Apr 22 2016

Illegal Immigration and the Law of Unintended Consequences

One thing I have learned as a science communicator over the last two decades, trying to digest many areas of science, is that stuff is complicated. It is a good rule of thumb that everything is more complicated than you might originally think.

One thing I have learned as a science communicator over the last two decades, trying to digest many areas of science, is that stuff is complicated. It is a good rule of thumb that everything is more complicated than you might originally think.

This complexity takes various forms. First, unless you are at the leading edge of expertise in an area, your understanding of that topic is relatively superficial. There is greater depth and nuance than your current understanding, which is likely a necessary simplification.

Second, there are few clean answers in science. Some things, obviously, are well established to the point that we can treat them as facts, but many more things than we might naively suppose are controversial on some level. The evidence is mixed, imperfect, and incomplete and there remain various opinions about how to interpret the data.

As an aside, this is one of my peeves about how science is often communicated. A complex debate is distilled down to, scientists think X (representing just one side of that debate). Each time a new study is published apparently supporting one position, that position is now correct and the others are now wrong. All the nuance is lost.

We talk about this phenomenon this week on the SGU, referencing a new study about dinosaur fossil frequencies resulting in this headline: Dinosaurs weren’t driven to extinction by that meteorite after all. Well, yes they were. The study just shows that some dinosaur subclades were in decline prior to the impact. The article is written (the headline is much worse) as if this one piece of evidence settles the debate entirely in one direction. The real story is more complex, and more interesting, and more accurately reflects how science actually works.

A third type of complexity is that which results from the complex interactions within a system that has many moving parts, i.e. most things in the universe. Biological systems are complex, as are sociological systems, for example. Tugging on one strand in the complex web of interrelationships often results in outcomes that are different than one might initially think – outcomes that are counterintuitive and even unintended. This is what we mean by the law of unintended consequences.

Undocumented Immigrants

A new paper demonstrates this principle with respect to border control along the southern border between Mexico and the US. The paper is partly observational and partly theoretical. I don’t have the background to evaluate the technical details of their analysis, and I have not yet seen any analysis or response from other experts. So, for now let’s take the paper at face value with the understanding that its conclusions are tentative and I am not saying they are definitively true.

The authors, Douglas S. Massey and Karen A. Pren from Princeton University, make a very interesting argument, which does seem entirely reasonable. They argue that the simplistic approach to border control involved increasing border security in order to reduce the flow of undocumented immigrants from Mexico.

“From 1986 to 2010, the United States spent $35 billion on border enforcement and the net rate of undocumented population growth doubled.”

They further argue this was not simply a failure of insufficient border enforcement, but actually a result of it. Their position is a great example of unintended consequences resulting from not considering the impact of an intervention on the entire system.

What increased border security does is raise the cost of crossing the border. Motivated people still find a way across, but it is more expensive and dangerous. Therefore, the benefits of crossing have to be greater in order to justify the higher expense.

Most undocumented immigrants were coming across as laborers. They would enter the country mostly to work as laborers in three states, and when they made sufficient money they would return home. Increasing border security, however, meant they would need to stay longer and make more money to pay for the higher expense of border crossing.

In other words, increasing border security did not keep undocumented immigrants out, it kept them in. This changed the dynamic from one in which there was a circular flow of migrant workers into and out of the US from Mexico to one where migrants came to the US and stayed, because they could not risk or afford another border crossing to get home. Staying in the US longer also meant that more migrants were having children in the US.

They argue that if the US had simply done nothing over that same time period (kept border security as it was) there would be fewer undocumented immigrants than there are today.

There are other layers to this as well.

“Mass immigration from Mexico has ended and won’t be coming back owing to the decline of Mexican fertility from 6.5 children per woman in the 1960s to around 2.2 children per woman today, roughly replacement level,” Massey said. “Labor force growth in Mexico has dropped sharply and Mexico is now becoming an aging society in which fewer and fewer people are in the migration-prone ages of 15-30, so the pressure is off in a demographic sense.”

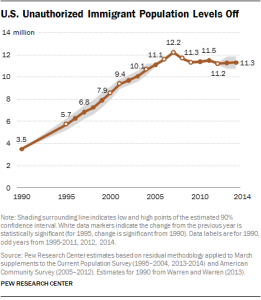

The result of this is that undocumented immigrants peaked in 2007 at 12.2 million. In the last 9 years this number has fallen to about 11.3 million, partly representing a net flow of immigrants from the US back to Mexico. In the last decade at least, tighter border security served, if anything, to maintain undocumented Mexican immigrants in the US.

Massey and Pren argue that we need to move from a policy of immigration control to one of immigration management. We need to look at the whole system, including human behavior. For example, they argue that if the 11.3 million undocumented immigrants were given some form of legal status, many of them would return home, because they would now have the security of knowing that could return to the US whenever they wanted.

Conclusion

I understand that this is a hot political issue, but all the more reason why we should take a deep breath, try to look past the emotions and politics, and take an objective and scientific look at the issue.

Massey and Pren may have an ideological bias of their own (I’m not saying they do, I am just talking about basic principles), which is why any one study cannot be definitive, especially in a complex area such as this. What else I have read on this topic by other scientists is consistent with their overall approach. I will also have to keep an eye out for other experts commenting on this study.

This is also a good example of the frequent disconnect between scientists and politicians. Politics lends itself to simple emotionally appealing answers, while reality does not. Following simplistic and emotionally motivated actions runs a high risk of unintended consequences, such as the “backfire effect” described by Massey and Pren.