggest reading the original article in full. It is fairly accessible. But here is my overview. Continue Reading »

Sep

11

2023

I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a supertaster, and the taste of alcohol to me is horrible – it overwhelms any other potential flavors in the drink. But I am also not judgmental. I understand that most people who consume alcohol do so in moderation without demonstrable ill effects. I also know I am in the minority when it comes to taste.

I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a supertaster, and the taste of alcohol to me is horrible – it overwhelms any other potential flavors in the drink. But I am also not judgmental. I understand that most people who consume alcohol do so in moderation without demonstrable ill effects. I also know I am in the minority when it comes to taste.

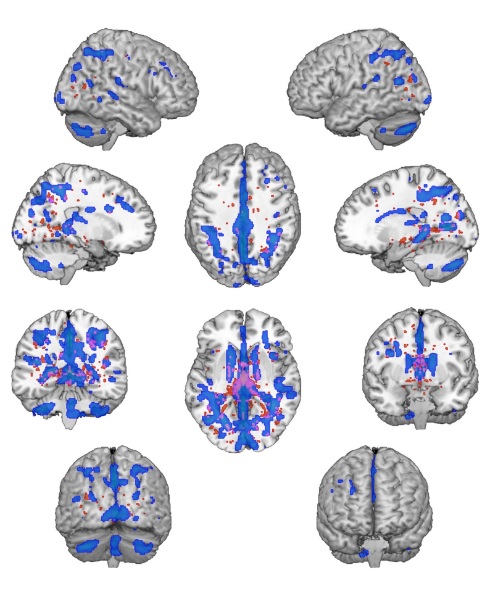

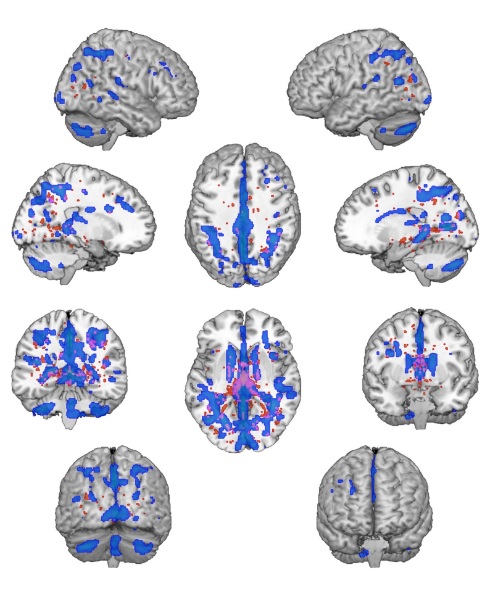

But we do need to recognize that alcohol, like many other substances of abuse like cocaine, has the ability to be addictive, and can result in alcohol use disorder. Excessive alcohol use costs the US economy $249 billion per year from health care costs, lost productivity, traffic accidents, and criminal justice system costs. It dwarfs all other addictive substances combined. It is also well established that long term, excessive alcohol use reduces cognitive function.

Recent research has explored the question of exactly what the effects of addictive substances are on the brain with chronic use. One of the primary effects appears to be on cognitive flexibility. In general terms this neurological function is exactly what it sounds like – flexibility in thinking and behavior. But researchers always need a way to operationalize such concepts – how do we measure it? There are two basic ways to operationalize cognitive flexibility – set shifting and task switching. Set shifting involves change the rules of how to accomplish a task, while task switching involves changes to a different task altogether.

For example, a task switching test might involve sorting objects that are of different shapes, colors, textures, and sizes. First subjects may be told to sort by colors, but also they are to respond to a specific cue (such as a light going on) by switching to sorting by shape. The test is – how quickly and effectively can a subject switch tasks like this? How many sorting mistakes will they make after switching tasks? Set shifting, on the other hand, changes the rules rather than the task – push the button every time the red light comes on, vs the green light.

Continue Reading »

Sep

08

2023

There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons.

There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons.

Let’s consider gift-giving, for example. Culture and intuition provide several answers as to what constitutes a good gift, which we can define as the level of gratitude and resulting happiness on the part of the gift recipient. We can also consider a secondary, but probably most important, outcome – the effect on the relationship between the giver and receiver. There is also the secondary effect of the satisfaction of the gift giver, which depends largely on the gratitude expressed by the receiver.

When considering what makes a good gift, people tend to focus on a few variables, reinforced by cultural expectations – the gift should be a surprise, it should provoke a big reaction, it should be unique, and more expensive gifts should evoke more gratitude. But it turns out, none of these things are true.

A recent study, for example, tried to simulate prior expectations on gift giving and found no significant effect on gratitude. These kinds of studies are all constructs, but there is a pretty consistent signal in the research that surprise is not an important factor to gift-giving. In fact, it’s a setup for failure. The gift giver has raised expectations of gratitude because of the surprise factor, and is therefore likely to be disappointed. The gift-receiver is also less likely to experience happiness from receiving the gift if the surprise comes at the expense of not getting what they really want. You would be far better off just asking the person what they want, or giving them something you know that they want and value rather than rolling the dice with a surprise. To be clear, the surprise factor itself is not a negative, it’s just not really a positive and is a risk.

Continue Reading »

Sep

05

2023

Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.

Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.

Often people will resort to the “availability heuristic” when confronted with these types of claims. If they can readily think of an example that seems to support the claim, then they accept it as probably true. We use the availability of an example as a proxy for data, but it’s a very bad proxy. What we really need to address such questions is often statistics, something which is not very intuitive for most people.

Of course, that’s where science comes in. Science is a formal system we use to supplement our intuition, to come to more reliable conclusions about the nature of reality. Recently researchers published a very large review of data, a meta-analysis, combined with a new data analysis to address this very question. First, we need operationalize the question, to put it in a form that is precise and amenable to objective data. If we look at couples, how similar or different are they? To get even more precise, we need to identify specific traits that can be measured or quantified in some way and compare them.

Continue Reading »

When I use my virtual reality gear I do practical zero virtual walking – meaning that I don’t have my avatar walk while I am not walking. I general play standing up which means I can move around the space in my office mapped by my VR software – so I am physically walking to move in the game. If I need to move beyond the limits of my physical space, I teleport – point to where I want to go and instantly move there. The reason for this is that virtual walking creates severe motion sickness for me, especially if there is even the slightest up and down movement.

When I use my virtual reality gear I do practical zero virtual walking – meaning that I don’t have my avatar walk while I am not walking. I general play standing up which means I can move around the space in my office mapped by my VR software – so I am physically walking to move in the game. If I need to move beyond the limits of my physical space, I teleport – point to where I want to go and instantly move there. The reason for this is that virtual walking creates severe motion sickness for me, especially if there is even the slightest up and down movement. Scientists have developed

Scientists have developed  Let’s dive head first into one of the internet’s most contentious questions – do we have true free will? This comes up not infrequently whenever I write here about neuroscience, most recently when

Let’s dive head first into one of the internet’s most contentious questions – do we have true free will? This comes up not infrequently whenever I write here about neuroscience, most recently when  There are several technologies which seem likely to be transformative in the coming decades. Genetic bioengineering gives us the ability to control the basic machinery of life, including ourselves. Artificial intelligence is a suite of active, learning, information tools. Robotics continues its steady advance, and is increasingly reaching into the micro-scale. The world is becoming more and more digital, based upon information, and our ability to translate that information into physical reality is also increasing.

There are several technologies which seem likely to be transformative in the coming decades. Genetic bioengineering gives us the ability to control the basic machinery of life, including ourselves. Artificial intelligence is a suite of active, learning, information tools. Robotics continues its steady advance, and is increasingly reaching into the micro-scale. The world is becoming more and more digital, based upon information, and our ability to translate that information into physical reality is also increasing. One of the organizing principles that govern living organisms is homeostasis. This is a key feature of being alive – maintaining homeostatic equilibrium both internally and externally. Homeostatic systems usually involve multiple feedback loops that maintain some physiological parameter within an acceptable range. For example, our bodies maintain a very narrow temperature range, our blood has a very narrow range for pH, salt content, CO2 concentration, oxygen levels, and many other parameters. Each cell maintains specific concentrations of many electrolytes across their membranes. Organisms maintain the proper amount of total fluid – too much and their tissue becomes edematous and the heart is overworked, too little and they cannot maintain blood pressure or tissue function.

One of the organizing principles that govern living organisms is homeostasis. This is a key feature of being alive – maintaining homeostatic equilibrium both internally and externally. Homeostatic systems usually involve multiple feedback loops that maintain some physiological parameter within an acceptable range. For example, our bodies maintain a very narrow temperature range, our blood has a very narrow range for pH, salt content, CO2 concentration, oxygen levels, and many other parameters. Each cell maintains specific concentrations of many electrolytes across their membranes. Organisms maintain the proper amount of total fluid – too much and their tissue becomes edematous and the heart is overworked, too little and they cannot maintain blood pressure or tissue function. Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.)

Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.) I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a

I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a  There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons.

There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons. Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.

Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.