Mar

04

2024

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

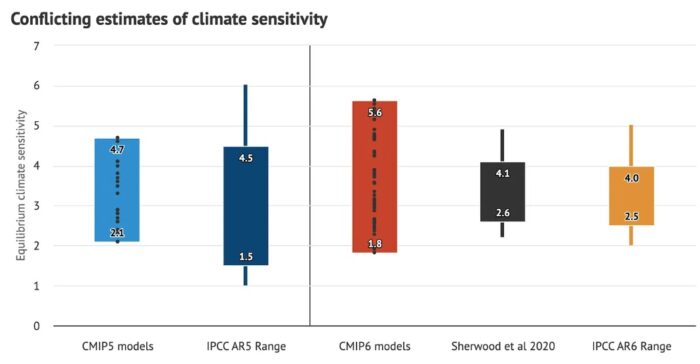

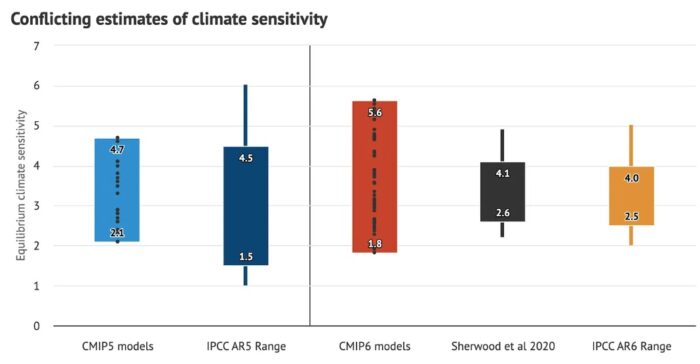

First let me review the relevant background. ECS is a measure of how much climate warming will occur as CO2 concentration in the atmosphere increases, specifically the temperature rise in degrees Celsius with a doubling of CO2 (from pre-industrial levels). This number of of keen significance to the climate change problem, as it essentially tells us how much and how fast the climate will warm as we continue to pump CO2 into the atmosphere. There are other variables as well, such as other greenhouse gases and multiple feedback mechanisms, making climate models very complex, but the ECS is certainly a very important variable in these models.

There are multiple lines of evidence for deriving ECS, such as modeling the climate with all variables and seeing what the ECS would have to be in order for the model to match reality – the actual warming we have been experiencing. Therefore our estimate of ECS depends heavily on how good our climate models are. Climate scientists use a statistical method to determine the likely range of climate sensitivity. They take all the studies estimating ECS, creating a range of results, and then determine the 90% confidence range – it is 90% likely, given all the results, that ECS is between 2-5 C.

Continue Reading »

Mar

21

2023

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

As is often the case, an optimal approach likely combines both strategies, trying to leverage the advantages of each. Therefore we often have disease headers with subtypes below to capture more detail. But even there the debate does not end – how far do we go splitting out subtypes of subtypes?

The debate also happens when we try to categorize ideas, not just things. Logical fallacies are a great example. You may hear of very specific logical fallacies, such as the “argument ad Hitlerum”, which is an attempt to refute an argument by tying it somehow to something Hitler did, said, or believed. But really this is just a specific instance of a “poisoning the well” logical fallacy. Does it really deserve its own name? But it’s so common it may be worth pointing out as a specific case. In my opinion, whatever system is most useful is the one we should use, and in many cases that’s the one that facilitates understanding. Knowing how different logical fallacies are related helps us truly understand them, rather than just memorize them.

A recent paper enters the “lumper vs splitter” fray with respect to cognitive biases. They do not frame their proposal in these terms, but it’s the same idea. The paper is – Toward Parsimony in Bias Research: A Proposed Common Framework of Belief-Consistent Information Processing for a Set of Biases. The idea of parsimony is to use to be economical or frugal, which often is used to apply to money but also applies to ideas and labels. They are saying that we should attempt to lump different specific cognitive biases into categories that represent underlying unifying cognitive processes.

Continue Reading »

Feb

16

2023

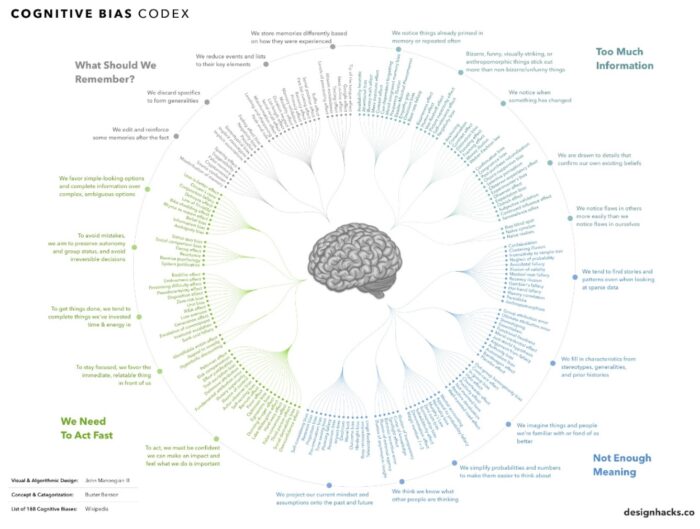

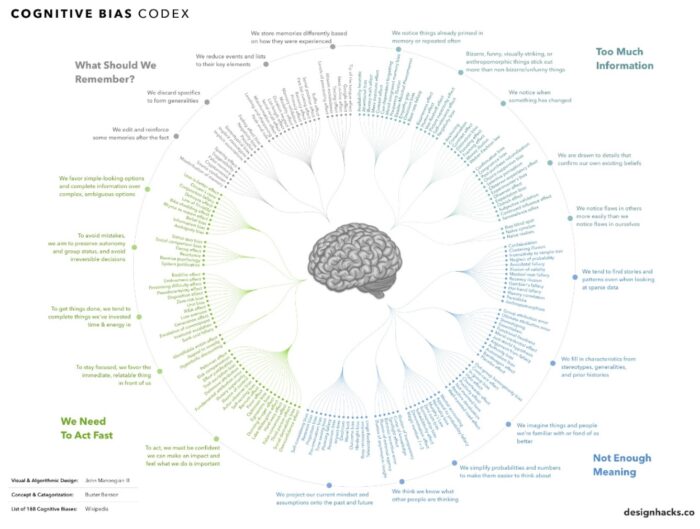

As I have discussed numerous times on this blog, our brains did not evolve to be optimal precise perceivers and processors of information. Here is an infographic showing 188 documents cognitive biases. These biases are not all bad – they are tradeoffs. Evolutionary forces care only about survival, and so the idea is that many of these biases are more adaptive than accurate. We may, for example, overcall risk because avoiding risk has an adaptive benefit. Not all of the biases have to be adaptive. Some may be epiphenomena, or themselves tradeoffs – a side effect of another adaptation. Our visual perception is rife with such tradeoffs, emphasizing movements, edges, and change at the expense of accuracy and the occasional optical illusion.

As I have discussed numerous times on this blog, our brains did not evolve to be optimal precise perceivers and processors of information. Here is an infographic showing 188 documents cognitive biases. These biases are not all bad – they are tradeoffs. Evolutionary forces care only about survival, and so the idea is that many of these biases are more adaptive than accurate. We may, for example, overcall risk because avoiding risk has an adaptive benefit. Not all of the biases have to be adaptive. Some may be epiphenomena, or themselves tradeoffs – a side effect of another adaptation. Our visual perception is rife with such tradeoffs, emphasizing movements, edges, and change at the expense of accuracy and the occasional optical illusion.

One interesting perceptual bias is called serial dependence bias – what we see is influenced by what we recently saw (or heard). It’s as if one perception primes us and influences the next. It’s easy to see how this could be adaptive. If you see a wolf in the distance, your perception is now primed to see wolves. This bias may also benefit in pattern recognition, making patterns easier to detect. Of course, pattern recognition is one of the biggest perceptual biases in humans. Our brains are biased towards detecting potential patterns, way over calling possible patterns, and then filtering out the false positives at the back end. Perhaps serial perceptual bias is also part of this hyper-pattern recognition system.

Psychologists have an important question about serial dependence bias, however. Does this bias occur at the perceptual level (such as visual processing) or at a higher cognitive level? A recently published study attempted to address this question. They exposed subjects to an image of coins for half a second (the study is Japanese, so both the subjects and coins were Japanese). They then asked subjects to estimate the number of coins they just saw and their total monetary value. The researchers wanted to know what had a greater effect on the subjects – the previous amount of coins they had just viewed or their most recent guess. The idea is that if serial dependence bias is primarily perceptual, then the amount of coins will be what affects their subsequent guesses. If the bias is primarily a higher cognitive phenomenon, then their previous guesses will have a greater effect than the actual amount they saw. To help separate the two (because higher guesses would tend to align with greater amounts) they had subjects estimate the number and value of coins on only every other image. Therefore their most recent guess would be different than the most recent image they saw.

Continue Reading »

Jun

17

2022

Human nature (and it’s pretty clear that we do have a nature) is complex and multifaceted. We have multiple tendencies, biases, and heuristics all operating at once, pulling us in different directions. These tendencies also interact with our culture and environment, so we are not a slave to our biases. We can understand and rise above them, and we can develop norms, culture, and institutions to nurture our better aspects and mitigate our dark side. That is basically civilization in a nutshell.

Human nature (and it’s pretty clear that we do have a nature) is complex and multifaceted. We have multiple tendencies, biases, and heuristics all operating at once, pulling us in different directions. These tendencies also interact with our culture and environment, so we are not a slave to our biases. We can understand and rise above them, and we can develop norms, culture, and institutions to nurture our better aspects and mitigate our dark side. That is basically civilization in a nutshell.

In fact, many scientists believe that humans also domesticated themselves – applied selection pressures that favored people who were less aggressive, more pro-social. It’s hard to prove this is true, but it does make sense. As civilization took hold, people whose temperament were better suited to that civilization would have a survival advantage.

Psychologists, however, have long documented that pro-social behavior in humans is a double-edged sword, because we only appear to be pro-social toward our perceived in-group. Toward those who we believe to be members of an out-group the cognitive algorithm flips. This is referred to as in-group bias, and also as “tribalism” (not meant as a knock against any traditional tribal culture). Negativity toward a perceived out-group can be extreme, even to the point of dehumanizing out-group members – depriving them of their basic humanity, and therefore any moral obligation to them. That appears to be how our brains reconcile these conflicting impulses. Evolutionary forces favored people who had a sense of justice, fairness, and compassion, but also needed a way to suspend these emotions when our group was fighting for its survival against a rival group. At least those groups with the most intense in-group loyalty, and the ability to brutalize members of an outgroup, were the ones that survived and are therefore our ancestors.

Increasingly neuroscience can investigate the neuroanatomical correlates of psychologically documented phenomena. In other words, psychologists show how people behave, and then neuroscientists can investigate what’s happening in the brain when they behave that way. A recent study looks at one possible neural mechanism for in-group bias. They recruited male subjects from the same university and then imaged their brain activity while they retaliated in a game against targets from their university and targets from a rival university. The researchers used rival universities, rather than more deeply held group identities (such as nationality, race, religion, political affiliation) to avoid undue stress on the subjects. Yet even with what they considered to be a mild group identity, the subjects showed greater activity in the ventral striatum when retaliating against out-group targets than in-group targets.

Continue Reading »

May

19

2022

Having a working understanding of the biases and heuristics that our brains use to make sense of the world is critical to neuropsychological humility and metacognition. They also help use make better sense of the world, and therefore make better decisions. Here’s a fun example. Let’s say you increase your driving speed from 40 mph to 60 mph over a 100 mile journey. How much would you need to increase your speed from a starting point of 80 mph in order to save the same amount of time on the journey? Is it 100 mph or 120 mph?

Having a working understanding of the biases and heuristics that our brains use to make sense of the world is critical to neuropsychological humility and metacognition. They also help use make better sense of the world, and therefore make better decisions. Here’s a fun example. Let’s say you increase your driving speed from 40 mph to 60 mph over a 100 mile journey. How much would you need to increase your speed from a starting point of 80 mph in order to save the same amount of time on the journey? Is it 100 mph or 120 mph?

Many people follow the linear bias, the false assumption that most systems follow a linear path. It is an interesting question as to why this bias is so deeply rooted in human psychology, but research shows that it is. Others may follow the ratio heuristic, and consider that 60 mph is 50% more than 40 mph so you would have to increase your speed to 120 mph to get the same 50% increase. But this too is wrong. The real answer is 240 mph. Do the math for yourself. While the ratio heuristic seems more reasonable, in this context it fails because you are not considering the fact that at higher speeds the overall trip time is less and therefore the potential time saving is also less.

When the linear and ratio biases are applied to time, in fact, psychologists refer to this as the time-saving bias. We tend to underestimate how much time we can save when starting at a slow speed and vastly overestimate time saving when starting at a relatively high speed. This bias applies to more than just driving, but also to any task. We feel that if we push our speed or efficiency higher, there will be substantial gains, but there usually isn’t. At the same time, we need to realize that bottlenecks where speed is very low present an opportunity for significant increases in efficiency. We know this, but we still tend to underestimate its effects, especially relative to increasing already high speeds.

So in any operation, whether driving on a journey, completing a task at work, or maximizing the efficiency of a factory, it is best to focus on the slowest components. There is significantly diminishing returns when improving already fast processes, and they are probably not worth it.

Continue Reading »

May

28

2020

Human thought processes are powerful but flawed, like a GPS system that uses broken algorithms to lead you to the wrong destination. Psychologists study these cognitive biases and heuristic patterns of thought to better understand these flaws and propose possible fixes to mitigate them. To a large degree, scientific skepticism is about exactly that – identifying and compensating for the flaws in human cognition.

Human thought processes are powerful but flawed, like a GPS system that uses broken algorithms to lead you to the wrong destination. Psychologists study these cognitive biases and heuristic patterns of thought to better understand these flaws and propose possible fixes to mitigate them. To a large degree, scientific skepticism is about exactly that – identifying and compensating for the flaws in human cognition.

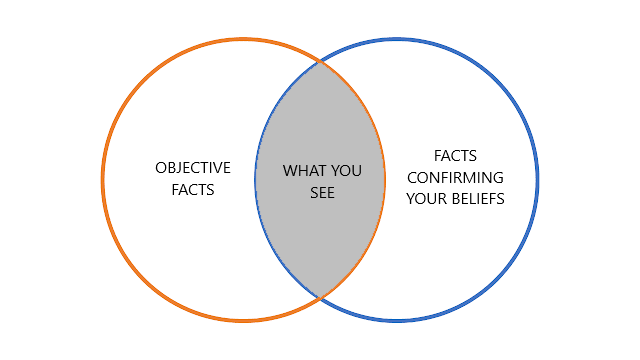

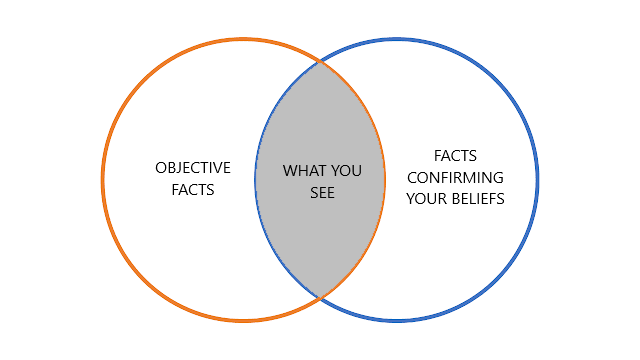

Perhaps the mother of all cognitive biases is confirmation bias, the tendency to notice, accept, and remember information that confirms what we already believe (or perhaps want to believe), and to ignore, reject, or forget information that contradicts what we believe. Confirmation bias is an invisible force, constantly working in the background as we go about our day, gathering information and refining our models of reality. But unfortunately it does not lead us to accuracy or objective information. It drives us down the road of our own preexisting narratives.

One of the things that makes confirmation bias so powerful is that it gives us the illusion of knowledge, which falsely increases our confidence in our narratives. We think there is a ton of evidence to support our beliefs, and anyone who denies them is blind, ignorant, or foolish. But that evidence was selectively culled from a much larger set of evidence that may tell a very different story from the one we see. It’s like reading a book but making up your own story by only reading selective words, and stringing them together in a different narrative.

A new study adds more information to our understanding of confirmation bias. It not only confirms our selective processing of confirming information, it shows that confidence drives this process. So not only does confirmation bias lead to false confidence, that confidence then drives more confirmation bias in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Continue Reading »

Sep

23

2019

One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic.

One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic.

This general phenomenon is not limited to medical pseudoscience, and I think it applies broadly. We may be unaware of a problem, but once we learn to recognize it we see it everywhere. Confirmation bias kicks in, and we initially overapply the lessons we recently learned.

I have this problem when I give skeptical lectures. I can spend an hour discussing publication bias, researcher bias, p-hacking, the statistics about error in scientific publications, and all the problems with scientific journals. At first I was a little surprised at the questions I would get, expressing overall nihilism toward science in general. I inadvertently gave the wrong impression by failing to properly balance the lecture. These are all challenges to good science, but good science can and does get done. It’s just harder than many people think.

This relates to Aristotle’s philosophy of the mean – virtue is often a balance between two extreme vices. Similarly, I find there is often a nuanced position on many topics balanced precariously between two extremes. We can neither trust science and scientists explicitly, nor should we dismiss all of science as hopelessly biased and flawed. Freedom of speech is critical for democracy, but that does not mean freedom from the consequences of your speech, or that everyone has a right to any venue they choose.

A recent Guardian article about our current post-truth world reminded me of this philosophy of the mean. To a certain extent, society has gone from one extreme to the other when it comes to facts, expertise, and trusting authoritative sources. This is a massive oversimplification, and of course there have always been people everywhere along this spectrum. But there does seem to have been a shift. In the pre-social media age most people obtained their news from mainstream sources that were curated and edited. Talking head experts were basically trusted, and at least the broad center had a source of shared facts from which to debate.

Continue Reading »

Jul

19

2018

I have discussed a number of cognitive biases over the years, based mostly on research in adults. For example, Kahneman and Tversky first proposed the representativeness heuristic in 1973. But at what age do children start using this heuristic?

I have discussed a number of cognitive biases over the years, based mostly on research in adults. For example, Kahneman and Tversky first proposed the representativeness heuristic in 1973. But at what age do children start using this heuristic?

A heuristic is essentially a mental short cut. Such short cuts are efficient, and decrease our cognitive load, but they are imperfect and prone to error. In the representativeness heuristic we rely on social information and ignore numerical information when making probability judgments about people.

In the classic experiment subjects were given a description of the personality of a student, designed to be a stereotype of an engineer. They were then asked how likely it was that the student was an engineering student. Many subjects answered that the student was likely an engineering student, without considering the base rate – the percentage of students who are in engineering. Even when given that information showing it was unlikely the student was an engineer, many subjects ignored the numerical information and based their judgments entirely on the social information.

This can also be seen in the context of general cognitive styles – intuitive vs analytical (or thinking fast vs thinking slow – as in the title of Kahneman’s book). Intuitive thinking is our gut reaction, it is quick and relies heavily on social cues and pattern recognition. It is therefore fast, but is also error prone and subject to a host of cognitive biases.

Continue Reading »

Nov

03

2017

“Oceania was at war with Eurasia; therefore Oceania had always been at war with Eurasia.”

– George Orwell

In Orwell’s classic book, 1984, the totalitarian state controlled information and they used that power to obsessively manage public perception. One perception they insisted upon was that the state was consistent – never changing its mind or contradicting itself. This desire, in turn, is based on the premise that changing one’s mind is a sign of weakness. It is an admission of prior error or fault.

In Orwell’s classic book, 1984, the totalitarian state controlled information and they used that power to obsessively manage public perception. One perception they insisted upon was that the state was consistent – never changing its mind or contradicting itself. This desire, in turn, is based on the premise that changing one’s mind is a sign of weakness. It is an admission of prior error or fault.

Unsurprisingly our perceptions of our own prior beliefs are biased in order to minimize apparent change, a recent study shows. The exact reason for this bias was not part of the study.

Researchers surveyed subjects as to their beliefs regarding the effectiveness of corporal punishment for children. This topic was chosen based on the assumption that most subjects would have little knowledge of the actual literature and would not have strongly held beliefs. Subjects were then given articles to read making the case for the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of spanking (either consistent with or contrary to their prior beliefs), and then their beliefs were surveyed again.

Continue Reading »

Jun

01

2017

The human brain is plagued with cognitive biases – flaws in how we process information that cause our conclusions to deviate from the most accurate description of reality possible with available evidence. This should be obvious to anyone who interacts with other human beings, especially on hot topics such as politics or religion. You will see such biases at work if you peruse the comments to this blog, which is rather a tame corner of the social media world.

The human brain is plagued with cognitive biases – flaws in how we process information that cause our conclusions to deviate from the most accurate description of reality possible with available evidence. This should be obvious to anyone who interacts with other human beings, especially on hot topics such as politics or religion. You will see such biases at work if you peruse the comments to this blog, which is rather a tame corner of the social media world.

Of course most people assume that they are correct and everyone who disagrees with them is crazy, but that is just another bias.

The ruler of all cognitive biases, in my opinion, is confirmation bias. This is a tendency to notice, accept, and remember information which appears to support an existing belief and to ignore, distort, explain away, or forget information which seems to disconfirm an existing belief. This process works undetected in the background to create the powerful illusion that the facts support our beliefs.

If you are not aware of confirmation bias and do not take active steps to avoid it, it will have a dramatic effect on your perception of reality. Continue Reading »

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess. As I have discussed numerous times on this blog, our brains did not evolve to be optimal precise perceivers and processors of information.

As I have discussed numerous times on this blog, our brains did not evolve to be optimal precise perceivers and processors of information.  Human nature (and it’s pretty clear that we do have a nature) is complex and multifaceted. We have multiple tendencies, biases, and heuristics all operating at once, pulling us in different directions. These tendencies also interact with our culture and environment, so we are not a slave to our biases. We can understand and rise above them, and we can develop norms, culture, and institutions to nurture our better aspects and mitigate our dark side. That is basically civilization in a nutshell.

Human nature (and it’s pretty clear that we do have a nature) is complex and multifaceted. We have multiple tendencies, biases, and heuristics all operating at once, pulling us in different directions. These tendencies also interact with our culture and environment, so we are not a slave to our biases. We can understand and rise above them, and we can develop norms, culture, and institutions to nurture our better aspects and mitigate our dark side. That is basically civilization in a nutshell. Having a working understanding of the biases and heuristics that our brains use to make sense of the world is critical to neuropsychological humility and metacognition. They also help use make better sense of the world, and therefore make better decisions. Here’s a fun example. Let’s say you increase your driving speed from 40 mph to 60 mph over a 100 mile journey. How much would you need to increase your speed from a starting point of 80 mph in order to save the same amount of time on the journey? Is it 100 mph or 120 mph?

Having a working understanding of the biases and heuristics that our brains use to make sense of the world is critical to neuropsychological humility and metacognition. They also help use make better sense of the world, and therefore make better decisions. Here’s a fun example. Let’s say you increase your driving speed from 40 mph to 60 mph over a 100 mile journey. How much would you need to increase your speed from a starting point of 80 mph in order to save the same amount of time on the journey? Is it 100 mph or 120 mph? Human thought processes are powerful but flawed, like a GPS system that uses broken algorithms to lead you to the wrong destination. Psychologists study these cognitive biases and heuristic patterns of thought to better understand these flaws and propose possible fixes to mitigate them. To a large degree, scientific skepticism is about exactly that – identifying and compensating for the flaws in human cognition.

Human thought processes are powerful but flawed, like a GPS system that uses broken algorithms to lead you to the wrong destination. Psychologists study these cognitive biases and heuristic patterns of thought to better understand these flaws and propose possible fixes to mitigate them. To a large degree, scientific skepticism is about exactly that – identifying and compensating for the flaws in human cognition. One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic.

One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic. I have discussed a number of cognitive biases over the years, based mostly on research in adults. For example, Kahneman and Tversky first proposed the representativeness heuristic in 1973. But at what age do children start using this heuristic?

I have discussed a number of cognitive biases over the years, based mostly on research in adults. For example, Kahneman and Tversky first proposed the representativeness heuristic in 1973. But at what age do children start using this heuristic? In Orwell’s classic book, 1984, the totalitarian state controlled information and they used that power to obsessively manage public perception. One perception they insisted upon was that the state was consistent – never changing its mind or contradicting itself. This desire, in turn, is based on the premise that changing one’s mind is a sign of weakness. It is an admission of prior error or fault.

In Orwell’s classic book, 1984, the totalitarian state controlled information and they used that power to obsessively manage public perception. One perception they insisted upon was that the state was consistent – never changing its mind or contradicting itself. This desire, in turn, is based on the premise that changing one’s mind is a sign of weakness. It is an admission of prior error or fault. The human brain is plagued with cognitive biases – flaws in how we process information that cause our conclusions to deviate from the most accurate description of reality possible with available evidence. This should be obvious to anyone who interacts with other human beings, especially on hot topics such as politics or religion. You will see such biases at work if you peruse the comments to this blog, which is rather a tame corner of the social media world.

The human brain is plagued with cognitive biases – flaws in how we process information that cause our conclusions to deviate from the most accurate description of reality possible with available evidence. This should be obvious to anyone who interacts with other human beings, especially on hot topics such as politics or religion. You will see such biases at work if you peruse the comments to this blog, which is rather a tame corner of the social media world.