Dec 17 2018

Belief in Santa

How old were you, if you ever believed in Santa, when you figured out he was not real? Is belief in Santa benign, beneficial, cruel, or ultimately harmful to the trust children place in adults? Many people have strong opinions about this, but we have little actual data. A recent survey adds some.

How old were you, if you ever believed in Santa, when you figured out he was not real? Is belief in Santa benign, beneficial, cruel, or ultimately harmful to the trust children place in adults? Many people have strong opinions about this, but we have little actual data. A recent survey adds some.

The survey is mainly asking adults about their childhood experiences with belief in Santa, so take that for what’s it’s worth, but here are the main results:

- 34 per cent of people wished that they still believed in Santa with 50 per cent quite content that they no longer believe

- Around 34 per cent of those who took part in the survey said believing in Father Christmas had improved their behaviour as a child whilst 47 per cent found it did not

- The average age when children stopped believing in Father Christmas was 8.

- There are significant differences between England and Scotland –

- The mean age when people stop believing in Father Christmas was 8.03 for England and 8.58 in Scotland.

- There was a difference in attitudes between England and Scotland, as to whether it is ok to lie to children about Santa – more people in Scotland than in England said it was ok to lie to children about Santa.

- A total of 65 per cent of people had played along with the Santa myth, as children, even though they knew it wasn’t true.

- A third of respondents said they had been upset when they discovered Father Christmas wasn’t real, while 15 per cent had felt betrayed by their parents and ten per cent were angry.

- Around 56 per cent of respondents said their trust in adults hadn’t been affected by their belief in Father Christmas, while 30 per cent said it had.

- A total of 31 per cent of parents said they had denied that Santa is not true when directly asked by their child, while 40 per cent hadn’t denied it if they are asked directly.

- A total of 72 per cent of parents are quite happy telling their children about Santa and playing along with the myth, with the rest choosing not to.

This isn’t the first such survey. I found a 1994 survey of 52 children, so smaller sample size but closer to the age in which they discovered Santa was not real. They found:

Fifty-two children who no longer believed in Santa Claus were individually administered a structured interview on their reactions to discovering the truth. Their parents completed a questionnaire assessing their initial encouragement of the child to believe in Santa and rating their child’s reactions to discovering the truth as well as their own reactions to the child’s discovery. Parental encouragement for the child to believe was very strong. Children generally discovered the truth on their own at age seven. Children reported predominantly positive reactions on learning the truth. Parents, however, described themselves as predominantly sad in reaction to their child’s discovery.

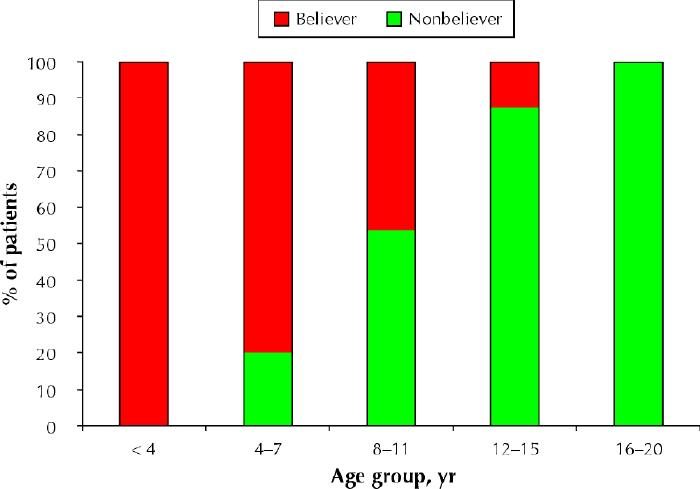

Yet another 2002 survey found that all 4 year-old believe, and no 16 year-olds believe, and belief wanes between those two ages (see the chart at top). There was also a study looking at the expressions of children visiting Santa at a mall:

Four recent informal successive yearly enquiries of the emotions of 1,050 children (total) immediately before their visit with Santa Claus at a shopping mall suggested that about 80% displayed facial expressions, judged by an observer, as indicating indifference. To investigate possible change in emotions of children immediately after their visit with Santa, this study was conducted in 2007. Of the 280 exiting children observed, about 60% appeared to be indifferent.

There does seem to be a paucity of Santa-related research, and most of what we do have is subjective, but does all this tell us anything? In my opinion, it tells us that the stakes are not very high. Sure, children believe in Santa when they are very young. Most work it out for themselves between the ages of 7 and 12 that Santa is not real. Parents seem to enjoy the whole thing more than children.

In my personal opinion, I think belief in Santa is benign overall. Children seem to grow beyond belief in Santa. They don’t feel bad when they cross that threshold to being a non-Santa believer, because they realize that belief in Santa is something for young children, and they are no longer young. The belief evolves as the child evolves, and it all works itself out.

The core controversy, however, is something I discussed in 2016, responding to a Lancet commentary on the topic – does encouraging belief in Santa cause children to distrust authority in general, and is this a good or bad thing? I spell out my opinion in the previous post, but to quickly summarize – I think the overall effect is probably minor, in terms of harming trust in authority. But also, we should not assume that teaching children to question authority, and that there are no ultimate “Guardians of truth” is a bad thing. Perhaps it’s beneficial.

But as I discuss, there is a balance. We don’t want to create conspiracy theorists who distrust all institutions and experts on principle. But we also don’t want people who gullibly trust every perceived authority figure. A healthy doubt and skepticism toward any claims, toward any perceived authority, is a good thing, as long as it’s balanced with an appropriate respect for expertise and professionalism, and a proper humility about ones’ own abilities and knowledge.

Does Santa hit this sweet spot? It probably depends on the behavior of the parents. My approach was to basically play it cool. My wife and I neither encouraged nor discouraged belief in Santa. Our children believed because it was baked into society, and they absorbed the belief. But we always treated Santa as an idea, not a real person, and always with a wink and a nod. We also mixed in other playful things around the holiday, like one year giving gifts from The Doctor – because we were watching Dr. Who as a family then. I also never directly lied to my children, and when they asked questions I encouraged it. I did not pretend to have secret knowledge as a parent – Santa was as mysterious to me as he was to them, so let’s think about it together. They figured it all out on schedule without any issues.

We also emphasized what the holiday season (whatever your cultural or religious background) is generally about – connecting with family and loved ones, and showing other people that you care about them and think about them. So we also always emphasized that we were giving gifts to other people, and as soon as our children were old enough they participated in the gift giving as well (even if it was just helping pick out a gift for others). They knew that people were giving each other gifts at Christmas – it wasn’t all some jolly sprite.

In the end this may all be a metaphor for life itself. You can be a hard-core materialist, and still revel in the full human experience, without any belief in magic. Humans like to tell stories, we need connections with other people, we thrive when we have a sense of purpose and meaning. Even if meaning is ultimately subjective, who cares? We make our own meaning, which is both empowering and freeing. We don’t inherit purpose from society, from some ancient belief system that is handed down to us. Some things in the world are real, some are not, some are metaphors or just feelings. We ultimately have to work it all out for ourselves.