Sep 08 2022

Two New Nearby SuperEarths

As a SciFi fan, I have a lot of pet peeves (as most hard core fans probably do). While I love the freedom and imagination of speculative fiction, it’s easy to fall into common tropes that have emerged to facilitate story telling or simply due to lack of imagination. The problem is worse with science fiction in film and TV because of budgetary concerns (although CG is making this less of a restraint). For example, aliens tend to be far too human and generally have a monolithic culture.

As a SciFi fan, I have a lot of pet peeves (as most hard core fans probably do). While I love the freedom and imagination of speculative fiction, it’s easy to fall into common tropes that have emerged to facilitate story telling or simply due to lack of imagination. The problem is worse with science fiction in film and TV because of budgetary concerns (although CG is making this less of a restraint). For example, aliens tend to be far too human and generally have a monolithic culture.

Alien worlds also are too frequently Earth-like (mostly because the filming takes place on Earth). It’s one thing if your starship is visiting a world because it is habitable, but often our heroes come upon an apparently random planet that is unrealistic Earth-like. There are many exceptions to this in science fiction film and literature, but it still happens frequently, enough to be considered a trope. Think about all the ways in which the environment of even an Earth-sized planet in its habitable zone could vary. There’s always not only oxygen (even on apparently barren worlds) but enough oxygen. The gravity is always about 1G, the sun is always a nice yellow sun, and while the temperature may vary it’s always within survivable range.

The reality is that, by chance alone, something would be off. Now that we have the ability to actually discover exoplanets, that is exactly what we are finding. Astronomers estimate that there are likely between 300 million and 6 billion Earth-like planets in the milky way. That’s a big number, but there are 100-400 billion stars in the Milky Way, so that means on average about 1% of star systems contain an Earth-like planet. Also, what do we consider “Earth-like”? Generally that is any planet that is rocky and is in its star’s habitable zone, which means there can be sustainable liquid water on the surface. But that allows for a great deal of variability.

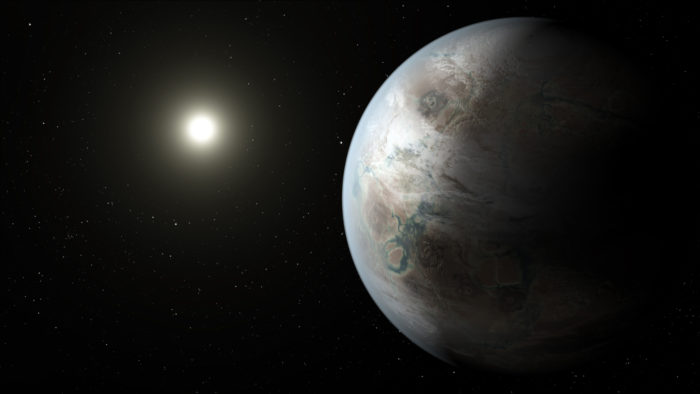

While our exoplanet data is still miniscule compared to what’s out there, we have confirmed over 5,000 exoplanets. That’s enough of a sampling to start to do some statistics. Of those 5,000+ planets, we have yet to find Earth’s twin. NASA considers Kepler-452b to be the closest candidate so far, although it is 60% bigger than Earth with 5 times the mass and 20% brighter. But it does orbit a star like our own at a similar distance with a 385 day year. We don’t yet know if it has an atmosphere. It’s surface gravity would be about twice that of Earth.

Here are the 10 most Earth-like exoplanets so far. Many are super-Earths, some orbit red Dwarfs, and some are on the edge of their habitable zone. None are likely to be comfortable for humans (even with supplemental oxygen). Even after 5,000 exoplanets, we haven’t found a single one that an away-team from the Enterprise could beam down to without protective gear and some uncomfortable gravity. One caveat is that the sampling is not exactly random. It favors larger planets and planets closer to their parent stars. But as new instruments come online our sampling is getting better.

Now we have two more “Earth-like” planets to add to the list, both super-Earths. Both orbit a nearby star (100 light years) that for some reason has three names – LP 890-9, TOI-4306 or SPECULOOS-2. In the exoplanet naming convention, the parent star is “a” and the discovered planets start with “b”, so now we have SPECULOOS-2b and c. The star is a red dwarf, a very cool star, and therefore in order for these planets to be in the habitable zone they have to be very close, with orbital periods of 2.7 and 8.5 days. They are both a little larger than Earth, 30% and 40% respectively.

Being so close to their parent star almost certainly means that they are tidally locked, meaning that one face of the planet always points toward the star. This is not necessarily a deal-killer for habitability. Liquid water and an Earth-like atmosphere would actually be highly efficient at distributing heat from the hot side to the cool side. This could result in a vast temperate zone around the planet. These planets could therefore harbor life.

The real challenge for life on planets that orbit red dwarfs is that the early life of these stars is very chaotic. They produce high energy CMEs that would likely sterilize close-up planets and strip their atmospheres. But it is possible that such planets may reconstitute an atmosphere after their host star settles down. Or they could migrate in from the outer stellar system after the dangerous period is over. But still, it’s likely that most such planets may have had their atmospheres stripped.

It’s still too early to say how many planets in our galaxy are likely to have life. We also have to broader our conception of what worlds may have life – do we include large moons of gas giants, for example? What about rogue planets? For now we can only continue to gather data.