Sep 03 2021

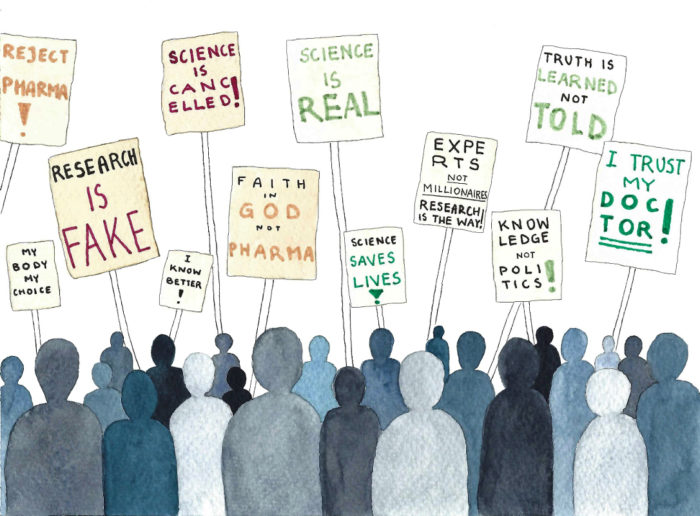

Trust in Science May Lead to Pseudoscience

The ultimate goal of scientific skepticism is to skillfully use a process that has the maximal probability of accepting claims that are actually true and rejecting those that are false, while suspending judgment when an answer is not available. This is an open-ended process and is never complete, although some conclusions are so solid that questioning them further requires an extremely high bar of evidence. There are many components to scientific skepticism, broadly contained within scientific literacy, critical thinking skills, and media savvy. Traditional science communication focuses on scientific literacy (the so-called knowledge deficit model), but in the last few decades there has been copious research showing that this approach is not only not sufficient when dealing with many false beliefs, it may even be counterproductive.

The ultimate goal of scientific skepticism is to skillfully use a process that has the maximal probability of accepting claims that are actually true and rejecting those that are false, while suspending judgment when an answer is not available. This is an open-ended process and is never complete, although some conclusions are so solid that questioning them further requires an extremely high bar of evidence. There are many components to scientific skepticism, broadly contained within scientific literacy, critical thinking skills, and media savvy. Traditional science communication focuses on scientific literacy (the so-called knowledge deficit model), but in the last few decades there has been copious research showing that this approach is not only not sufficient when dealing with many false beliefs, it may even be counterproductive.

A new study offer more evidence to support this view, highlighting the need to combine scientific literacy with critical thinking in order to combat misinformation and false claims. The study focuses on the effect of trust in science as an independent variable, and combined with the ability to critically evaluate scientific evidence. In a series of four experiments they looked at acceptance of false claims regarding either a fictional virus, or false claims about GMOs and tumors:

Depending on experimental condition, however, the claims contained references to either (a) scientific concepts and scientists who claimed to have conducted research on the virus or GMOs (scientific content), or (b) lay descriptions of the same issues from activist sources (no scientific content).

They wanted to see the effect of citing scientists and research on the acceptance of the false claims. As predicted, referring to science or scientists increased acceptance. They found that subjects who scored higher in terms of trust in science were more likely to believe false claims when scientists were cited – so trust in science made them more vulnerable to pseudoscience. For those with low trust in science, the presence or absence of scientific content had no effect on their belief in the false claims. These results replicated in the first three studies, using the fictional virus and the GMO claims.

In all these experiments there was a negative correlation between belief in the false claims and “methodological literacy” – which is the ability to critically analyze data.

In the fourth experiment they tested the effect of “inducing critical evaluation”. They had three groups, one engaging in an exercise in which they have to give examples of situations where they had to question authority and think for themselves – “Please name 3 examples of people needing to think for themselves and not blindly trust what media or other sources tell them. This could be regarding science or any type of information, either from history, current events, or your personal life” In the second the recounted the benefits of science – “Please name 3 examples of science saving lives or otherwise benefiting humanity. This could be in the medical sciences or chemistry, physics, or any type of science.” situations where they trusted scientific expertise. The third was a control group asked to think about landscapes. In this experiment the critical thinking mindset group had reduced belief in the false information regardless of whether or not it was presented with scientific references.

What all this means (combined with other research, which the article reviews), is that trust in science itself, while a good thing overall, makes people more susceptible to pseudoscientific manipulation. All you have to do is make a claim seem sciency by quoting an alleged expert or citing a study (regardless of the quality, relevance, or representativeness of that study), and those with trust in science will see that as a cue to trust the claims being made.

Overall I think this means that when dealing with noncontroversial claims by legitimate scientists, trust in science is a good thing. It makes people more likely to accept claims and conclusions which are likely to be true because they are backed by legitimate science. But when dealing with pseudoscience, science denial, or claims that are controversial because they have political or ideological implications, this trust in science can be exploited to increase belief in and dissemination of false claims.

This effect, however, can be mitigated in a number of ways. The study focuses on methodological literacy, which is one aspect of critical thinking. This is the ability to read scientific information and evaluate it for quality and relevance, to see if the conclusions flow from the data, and to see if the conclusions actually support the claim for which it is being cited. There are obviously levels here, from basic understanding to deep technical expertise. But having even a basic methodological understanding can be helpful

Other aspects of critical thinking (not looked at in this study) include understanding the nature of bias, cognitive styles, and heuristics and understanding logical fallacies and the structure of sound arguments. It also involves knowing the nature of pseudoscience and science denial, and how they distort the process of science in order to reach a desired but unreliable conclusion.

Balancing all of this can be tricky, and we are seeing this played out here in this blog with the many topics of discussion. It’s easy to argue for not trusting authorities and evaluating claims for oneself, but it is easy to distort this process to simply reject valid science one doesn’t like, and to substitute your own biases for reliable scientific conclusions. Some topics require a fairly high degree of methodological literacy, combined with high levels of critical thinking skills and specific topic expertise.

In the end there is also not substitute for the twin virtues of humility and trying as hard as possible to be unbiased. We have to value following a valid scientific process over any particular conclusion, and be willing to admit error and change our position in light of new evidence and arguments. All the cognitive skills in the world will not matter if we are motivated enough to cling to a particular narrative or belief.