Jul 01 2016

TIME Gets It Wrong on Acupuncture

A recent Time Magazine article tries to answer the question: Does Acupunture Work? Their answer:

A recent Time Magazine article tries to answer the question: Does Acupunture Work? Their answer:

For certain conditions—particularly pain—there’s evidence it works. Exactly how it works is an open question.

This answer is wrong. Granted, this is a deceptively complex question and there is a tremendous amount of authoritative misinformation out there, so it is hard to blame a journalist for getting this one wrong.

Perhaps the biggest pitfall in science journalism is the problem of outlier or non-representative experts. A journalist talks to someone who has appropriate credentials, but whose opinion on a topic is either a minority opinion, or just one side of a legitimate controversy. The journalist then mistakes this one person’s opinion for the consensus scientific opinion.

In this the author, Markham Heid, spoke to an acupuncturist, a pro-acupuncture researcher, and Andrew Vickers. Vickers is a statistician who co-authored a 2012 meta-analysis of acupuncture. Myself, Edzard Ernst, David Gorski and others sharply criticized this meta-analysis.

Here is the quick overview – Vickers and his coauthors conducted a meta-analysis of acupuncture studies in which they included blinded and unblinded studies. They found statistically significant effects, and this was widely reported in the lay media.

We have many technical criticisms for the study, but the two big criticisms amount to this: The results were clearly not clinically significant, and such a tiny effect size could likely be explained by bias in the research.

The results showed a difference of 5 points on a pain scale of 0-100. Other trials have directly evaluated where the threshold is for minimal clinical significance, which means a level of pain difference that a typical patient can perceive. That minimal clinical significance comes in between 15-20, which means that a difference of 5 points is clearly not even minimally clinically significant.

Vickers and I simply disagree on how to interpret this data. Vickers is making the classic frequentist fallacy – if I can get over the magic p-value of 0.05, then the alleged effect is real. This approach does not adequately account for publication bias, researcher bias, p-hacking, and methodological weaknesses like poor or no blinding. Acupuncture research has a particular problem with poor blinding, and cultural bias. Nearly 100% of acupuncture studies coming out of China are positive, for example. If this is not accounted for, the research data is tainted.

Doing a meta-analysis and coming up with a single number of statistical significance does not really capture the entirety of the scientific research. We need to look at the relationship between rigor and effect size. Almost all treatments display a decline effect – the better the research, the smaller the effect. Some effects decline to a smaller but stable and replicable effect. Others decline to zero for the most rigorous studies.

Acupuncture effects decline to zero. Acupuncture effects are not real. Acupuncture is an elaborate placebo.

Heid clearly did not speak to anyone critical of acupuncture, and this was a fatal flaw in their reporting, leading them to the wrong conclusion.

Heid quoted credulously from an acupuncturist without a hint of skepticism:

A typical visit to an acupuncturist might begin with an examination of your tongue, the taking of your pulse at several points on each wrist and a probing of your abdomen. “They didn’t have MRIs or X-rays 2,500 years ago, so they had to use other means to assess what’s going on with you internally,” says Stephanie Tyiska, a Philadelphia-based acupuncture practitioner and instructor.

Tongue diagnosis is pure pseudoscience, as is pulse diagnosis. They are little more than medical cold-readings, like iridology. In Medieval Europe doctors would essentially do the same thing, using elaborate charts of the exact color of a patient’s urine. These elaborate but ultimately meaningless systems proliferated in pre-scientific cultures, where complexity and detail substituted for actual understanding.

Completing the typical acupuncture triad, Heid quotes from Vitaly Napadow:

Many people equate placebo effects with scams. “The term placebo has always had this very negative connotation,” says Vitaly Napadow, director of the Center for Integrative Pain Neuroimaging at Harvard Medical School. But Napadow says our poor opinion of placebo needs revising.

No, it doesn’t. Placebo effects are mostly illusions, they are brief and subjective. They do not justify abject pseudoscience passing itself off as medicine.

In addition to the placebo gambit, Napadow plays another common game in which transient non-specific physiological responses to local trauma are sold as “how acupuncture might work.” Sure, there are compensatory mechanisms to local trauma, as you might expect. This does not necessarily justify the local trauma.

The problem with research like Napadow’s is that they assume acupuncture works, when it doesn’t. Any effect seen can be spun into a possible mechanism, but they can never show that it is a meaningful mechanisms – because in order to do this they would need to correlate it with acupuncture working, but acupuncture does not work. Research based on a false premise tends not to be very fruitful.

Conclusion

Acupuncture does not work. The totality of scientific research has produced several clear results: it does not matter where you stick the needles, it does not matter if you stick the needles, and acupuncture points have no basis in reality.

Acupuncture is an elaborate placebo, whose effects are not even clinically significant, which even Vickers’ own data clearly shows.

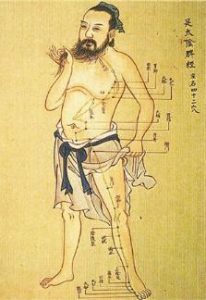

Worse, acupuncture comes with vast cultural baggage. It is part of Traditional Chinese Medicine, which is an entire system of ancient medical pseudoscience with some not-so-ancient modern fakes passing themselves off as ancient Chinese medicine.

For many practitioners treating subjective symptoms is just the foot in the door. Once in they will try to treat serious illnesses with “medical acupuncture.”

Unfortunately Heid, like many other journalists, got the bottom line wrong and has now contributed to the public misunderstanding of this topic.