Dec 16 2014

Neurosurgeon Thinks the Brain Doesn’t Store Memories

It has been six years since I have written a blog post deconstructing the nonsense of our favorite creationist neurosurgeon, Michael Egnor. In case you have forgotten, he is a dualist writing for the intelligent design propaganda blog, Evolution News and Views. He delights in ridiculing what he calls “materialist metaphysics,” or what scientists call, “science.”

It has been six years since I have written a blog post deconstructing the nonsense of our favorite creationist neurosurgeon, Michael Egnor. In case you have forgotten, he is a dualist writing for the intelligent design propaganda blog, Evolution News and Views. He delights in ridiculing what he calls “materialist metaphysics,” or what scientists call, “science.”

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that he has managed to outdo his prior incoherent ramblings. In a recent blog post he claims that it is impossible for the brain to store memories, an idea he ridicules as “nonsense.”

As usual, Egnor is playing loose with definitions and logic, tying himself up in a conceptual knot in order to arrive at his desired destination – the idea that the brain cannot account for mental phenomena. His logic train derails pretty quickly:

It has been known for the better part of a century that certain structures in the brain are associated with memory. The amygdala and the hippocampus in the temporal lobe, and some adjacent cortical regions, have been shown to be associated with the act of remembering in animals and humans.

Notice the term “associated” – memory is just “associated” with specific brain regions. Egnor is desperately trying to deny that the association is causal. Similarly he admits that such brain regions are “necessary” for memory, but then insists (without evidence) that they are insufficient.

He is playing the same game of neuroscience denial he has for years – dismiss all of the evidence that the brain is responsible for mental function, such as memory, by minimizing it as mere correlation or association. He thinks the brain is somehow involved in these things, but cannot do them on its own. Something else is required.

To make that case, that the brain is insufficient, he dives deeply into his main bit of illogic.

It’s helpful to begin by considering what memory is — memory is retained knowledge. Knowledge is the set of true propositions. Note that neither memory nor knowledge nor propositions are inherently physical. They are psychological entities, not physical things. Certainly memories aren’t little packets of protein or lipid stuffed into a handy gyrus, ready for retrieval when needed for the math quiz.

When making scientific or philosophical arguments, clear and precise definitions are critical. Often pseudoscientists will give themselves enough wiggle room with vague or ambiguous definitions in order to do a little logical sleight of hand. Egnor is sloppy, to say the least, with his definitions.

I would not define memory as “retained knowledge.” The term “knowledge” is too ambiguous. Also, note that he uses “retained” as if it is any different than “stored.” He goes on to define knowledge as a set of true propositions, which should immediately strike you as a massively insufficient definition for what memory “retains.”

Memories don’t have to be true, and they don’t have to be propositions. You can remember an image, a sound, an idea (true or false), an association, a feeling, facts, and skills, including specific motor tasks.

A far more accurate an useful definition of memory would be stored information. That would not serve Egnor’s purposes well, however. He uses the more vague “retained knowledge” hoping you won’t notice what memories actually are – information.

By pointing out that memories are information the analogy to computers becomes obvious. A hard drive of a computer stores information also. Computer information is stored physically, in the pits on a CD, or magnetic properties of a tape or disk, for example. That information can be used to construct an image, music, a word processor document, or a computer program.

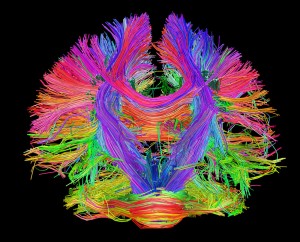

Can the brain store information? Of course it can. The average adult human brain has about 87 billion neurons. Those neurons make connections to other neurons through axons and dendrites. The number, pattern, and strength of those functional connections is information – about 100 trillion connections, with an estimated memory capacity of 2.5 petabytes (million gigabytes).

The brain’s structure and function seems to be for the very purpose of storing and processing information. The claim that it doesn’t, and can’t, store memories is remarkable, to say the least. A memory, despite Egnor’s insistence, is not a “psychological thing” (which he doesn’t even define). Memory is information which is physical.

The train is now flying off the tracks, but let’s watch it crash into the ravine:

Now you may believe — as most neuroscientists and too many philosophers (who should know better) mistakenly believe — that although of course memories aren’t “stored” in brain tissue per se, engrams of memories are stored in the brain, and are retrieved when we remember the knowledge encoded in the engram. Indeed neuroscientists believe that they have found things in the brain very much like engrams of some sort, that encode a memory like a code encodes a message.

You will notice that Egnor does not define “engram,” even though it seems to be the linchpin of his current argument. Perhaps that’s because it really adds nothing to the issue. An engram is an outdated term for the physical substance of a memory in the brain.

Functionally speaking, the engram is the memory. Egnor pretends that they are somehow different, as if “obviously” a memory cannot be stored, but an engram can. It seems that he is making a dualist assumption here, simply assuming and asserting the entire point of his article – that memories and engrams are different types of things.

Finally, the train explodes:

But there is a real problem with that view. As you try to remember Nana’s face, you must then locate the engram of the memory, which of course requires that you (unconsciously) must remember where in your brain Nana’s face engram is stored — was it the superior temporal gyrus or the middle temporal gyrus? Was it the left temporal lobe or the right temporal lobe? So this retrieval of the Nana memory via the engram requires another memory (call it the “Nana engram location memory”), which must itself be encoded somewhere in your brain. To access the memory for the location of the engram of Nana, you must access a memory for the engram for the location for the engram of Nana. And obviously you must first remember the location of the Nana engram location memory, which presupposes another engram whose location must be remembered. Ad infinitum.

This argument represents such a profound ignorance and misunderstanding of our current knowledge of neuroscience it’s frightening to be coming from anyone, let alone a neurosurgeon.

The brain is a massive parallel processor that stores information in overlapping patterns of neuronal connections. Single neurons can participate in many different memories and processes. This is exactly why our brains are so good at pattern recognition, why one thought or memory reminds you of another, why an odor can trigger a flood of memories, etc.

You don’t have to know (nor does your brain) where in your physical brain a memory is located, because you can access that memory simply because it is integrated with so many other memories.

Next Egnor goes for a typical denialist strategy – we don’t currently know everything, therefore I can pretend we know nothing:

To assert that memories are stored in the brain is gibberish. And don’t fall for the materialist invocation of promissory materialism — “It’s just a limitation of our current scientific knowledge, and we promise that science will solve the problem in due time.” The assertion that the brain stores memories is logical nonsense that doesn’t even rise to the level of empirical testability.

Current scientific understanding is always incomplete. However, our understanding of neuroscience is fairly robust and growing steadily. There is no single source that lays out all of the scientific research on memory, but here is one review that goes over a few mechanisms.

Egnor has the nerve to invoke logic and empiricism with respect to modern neuroscience. This is a strategy I have noticed quite a bit among the science deniers – just keep parroting the language of science and skepticism and accusing others of being guilty of your sins.

Returning to his old nonsense, he writes:

How then, you reasonably ask, can we explain the obvious dependence of memory on brain structure and function? While it is obvious that the memories aren’t stored, it does seem that some parts of the brain are necessary ordinarily for memory. And that’s certainly true. But necessary does not mean sufficient.

The obvious dependence of memory on brain structure and function is most easily explained by that brain structure and function being memory. Egnor has put forward no argument against that elegant solution. There is also absolutely no reason not to conclude that the brain is sufficient to explain memory, Egnor simply does not wish it to be so, hence his convoluted poor logic and misdirection.

In fact, we are getting better and better at manipulating memory, not just in humans but in many experimental animals, by manipulating neurons, their connections, and their function. There does not seem to be any limit to this, consistent with the theory that memories are entirely brain function.

Finally we get to Egnor’s brief position:

I hew to Thomistic dualism, which is a coherent view of the mind that takes an Aristotelian perspective and for which the participation of the brain in memory is not problematic at all.

After spending paragraphs unsuccessfully trying to undermine modern neuroscience, Egnor attempts to replace it with a single paragraph. He makes no attempt to establish that his alternate is logically consistent, or that it can be tested empirically. That is the double standard of denialism – hold the denied science to ever higher standards (whatever it takes) in order to cast doubt on the conclusions, then magically substitute your own position without any requirement for logic or evidence.

Thomistic dualism is just another flavor of dualistic nonsense, the notion that there are two kinds of stuff, material stuff and spiritual stuff. Egnor’s preferred version actually solves nothing, it simply asserts that the soul and the material body work together. (OK, problem solved, I guess.)

Conclusion

Egnor is playing word and logic games, not making a serious analysis of the science of memory. In fact, he appears to be largely ignorant of the neuroscience. He uses vague terms in a confusing way (reflecting his sloppy thinking) to force his desired conclusions.

If you are going to write a single essay attempting to refute and entire discipline of science as obvious nonsense, you’re going to have to do much better than Egnor can muster.

Once again, he has just reminded us of the true meaning of “Egnorance.”