Apr

05

2021

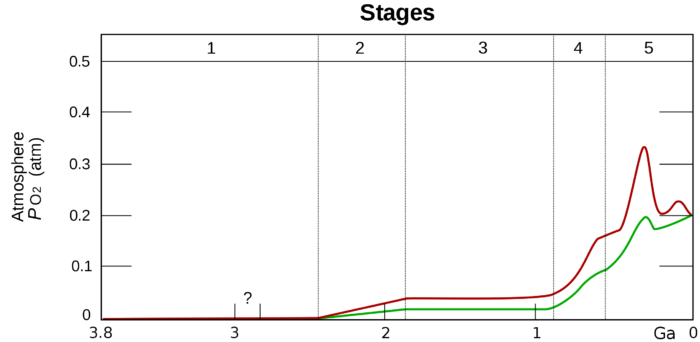

The deep history of the Earth is fascinating, and while we have learned much about the distant past there are still many puzzle pieces missing. A new study tweaks our understanding of one of the biggest events in Earth’s history – the Great Oxygenation Event, and also helps better align the other big events in the past.

The deep history of the Earth is fascinating, and while we have learned much about the distant past there are still many puzzle pieces missing. A new study tweaks our understanding of one of the biggest events in Earth’s history – the Great Oxygenation Event, and also helps better align the other big events in the past.

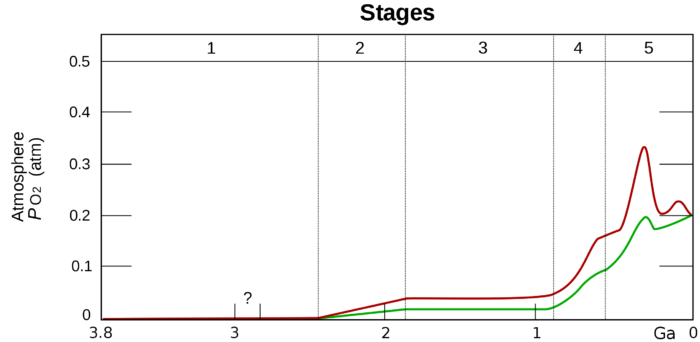

The Earth as we know it formed about 4.5 billion years ago. Earth is actually Earth 2.0 – the proto-Earth was hit by a Mars-sized object, forming both the current Earth and the Moon. The Earth was fairly molten at this time, still hot from all the impacts, but over the next millions of years the surface cooled, stable pools of liquid water formed on the surface, and it had a stable atmosphere of mostly nitrogen. In this environment life evolved. We are not exactly sure when, but probably by 3.5 billion years ago. There is good evidence for cyanobacteria by 2.9 billion years ago. These critters are important, because they make food from sunlight and produce oxygen as a waste byproduct. For millions of years oceans full of cyanobacteria cranked out oxygen, which built up in the atmosphere.

This is where the new study comes in – it explores exactly when oxygen built up to high levels. The current atmosphere is about 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, 0.04% carbon dioxide, and trace amounts of methane and other gases. Prior to about 2.45 billion years ago there was essentially zero oxygen in the atmosphere. Between 2.45 and 1.85 billion years ago oxygen built up slowly in the atmosphere, up to 3-5%, but was also mostly absorbed by the oceans and seabed rock. This is the Great Oxygenation Event, still little oxygen by today’s standard, but enough to usher in a major change in the chemistry of earth. From 1.85 to 0.85 billion years ago oxygen had saturated the ocean and so now spread to the land where it was further absorbed into rocks and minerals. During this time atmospheric O2 levels were pretty stable at 3-5%. But then, starting 0.85 billion years ago the surface of the Earth had absorbed all the oxygen it could (the oxygen sinks were full) and so O2 started building up in the atmosphere significantly, peaking about 400 million years ago at over 30% and then settling down to the current 21%. Oxygen levels are now slowly and steadily decreasing.

Continue Reading »

Mar

04

2021

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can pass the marshmallow test.

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can pass the marshmallow test.

The “marshmallow test” is a psychological experiment of the ability to delay gratification. The basic study involves putting a treat (like a marshmallow, but it can be anything) in front of a young child and telling them they can have it now, or they can wait until the adult returns at which time they will be given two treats. The question is – how long can children hold out in order to double their treats? The interesting part of this research paradigm are all the associated factors. Older children can hold out longer than younger children. The greater the reward, the more children can wait for it. Children who find ways to distract themselves can hold out longer.

For decades the test and all its variations was interpreted as a measure of executive function, and correlated with all sorts of things like later academic and economic success. However, more recent studies have found (unsurprisingly) that there can be confounding factors not previously recognized. For example, children from insecure environments have not reason to trust that adults will return with more treats and therefore take what is in front of them. This could be seen as an adaptive response to their environment.

Continue Reading »

Mar

02

2021

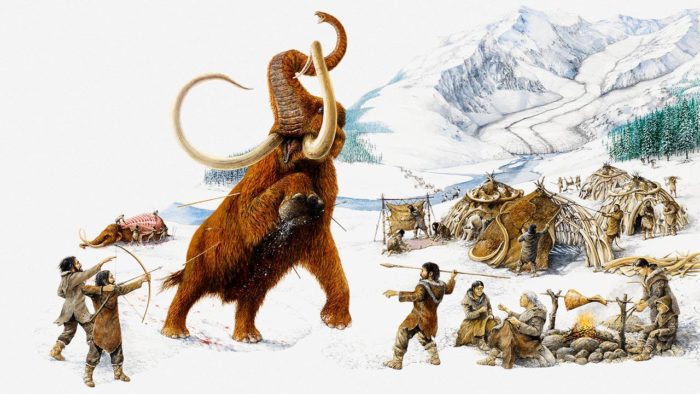

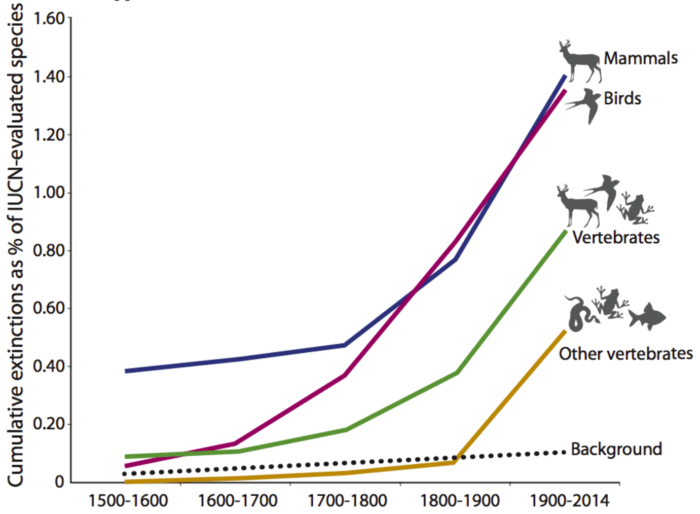

One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why?

One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why?

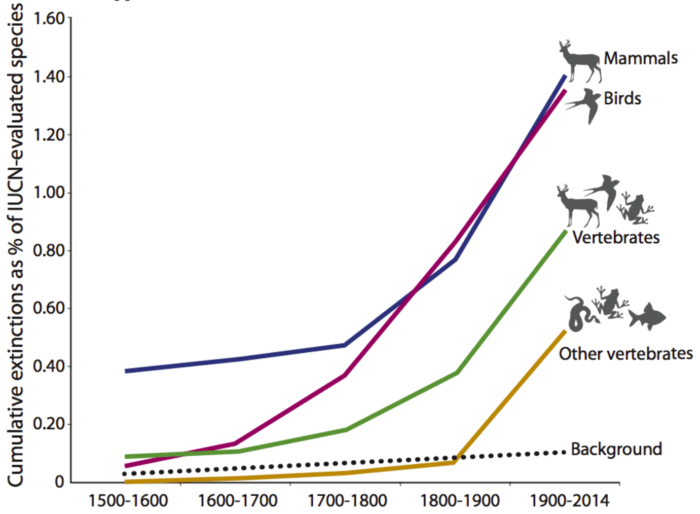

I recently wrote about the North American megafauna, and the debate between whether their extinction about 12 thousands years ago was caused primarily by humans (the overkill hypothesis) or climate change. But this debate exists for the entire planet – every continent except Antarctica. This continues to be a debate because large-scale cause and effect is difficult to prove in evolutionary history. We can test various hypotheses by predicting correlations and patterns in the fossil record and then looking for them. Sometimes we can extrapolate from current observable trends, or even changes in the laboratory. But the steady reduction in the average size of mammals requires looking for large correlations – what factor does this trend most have in common around the world? Many scientists think the clear answer is – humans.

Starting with Homo erectus, wherever humans go around the world they are followed by a wave of megafauna extinction. Could this just be a general trend unrelated to humans? Perhaps the world’s climate has been changing in such a way over the last two million years that explains a selective advantage to small size. Climate cannot be ruled out as a factor, but the evidence increasingly supports the notion that human hunting played a major factor.

I am always suspicious of nice clean stories in evolution, so I will add a huge caveat that any hypothesis about A causing B is likely to be a massive oversimplification. But some factors can have dominant effects. Around 2 million years ago we start to see the first evidence of Homo erectus using fire. At this same time erectus clearly dramatically ramped up their hunting, and also this was the first time a human species spread throughout the world. Cooking meat would have been a huge energy and nutritional advantage, and hunting requires a lot of land, and hence the need to spread out. This shift in our human ancestors correlates nicely with dramatic reductions in the average size of mammals, wherever humans went.

Continue Reading »

Feb

16

2021

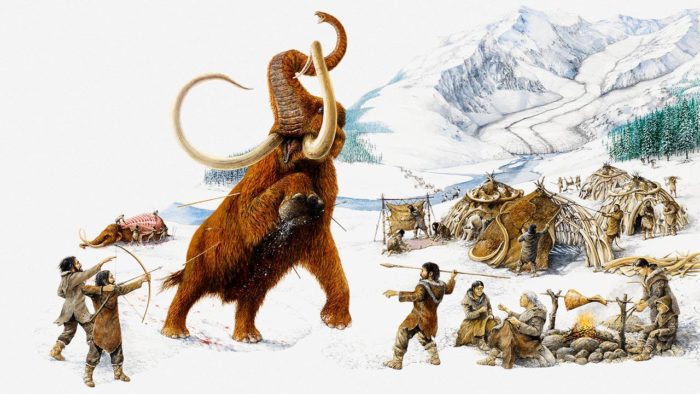

Before around 13,000 years ago large mammals walked North America – the Mammoth, most famously, but also giant beavers, giant tree sloths, glyptodonts, and the American cheetah among them. By around 11,000 years ago they were all gone (38 genera, mostly mammals). Extinction is a natural part of the cycle of ecosystems, and no species lasts forever. But when paleontologists identify a pulse of extinctions, above the background rate, they call that an extinction event, and this definitely qualifies. Extinction events call out for answers – what was the cause?

Before around 13,000 years ago large mammals walked North America – the Mammoth, most famously, but also giant beavers, giant tree sloths, glyptodonts, and the American cheetah among them. By around 11,000 years ago they were all gone (38 genera, mostly mammals). Extinction is a natural part of the cycle of ecosystems, and no species lasts forever. But when paleontologists identify a pulse of extinctions, above the background rate, they call that an extinction event, and this definitely qualifies. Extinction events call out for answers – what was the cause?

In the case of the North American megafauna extinction, there are two main hypotheses. The first is the overkill hypothesis – that the extinction coincides with the arrival of paleoindians on the continent, and that is not likely a coincidence. Generally speaking the arrival of humans into any ecosystem correlates with a pulse of extinctions. Perhaps the humans taking up residence in North America were big-game hunters, and the megafauna could not adapt quickly enough to this clever predator.

The second major hypothesis is that climatic change was the major cause. The last major glacial period lasted from 125,000 to 14,900 years ago, and then started the current interglacial period (the holocene) that we are in. However, this warming was interrupted in North American by the Younger Dryas, a cold snap that lasted from 12,900 to 10,600 years ago. The cause of this cold spell is also a controversy, with the two main hypotheses being a local comet impact vs the effects of major glacial melt on ocean currents. Either way, by the time the cold snap was over, the megafauna was gone.

Continue Reading »

Oct

30

2020

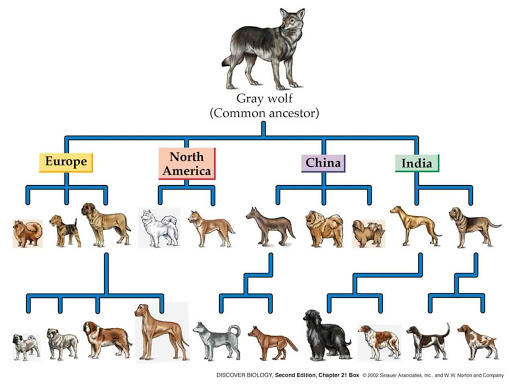

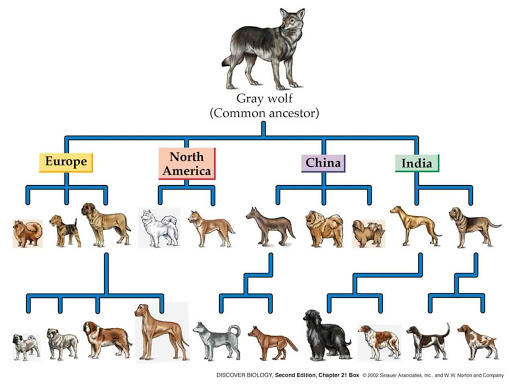

The evolution of dogs from wolves is a long and complex one. A recent study adds some further information to this tale – as long as 11,000 years ago there were already at least five different distinct breeds of dog. These different breeds partly tracked along with human populations, but not completely. But let’s back up a bit and see where this new information fits into the story.

The evolution of dogs from wolves is a long and complex one. A recent study adds some further information to this tale – as long as 11,000 years ago there were already at least five different distinct breeds of dog. These different breeds partly tracked along with human populations, but not completely. But let’s back up a bit and see where this new information fits into the story.

Experts actually don’t agree on exactly when and where dogs first appeared, or even if it was one event or multiple independent origins. What is clear is that dogs are essentially domesticated wolves. Their likely origin was in Europe sometime between 19 and 32 thousand years ago. This makes dogs the first domesticated animal. I have often considered (being a life-long dog owner myself) how useful dogs would have been to ancient people. They are excellent guardians, sending up an alarm when anything strays too close to camp. My dog will let me know when racoons are poaching the bird feeder at 3am. They are territorial and will keep critters small and large out of the area. And in an emergency they will even fight for their masters. More developed and trained dogs can also do all sorts of jobs, from herding to hunting.

The extreme usefulness, not to mention companionship, of dogs to humans lead to the early hypothesis that humans domesticated wolves, probably by first raising wolf pups. Tamed wolves are more aggressive than dogs, but they can bond with humans and function in the human world. We know from the silver fox experiments that some mammal species can be significantly domesticated in just a few generations. So it would not take long for these tamed wolves to become more docile, loyal, and obedient. But experts now suspect this is not what actually happened.

The history of human and wolf interaction is mainly one of competition and eradications. Humans have always treated large predators as a threat. Wolves specifically have mostly been eradicated where humans flourish, often deliberately. This still does not preclude the exception of tamed wolves, but it did give rise to an alternate hypothesis – perhaps wolves domesticated humans rather than the other way around, meaning that it was the wolves who changed the nature of our relationship first. In this scenario wolf populations living near humans may have learned to poach at the edges of settlements, perhaps eating the bones or other refuse that humans discarded. The more cute and friendly wolves would have had more success at this strategy, while the more aggressive wolves would have been killed or driven off. This could have led to a subpopulation of friendly wolves mostly living off of human refuse. Selective pressures could have then quickly domesticated these proto-dog wolves, who were only later taken as companions by humans. Human selection would then have taken them the rest of the way to modern dogs.

Continue Reading »

Sep

28

2020

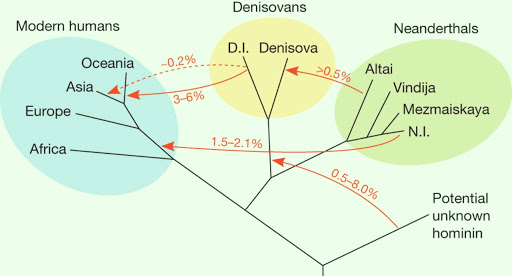

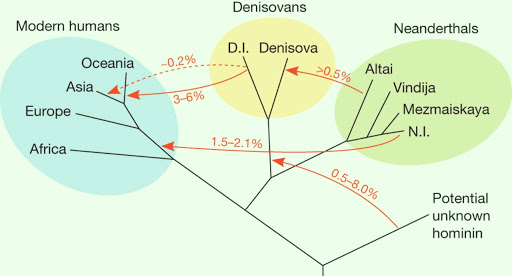

Recent human ancestry remains a complex puzzle, although we are steadily filling in the pieces. For the first time scientists have looked at the Y chromosomes of modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans, giving us yet one more piece of the puzzle. But first, here’s some background.

Recent human ancestry remains a complex puzzle, although we are steadily filling in the pieces. For the first time scientists have looked at the Y chromosomes of modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans, giving us yet one more piece of the puzzle. But first, here’s some background.

The common ancestor of humans (by which I mean modern humans), Neanderthals, and Denisovans lived between 500,000-800,000 years ago. This common ancestor species almost definitely lived in Africa, but we are not sure exactly which species it was. Homo heidelbergensis is a candidate, but it’s not clear if the timeline matches up well enough. In any case, this split probably occurred when the ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans migrated from Africa to Europe. They then split from each other, with the Neanderthals remaining in Europe and the Denisovans going to Asia. This split happened around 600,000 years ago, but could be more recent.

Why is there so much confusion about the exact time of the split? There are two main reasons. The first is that these splits were not single events. Populations of early humans became relatively separated from each other, enough so that genetic differences could start piling up. But they also continued to interbreed, sharing genes throughout their history. There is a specimen that is likely the child of a Neanderthal and a Denisovan from just 50,000 years ago. Humans and Neanderthals interbred right up until the end. All non-African humans living today have 2-3% Neanderthal DNA.

The other reason the divide is difficult to pin down is because there are numerous methods for estimating when it occurred, and they give slightly different answers. We can look at teeth, and other fossil bones, and genomic DNA, mitochondrial DNA, or specifically X and Y chromosomes. We can also look at their culture via their tools. We can see when certain tools start appearing in different locations. Culture, by the way, can also be shared among populations, so that picture may be confused as well.

Continue Reading »

Mar

12

2020

We like extremes, partly because they help define the borders of reality. It helps our mental model of the world when the know the biggest, smallest, hottest, lightest, or fastest of something. It’s also just fascinating to see how extreme some things can get. For this reason there has been a fascination with which dinosaur is the biggest – how big did these animals get. The record is currently held by Argentinasaurus, a long-necked sauropod, weighing between 77 and 110 tons. Meanwhile, the record for the smallest known dinosaur is microraptor, a bird-like dinosaur only 40 cm long. Well, that is until the latest discovery.

We like extremes, partly because they help define the borders of reality. It helps our mental model of the world when the know the biggest, smallest, hottest, lightest, or fastest of something. It’s also just fascinating to see how extreme some things can get. For this reason there has been a fascination with which dinosaur is the biggest – how big did these animals get. The record is currently held by Argentinasaurus, a long-necked sauropod, weighing between 77 and 110 tons. Meanwhile, the record for the smallest known dinosaur is microraptor, a bird-like dinosaur only 40 cm long. Well, that is until the latest discovery.

Scientists report the discovery of the head of a bird-like dinosaur trapped in amber. The species has been named Oculudentavis khaungraae and is about the size of a bee hummingbird, the smallest living bird. The specimen is trapped in amber from Myanmar, and is dated at 99 million years old. The amber preserved some soft tissue, including its tongue. The specimen is interesting on multiple levels.

First, it reflects the extreme of vertibrate miniaturization. It’s difficult to cram all the sensory organs into a tiny skull, and species that evolve to become so small have to find solutions. In this case the eye socket anatomy appears different than hummingbirds and other tiny birds. Rather than a rim of bone, the socket is more spoon-shaped. The anatomy also suggests a small opening for light, which further implies the species was diurnal.

The mouth sports a surprising number of teeth, making the creature look like a predator. At that size is likely fed on insects. So we have a bird-like dinosaur the size of a tiny hummingbird that hunted insects during the day. The anatomy, such as fusion of the skull, also suggests this was an adult, so not just a juvenile specimen to explain its small size.

Continue Reading »

Mar

02

2020

Another paper has been published in the simmering controversy over whether or not proteins, and even DNA, can survive millions of years in well-preserved dinosaur (non-avian dinosaurs, that is) fossils. The paper looks at cartilage from a duck-billed dinosaur, a young Hypacrosaurus stebingeri. The authors claim:

Another paper has been published in the simmering controversy over whether or not proteins, and even DNA, can survive millions of years in well-preserved dinosaur (non-avian dinosaurs, that is) fossils. The paper looks at cartilage from a duck-billed dinosaur, a young Hypacrosaurus stebingeri. The authors claim:

“…microstructures morphologically consistent with nuclei and chromosomes in cells within calcified cartilage. We hypothesized that this exceptional cellular preservation extended to the molecular level and had molecular features in common with extant avian cartilage. Histochemical and immunological evidence supports in situ preservation of extracellular matrix components found in extant cartilage, including glycosaminoglycans and collagen type II. Furthermore, isolated Hypacrosaurus chondrocytes react positively with two DNA intercalating stains.”

Let me say right away that these claims are controversial, but what would they mean if true? If we could examine the structure of proteins and DNA from >65 million years ago, in well-preserved dinosaur fossils, then the world of molecular biology would extend back to that era. Molecular examination has had a significant impact on paleontology – but it has limits. So far the oldest DNA sequenced from a fossil is from a 700,000 year old horse frozen in ice. The oldest protein so far confirmed is from a rhino 1.7 million years old. This means that if the current claims are true, DNA can survive in fossils 100 times longer than the current record would indicate.

This is also not the only source of information from which to estimate the lifespan of DNA. Researchers have examined DNA from Moa specimens in New Zealand, over a span of about 8,000 years. This allowed them to estimate the half-life of DNA, the time over which about half the bonds would be broken. Their estimate – 521 years. This means that all the chemical bonds in a DNA molecule would be gone after 6.8 million years, but having any fragments along enough to sequence would be gone after about one million years. This aligns nicely with the evidence from actual fossils. So claiming DNA from >65 million years would be extraordinary, to say the least. This is why most scientists remain skeptical of these claims.

Continue Reading »

Nov

07

2019

The evolution of human bipedalism is one of the great events in the history of life that we still need to flesh out. We tend to focus on big transitions because of their implications for the story of life – the evolution of flight, moving out onto land, and the development of intelligence. There is still much we don’t know about the exact path taken in the development of human bipedalism, because we lack good windows into that time and place of our past.

The evolution of human bipedalism is one of the great events in the history of life that we still need to flesh out. We tend to focus on big transitions because of their implications for the story of life – the evolution of flight, moving out onto land, and the development of intelligence. There is still much we don’t know about the exact path taken in the development of human bipedalism, because we lack good windows into that time and place of our past.

Scientists have now described a new hominid species, which I’ll get to below, but first some background. The first evidence we have of hominid bipedalism is in Sahelanthropus tchadensis, which lived between 6 and 7 million years ago. For context, the last common ancestor with chimpanzees was between 8 and 6 million years ago, so this is pretty close to the transition. We only have skull specimens, but we can tell the species was bipedal because the foramen magnum, the opening for the spinal cord at the base of the skull, opens below like in humans, rather than toward the back like in all other apes.

About 6 million years ago we have Orrorin tugenensis, from which we have a thigh bone which suggests bipedalism. But the earliest human ancestor with extensive evidence of bipedalism is Ardipithecus ramidus, dating to 4.4 million years ago. We have several specimens, the best of which, “Ardi”, contains foot and limb bones. Ardi has clear adaptations to bipedalism, but also for tree climbing.

Keep in mind, we did not evolve from chimpanzees – chimps and humans share a common ancestor. Chimps have diverged from that common ancestor as much as humans have. We don’t have any specimens that are candidates for that common ancestor, so we don’t really know what it was like. Chimps can walk on two legs part of the time, but they are not adapted to it. Chimps (and gorillas) knuckle walk – the walk on four limbs with their forelimbs resting on their knuckles.

Continue Reading »

Oct

31

2019

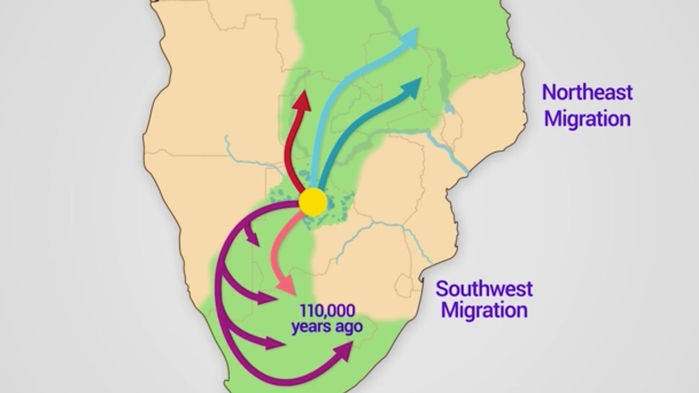

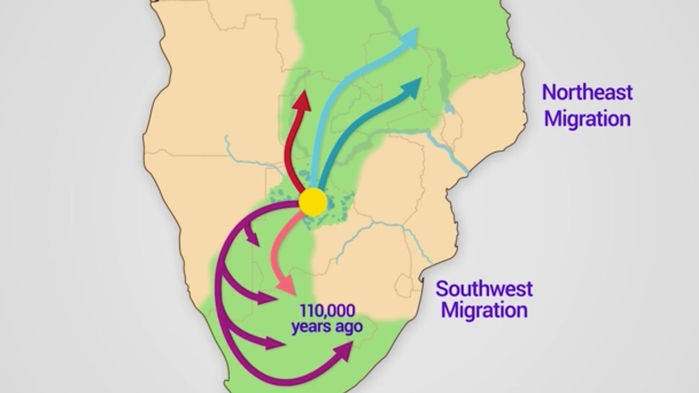

When and where did fully modern humans first emerge? That is an interesting question that paleontologists have been chasing for decades. Now a new genetic study claims to have pinpointed that origin to northern Botswana 200,000 years ago. The claim is already getting some pushback from other experts, but the new data does add to our understanding of human origins.

When and where did fully modern humans first emerge? That is an interesting question that paleontologists have been chasing for decades. Now a new genetic study claims to have pinpointed that origin to northern Botswana 200,000 years ago. The claim is already getting some pushback from other experts, but the new data does add to our understanding of human origins.

The study looks at mitochrondrial DNA, a technique that has been used before. This is DNA outside the nucleus, in each mitochondria of the cell (the power factories). They are almost exclusively passed down through the maternal line, because the egg provides all the mitochondria to the embryo, while sperm generally contribute none (although one may sneak through from time to time). You can therefore use mDNA to trace maternal lines.

When this type of analysis was first done researchers found that all humans have a common female ancestor going back to about 200,000 years in Africa. This result was widely misinterpreted in the press, not helped by the fact that this alleged ancestor was deemed the “mitochondrial Eve.” If you go back far enough, everyone is related to everyone. Therefore we all have many common ancestors. What the analysis shows really is a couple of things. First, that only one mitochondrial line from this time survived to the modern day. That doesn’t mean we only have one common female ancestor. But every time a woman has only sons, her mitochondrial line dies out. This finding does suggest, however, that the human population when through a relative bottleneck at this time. Our ancestors were not spread around Africa or the world, because then each region would have its own mitochondrial lineage.

Continue Reading »

The deep history of the Earth is fascinating, and while we have learned much about the distant past there are still many puzzle pieces missing. A new study tweaks our understanding of one of the biggest events in Earth’s history – the Great Oxygenation Event, and also helps better align the other big events in the past.

The deep history of the Earth is fascinating, and while we have learned much about the distant past there are still many puzzle pieces missing. A new study tweaks our understanding of one of the biggest events in Earth’s history – the Great Oxygenation Event, and also helps better align the other big events in the past.

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can  One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why?

One cartoon-cliché of “prehistoric” time is that everything was bigger. We grow up absorbing a picture of the vague deep past as including dinosaurs, cavemen, and big versions of everything. While this is an oversimplification, and tends to mash vastly different periods into one (the past), the notion that mammals, at least, tended to be bigger in the past is accurate. When mammals replaced dinosaurs as the dominant megafauna on land, they became really big (although not as big as the biggest dinosaurs they replaced). But then over the last 2 million years average mammals sizes have been steadily decreasing. The big question is – why? Before around 13,000 years ago

Before around 13,000 years ago  The evolution of dogs from wolves is a long and complex one.

The evolution of dogs from wolves is a long and complex one.  Recent human ancestry remains a complex puzzle, although we are steadily filling in the pieces. For the first time

Recent human ancestry remains a complex puzzle, although we are steadily filling in the pieces. For the first time  We like extremes, partly because they help define the borders of reality. It helps our mental model of the world when the know the biggest, smallest, hottest, lightest, or fastest of something. It’s also just fascinating to see how extreme some things can get. For this reason there has been a fascination with which dinosaur is the biggest – how big did these animals get.

We like extremes, partly because they help define the borders of reality. It helps our mental model of the world when the know the biggest, smallest, hottest, lightest, or fastest of something. It’s also just fascinating to see how extreme some things can get. For this reason there has been a fascination with which dinosaur is the biggest – how big did these animals get.  Another paper has been published

Another paper has been published The evolution of human bipedalism is one of the great events in the history of life that we still need to flesh out. We tend to focus on big transitions because of their implications for the story of life – the evolution of flight, moving out onto land, and the development of intelligence. There is still much we don’t know about the exact path taken in the development of human bipedalism, because we lack good windows into that time and place of our past.

The evolution of human bipedalism is one of the great events in the history of life that we still need to flesh out. We tend to focus on big transitions because of their implications for the story of life – the evolution of flight, moving out onto land, and the development of intelligence. There is still much we don’t know about the exact path taken in the development of human bipedalism, because we lack good windows into that time and place of our past. When and where did fully modern humans first emerge? That is an interesting question that paleontologists have been chasing for decades.

When and where did fully modern humans first emerge? That is an interesting question that paleontologists have been chasing for decades.