Oct 09 2023

Evidence and the Nanny State Part II

In Part I of this post I outlined some basic considerations in deciding how much the state should impose regulations on people and institutions in order to engineer positive outcomes. In the end the best approach, it seems to me, is a balanced one, where we consider the burden of regulations, both individually and cumulatively, compared to the benefit to individuals and society. We also need to consider unintended consequences and perverse incentives – people still need to feel as if they have individual responsibility, for example. It is a complex balancing act. In the end we should use objective evidence to determine what works and what doesn’t, or at least to be clear-eyed about the tradeoffs. In the US we have the benefit of fifty states which can experiment with various regulations, and this can potentially generate a lot of data.

In Part I of this post I outlined some basic considerations in deciding how much the state should impose regulations on people and institutions in order to engineer positive outcomes. In the end the best approach, it seems to me, is a balanced one, where we consider the burden of regulations, both individually and cumulatively, compared to the benefit to individuals and society. We also need to consider unintended consequences and perverse incentives – people still need to feel as if they have individual responsibility, for example. It is a complex balancing act. In the end we should use objective evidence to determine what works and what doesn’t, or at least to be clear-eyed about the tradeoffs. In the US we have the benefit of fifty states which can experiment with various regulations, and this can potentially generate a lot of data.

Let’s take a look first at cigarette smoking regulations and health outcomes. At this point I don’t think I have to spend too much time establishing that smoking has negative health consequences. They have been well-documented in the last century and are not controversial, so we can take that as an established premise. Given that we know smoking is extremely unhealthy, which measures are justified by government in trying to limit smoking? Interestingly, the answer until around the 1980s was – very little. Surgeon General warnings was about it. Smoking in public was accepted (I caught the tail end of smoking in hospitals).

This was always curious to me. Here we have a product which is known to harm and even kill those who use the product as directed. And it’s addictive, which compromises the autonomy of users. It is interesting to think what would happen if a company tried to introduce tobacco smoking as a product today. I doubt it would get past the FDA. But obviously smoking was culturally established before its harmful effects were generally known. I also always thought that the experience of prohibition created a general reluctance to go down that road again. But then data started coming out about the effects of second-hand smoke, and suddenly the calculus shifted. Now we were not just dealing with the interest of the state in protecting citizens from their own behavior, but the state protecting citizens from the choices of other citizens. This is entirely different – you may have a right to slowly kill yourself, but not to slowly kill me. The result was lots of data about smoking regulations.

One factor that you may not think of as a regulation is taxes – the state sometimes taxes a behavior as a mechanism of limiting it (so-called sin taxes). Is there a relationship between state taxes on cigarettes and smoking-related negative health outcomes? Yes. A review going back to the 1970s found a good correlation, but only in certain age groups. The correlation was strongest in teenagers, but also lasted into the 20s. The data looked at smoking rates into adulthood. If you tax cigarettes, this decreases the number of teenagers who pick up smoking for life. Very young smokers, around age 11, were not effected to a statistically significant degree, and people who start smoking as older adults were also not affected. They found that a tax of one dollar decreases smoking rates by 2% (absolute reduction) and smoking-related deaths by 4%.

A more recent study, looking at data from 2000-2009, also found an association, and even showed that increasing taxes correlated with adults quitting, and this spanned across socioeconomic groups. The authors point out, however, that high cigarette taxes disproportionately affect lower income people, but I think this may get things backward. If you are poor, quitting smoking is probably the best way to save money. You are simply eliminated an unneeded expense. We should be pushing this messaging hard.

What about smoking bans? A 2023 systematic review found a significant reduction in cardiovascular and respiratory disease:

Smoke-free legislation was associated with decreased risk of all CVD events (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.86-0.94), RSD events (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.96), hospitalization due to CVD or RSD (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87-0.95), and adverse birth outcomes (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.96).

Those are significant reductions. Smoking bans reduce hospitalizations, which saves money. I don’t know if we have found the optimal balance on smoking – don’t ban it entirely but heavily tax it, restrict locations, ban direct advertising, and promote anti-smoking public messaging – but it seems pretty good overall. Perhaps this can be a template for other behaviors that dramatically affect health.

Let’s turn to something a little different – seatbelt laws. Again, we can start with the premise that seatbelts work. According to the CDC:

Among drivers and front-seat passengers, seat belts reduce the risk of death by 45%, and cut the risk of serious injury by 50%.

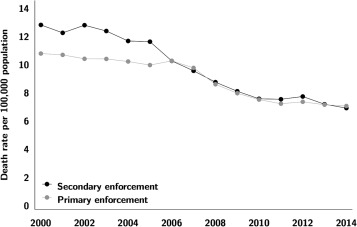

Industry-level regulations seem like a no-brainer – car manufacturers are required to include effective seatbelts in their cars. I am not aware of any pushback against such regulations. The question is, how far should the state go in mandating that drivers wear their seatbelts? There is a range of options from doing nothing other than making them available and perhaps some public messaging to passing laws to require wearing seatbelts or get a fine. But there is also the question of how big a find and how vigorously to enforce seatbelt laws. One main difference among states is whether or not police will pull over drivers simply for not wearing their seatbelt (primary enforcement), or only give them a ticket if they get pulled over for another reason (secondary enforcement).

The data show that seatbelt laws overall save lives. It was also established early on that primary enforcement was more effective than secondary enforcement. However, a more recent study found that the advantage of primary vs secondary enforcement was no longer statistically significant (although there was still a trend). The reason for this is that improvements in airbag design and road safety simply reduced car fatalities overall, so there was less of a statistical benefit to be had. Where does this leave us? Requiring cars have seatbelts and that people use them is clearly effective, and is small enough a regulatory burden that seatbelt laws, combined with aggressive messaging, is a sound tradeoff. The difference between primary and secondary enforcement is less clear as cars have become safer in general, and this is a nuance that can be the focus of reasonable discussion.

These two issues are just a tiny slice of the broader issue of the tradeoffs that sometimes exist between safety regulations and liberty. But they do illustrate the kinds of options available.