Mar 08 2018

Carbon Nanotube Supercapacitors

It has been simultaneously exciting and frustrating to follow energy technology news over the last couple of decades. There seems to be endless news stories about a “breakthrough” in technology for batteries, photovoltaics, supercapacitors, hydrogen fuel, and other ways to harvest and store energy. The breakthroughs, however, never seem to manifest.

It has been simultaneously exciting and frustrating to follow energy technology news over the last couple of decades. There seems to be endless news stories about a “breakthrough” in technology for batteries, photovoltaics, supercapacitors, hydrogen fuel, and other ways to harvest and store energy. The breakthroughs, however, never seem to manifest.

Reporting rarely puts the potential advance into proper context, or they gloss over the critical details. Even as a non-expert enthusiast who has been following these stories for a long time, I am occasionally tripped up by the misreporting of technical details.

A recent story about a supercapacitor “breakthrough” fits the common pattern, although it is better than many reports. The report begins:

Imagine being able to charge your electric car in minutes rather than hours, or your smartphone in seconds.

That’s the enticing prospect being touted by researchers who reckon they’ve discovered a new material that could boost the performance of a carbon-based supercapacitor – sometimes called an ultracapacitor – a type of energy storage device that can be charged very quickly and offload its power very quickly, too.

Except when you read through the story it becomes clear that the technology is nowhere near being able to charge your car in minutes, and probably never will be.

Here’s the pattern – incremental advances are presented as major breakthroughs. Or, more commonly, a significant advance in one aspect of the technology is touted, with brief mention (if at all) of the deal-killer downsides buried deep in the article. It is also almost ubiquitous that prototype advances made in the lab are showcased, with the caveat at the end (almost as an afterthought) – “If this technology scales up.” This means, the technology may not actually work or be able to be mass produced.

The problem, for journalists, is that the reality is not optimized for headlines and news articles. You never see a headline that says, “Another incremental advance will improve battery technology by 1% again this year.” But that is the reality.

It’s a good reality – battery, solar, and supercapacitor technology have been improving incrementally and steadily over the last few decades. While there is no sudden change or disruptive advance, the cumulative effect of these steady incremental advances has been great. We have slowly crept over the line where solar panels are cost effective, and electric cars have suitable ranges for everyday use.

These incremental advances are the result, often, of the “amazing breakthroughs” that we read about, it’s just that their ultimate effect is not the transformative changes promised. They just moved the ball forward a little bit, keeping the incremental advances coming.

Let’s get back to the recent supercapacitor article. Despite the promise in the headline and opening paragraph, this technology will not be used anytime soon to replace batteries, and may never be. A capacitor stores energy in a static electric field. The most basic capacitor is created by two conductive plate held closely together but separated by a small space. The electric fields (positive on one plate and negative on the other) want to pull the plates together, but they are physically held apart. This way the fields to not discharge and neutralize each other, and their energy can be stored.

Capacitors have several key advantages as an energy storage device for vehicles or other electrical devices. They can charge up very quickly, they can discharge large amounts of electricity quickly, and they can have many charge-discharge cycles. All of these features are far better than for batteries.

But capacitors have critical disadvantages also. They can only hold a relatively small amount of electricity, and they can only hold it for a short period of time. This means they are great for certain applications, but terrible for others.

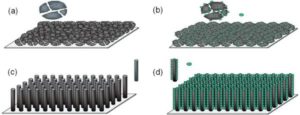

The new research shows that you can make supercapacitors out of carbon nanotubes (not a new idea, and long believed to be an application for graphene). Carbon is light and strong, and graphene conducts well. The article claims the new capacitors (at least the prototype) can store five times as much energy as existing capacitors. That’s great – but nowhere near what would be necessary to use a supercapacitor as a battery. This, again, will likely lead to an incremental advance, and put us on track for many more years of incremental advances.

The article does acknowledge (again, if you read through to the end) that capacitors such as this will likely not replace regular batteries. Instead, they will complement batteries. For example, in an electric vehicle regenerative braking can be used to capture energy that would otherwise be lost to braking. Capacitors are perfect for this, because they can capture that energy quickly, can do it many times without losing function, and can then give back that energy quickly – perfect for stopping and going in city traffic.

Using capacitors to do the heavy lifting for regenerative braking and accelerating can take a lot of wear and tear off the battery, extending the battery life.

This seems to be where things are headed, and this technology will extend the range and life of electric cars. The carbon based capacitors are also lighter, which is always good in a vehicle. It also does not use any rare or toxic material, which is a nice feature.

So I do expect to see carbon-based supercapacitors in electric vehicles, resulting in a nice improvement in overall performance. We won’t be charging up our cars in minutes because they are entirely powered by supercapacitors, however, yet that was the headline and opening paragraph. That is, essentially, the take-away of the article, and it is entirely misleading.

The real story fits a different narrative, slow steady improvement. I have learned to just focus on the steady incremental advances, and stop getting distracted by the promised breakthroughs. I doubt we will ever be rid of the click-bait “breakthrough” narrative, however.