Jul 08 2019

Cancer Quackery on YouTube

Many outlets are covering the story of Mari Lopez, a YouTuber who claimed, along with her niece, Liz Johnson, that a raw vegan diet cured her breast cancer. Johnson recently updated the videos with a notice that Mari Lopez died of cancer in December 2017. She has refused, however, to take down the videos.

are covering the story of Mari Lopez, a YouTuber who claimed, along with her niece, Liz Johnson, that a raw vegan diet cured her breast cancer. Johnson recently updated the videos with a notice that Mari Lopez died of cancer in December 2017. She has refused, however, to take down the videos.

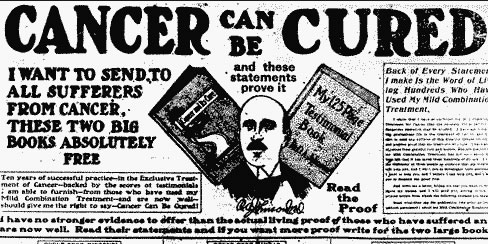

The story, unfortunately, is a common one. When people are diagnosed with cancer it is understandably a psychological shock. They face not only the grim possibility of their death, but also the prospect of surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy – none of which are pleasant. It is a life-altering event. It also makes people vulnerable – in that situation, who wouldn’t want an escape hatch, a way to get back to their normal life? That is what cancer quackery offers – forget surgery and chemotherapy, just engage in this mild intervention, like a diet change, and your cancer will be gone.

Those who get lured in by this siren song experience one of several possibilities. First, many may still undergo some initial treatment, such as surgery, to treat the cancer, but then refuse adjunctive therapy like chemotherapy or radiation. Some of those patients may, in fact, be cured by the surgery. Often the purpose of the chemotherapy is to reduce the risk of recurrence. Others may forgo any science-based treatment.

Following the initial diagnosis, with or without some intervention, there is what we call the honeymoon period. In this phase the cancer may be relatively asymptomatic. This is especially true if it was discovered because of some screening test, like an X-ray or blood test, and not because it had already become symptomatic. This period can last for months and even years, depending on the stage and type of cancer. This is the phase where those who pursued some form of cancer quackery convince themselves that they are cured. They will also tend to credit the alternative treatment with their cure, even if they received surgery or some other standard treatment.

For months or years they can then shout to the world that they cured themselves of their cancer with whatever cancer quackery they fell victim to. If they ultimately survive, they become an anecdote used to “prove” the efficacy of the treatment. If, however, they have a recurrence or even die of the disease, we generally just stop hearing from them. If there is any follow up it is brief, and often accompanied by the usual excuses – those which essentially amount to, they didn’t believe hard enough. Or, hey, we never said it was 100% effective. None of this stops the next victim from going through the same cycle, and luring in the next victim while they are in their own honeymoon phase.

Mari Lopez falls cleanly into this pattern. She was diagnosed with breast cancer. She decided to forgo standard treatment, event though breast cancer is highly curable, and instead opted to treat her cancer with a raw vegan diet. In an interview she perfectly reflected the attitude of the honeymoon phase:

“It’s my choice, I’ve been okay, I haven’t died, I haven’t gotten to the hospital. I am going to continue on this path of going natural,” Lopez said. “It’s [cancer] over, it is done with, I am healed. I feel it in my spirit and in my body.”

She believed this while the cancer was slowly spreading. Eventually it metastasized to the blood, bone, and liver. Liz reports that the cancer “returned” but there is no evidence it was ever gone. It just continued to advance. And then in December 2017 Mari sadly died, of a cancer that very likely could have been cured. Before her death she asked Liz to take down the videos, but she refused.

According to all reports, Liz exhibits all the signs of full denial. How does she explain the failure of the vegan diet?

“My aunt was inconsistent in her diet and spiritual life,” she wrote on YouTube. “[She] did not continue [a] juicing/raw vegan diet when she got diagnosed again, she chose to do radiation and chemo.”

She lost faith in the end. Liz also blames eating food cooked in a microwave. And of course, in desperation (also common) Mari relented late in the game and acquiesced to standard treatment, but it was too late. But that allows Liz to blame the science-based treatment on her aunt’s death. Of course, the simplest explanation is that the vegan diet did nothing for the cancer, which simply went through its natural history with a completely predictable outcome. No evidence, however, will shake the true-believer. I should note at this point that there is no evidence that any diet can treat cancer. Restrictive diets, if anything, are only likely to sap the patient of needed strength and nutrition as they fight the cancer and to recover from treatment.

There is another aspect to this story, which is incidental but is also very common – there was definitely a spiritual angle to Mari’s faith in the vegan diet. She reported that God lead her to the best fruits and vegetables to treat her cancer. She also believes that faith cured her of her homosexuality. Faith and spirituality are intimately intertwined with so-called alternative treatments, and this case is a good reflection of that.

There is nothing new in this case, it is sadly typical. But it has spawned a serious question in the age of social media. The Washington Post reports:

Google and Facebook have promised to crack down on health misinformation in recent months, as links between anti-vaccine conspiracy theories and measles outbreaks in the United States become major news.

They are relying on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which they say gives them the power to police their platforms, and shields them from liability for doing so. There are a few ways to combat quackery on YouTube and other platforms. The first is to simply ban such content. Of course, this will result in the usual cries of “free speech” – but free speech is not a license to practice medicine. It is reasonable to consider that if someone gives specific advice, such as – do not use chemotherapy or radiation, instead use my diet to treat your cancer – they are essentially practicing medicine.

Admittedly this is a gray zone. They can always claim they are giving general advice, not treating a specific person, and can further shield themselves with boilerplate disclaimers. In the age of social media, however, perhaps we need to recalibrate exactly where the line is. One important aspect of this is that often we are not talking about opinion. People might claim things in their videos that are demonstrably and objectively wrong, as far as we can tell based on current scientific evidence. That is the same standard we use to hold actual doctors to the standard of care. If the state can act against a doctor’s licence for telling their patients something that is wrong, why can non-experts get away with it? I am not saying put them in jail or even fine them, simply saying they should not necessarily have unlimited social media privileges.

You can limit people’s right to post videos if they use content that infringes on someone else’s copyright, and also if it constitutes slander. There are also decency standards against pornography on certain platforms, and also other content, such as snuff films, that can be considered exploitative or necessitate the committing of a crime. It is unreasonable to include a standard restricting content that poses a clear public health threat?

Short of banning, outlets can also tweak their search algorithms to favor authoritative sources over individual unreliable content. If you search for “cure for cancer” what comes up in the first 20 or so results? YouTube can say – feel free to post your nonsense, but we are under no obligation to serve it up to people who are innocently searching for information. YouTube, Facebook, and Google should not be viewed as passive platforms devoid of any responsibility. Their algorithms are active – they choose what content floats to the top. They are entirely open about the fact that quality of content is a main criterion, and so considering scientific accuracy is perfectly reasonable.

Platforms can also refuse to allow advertising to monetize content they deem to be harmful or exploitative.

I know this raises a bigger issue, because it puts a lot of power in the hands of a few corporations. That is a deeper problem we have to think about and address. Meanwhile, part of any solution should consider the effects on society of the way these megaplatforms handle information.