Aug 21 2015

Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease

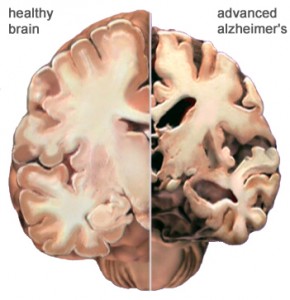

A new meta-analysis of 323 studies looks at 93 possible factors associated with the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting the entire brain that causes a slowly progressive dementia over years.

A new meta-analysis of 323 studies looks at 93 possible factors associated with the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting the entire brain that causes a slowly progressive dementia over years.

Dementia is a generic term for a chronic disorder of memory and cognition. AD is a specific disease that causes dementia. It is the most common cause of dementia, responsible for about half of all cases. There are 5.2 million people with AD in the US, most over the age of 65. About one-third of people 85 years or older have AD.

AD, therefore, is a significant cause of a common condition that causes extreme disability and death in the older population. There is currently no cure for AD. Available treatments are considered symptomatic – they improve memory and function modestly but do not alter the course of the disease. Preventing AD, therefore, is very important.

The current meta-analysis looked at cohort studies and case-control studies. These are two different types of observational studies, meaning that they are observing what happens or has happened to people but does not randomize people to different groups. It is difficult to draw conclusion about cause and effect from observational studies because of possible confounding factors. The advantage, however, is that they can observe large populations. In the current analysis the researchers looked at 93 factors with >5,000 subjects in the pooled studies.

This is what they found (summary from the abstract):

Among factors with relatively strong evidence (pooled population >5000) in our meta-analysis, we found grade I evidence for 4 medical exposures (oestrogen, statin, antihypertensive medications and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs therapy) as well as 4 dietary exposures (folate, vitamin E/C and coffee) as protective factors of AD. We found grade I evidence showing that one biochemical exposure (hyperhomocysteine) and one psychological condition (depression) significantly increase risk of developing AD. We also found grade I evidence indicative of complex roles of pre-existing disease (frailty, carotid atherosclerosis, hypertension, low diastolic blood pressure, type 2 diabetes mellitus (Asian population) increasing risk whereas history of arthritis, heart disease, metabolic syndrome and cancer decreasing risk) and lifestyle (low education, high body mass index (BMI) in mid-life and low BMI increasing the risk whereas cognitive activity, current smoking (Western population), light-to-moderate drinking, stress, high BMI in late-life decreasing the risk) in influencing AD risk. We identified no evidence suggestive of significant association with occupational exposures.

The authors suggest that if the nine largest factors were optimized in the population the incidence of AD could be reduced by 2/3.

Again – this is observational data, so these conclusions have to be taken with a huge grain of salt. Some of these factors are also likely related. For example, folate reduces homocysteine, so perhaps the protective effect of folate is essentially the same factor as the risk of increased homocysteine.

The second most common cause of dementia is vascular, and there is a large overlap of AD and vascular dementia. Therefore it is not surprising to see some vascular risk factors on the list – carotid stenosis, hypertension, and diabetes. Vascular treatments also lower risk of AD – anti-hypertensives, statin drugs, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (aspirin-like drugs).

Many of the factors are nutritional. There is evidence that overall poor nutrition, and low levels of specific micronutrients, are linked to AD. I say “linked” because we don’t know for sure the cause and effect. Patient with AD do not eat as well, or the disease itself may lower micronutrient levels due to increased demand. Either way optimizing nutrient levels is potentially beneficial.

Some of the identified factors are complex, and given observational data only I don’t think lead to any strong recommendations. For example, I would not recommend drinking, taking up smoking, or drinking coffee with the idea it will reduce your AD risk. These are complex factors likely obscured by confounding factors, and also with other risks not associated with AD.

What should the average person do with this information? First, let’s look at the low-hanging fruit or the win-wins. If you have high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, or metabolic syndrome then follow up closely with your doctor and make sure these conditions are being adequately treated. You should be doing that anyway, and here is possibly another benefit.

Stay mentally and physically active. Engage specifically in novel mental activities.

Maintain a healthy weight – which means not being obese when middle-aged and not being underweight when older.

What about vitamins and supplements? Most physicians will routinely test folate, B12, and homocysteine levels, especially in older patients, and supplement accordingly. That is better, in my opinion, than blind supplementation. I see many patients with high, and even toxic, levels of certain vitamins. At the very least you can avoid paying for and taking vitamins you don’t need.

Taking daily aspirin has risks and benefits, so again it is best to consult your primary care doctor. Reducing risk of AD is possibly another benefit to throw into the calculation and an additional motivation to be compliant.

Conclusion

This latest meta-analysis is helpful in reviewing the last 50 years of research into risk factors for AD and shows that there is the potential to reduce the incidence of this disease. In the end, however, most of the advice that flows from this data are thing we already knew.

For the average person the resulting advice is simple.

– See your primary care doctor and treat chronic health conditions and risk factors.

– Have an overall healthful diet and maintain a healthy weight.

– Stay mentally and physically active.

– Talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of daily aspirin and also doing blood work for nutritional factors, like folate and B12.