Sep 29 2011

Race and Perception

A new study finds that the way people dress affect our perception of their race. At least, that is what the authors and the press release claim.

The basic concept makes sense in light of what we have learned about perception. Human perception is a highly constructed phenomenon – we do not have a camera in our heads that passively records the outside world. At every level what we think we see is highly filtered, enhanced, and interpreted by our brains to construct a meaningful (but not necessarily accurate) image of the world.

These processes occur at the most basic level – enhancing edges and contrast, perceiving color and motion; and also at more sophisticated levels – interpreting three-dimensionality and therefore size and distance. But also at the highest levels of perception – putting it all together as a meaningful object and scene, and imbuing not only meaning but emotion onto what we see.

Perception is also processed in terms of temporal synchronization. It takes different amounts of time for sound and light to reach us, and for our brains to process that information, and yet when someone claps their hands near us the sight and sound seem perfectly synchronized. As long as the two sensations are within 80ms of each other, they will be perceived as simultaneous – our brains tweak the time perception to make them match. But if the two sensation are separated by more than 80ms they will seem out of sync. The transition is also abrupt.

Further, the images we see are compared to our internal model of reality. We search for matches and meaning in what we see – is that a human face, if so, who? The visual stream is also compared to the other senses, and even modified to bring them all into line.

A dramatic example of this is the comparison of what we hear to how a person’s lips are moving to create the perception of what letters they are saying. This is known as the Mcgurk effect, and can be quite stunning.

Another example of this is gender perception, which is affected by a person’s voice. This effect is most dramatic the more ambiguous a person’s gender by sight alone. It therefore makes perfect sense that race perception will also be affected by multiple variables, and the effect of these other variables will be most dramatic with ambiguous stimuli. I was therefore prepared to believe the results of this study. But let’s see what the study actually found.

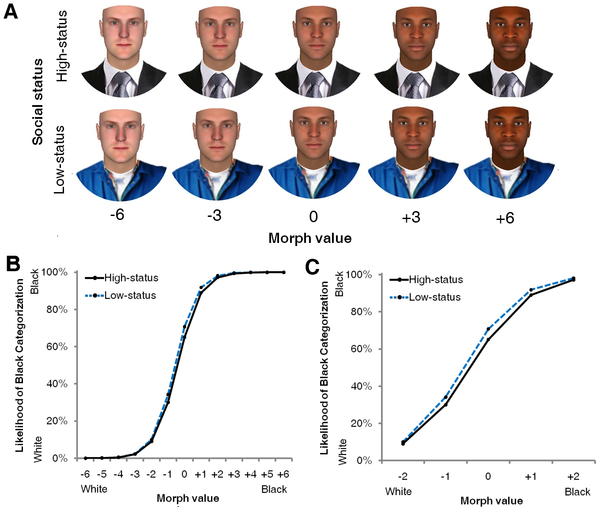

Subjects were asked to look at pictures of people and determine whether they were caucasian or African – a forced binary choice. The pictures were a morphed composite, and ranged from unambiguously caucasian at one end to unambiguously African at the other. In the middle the picture was therefore maximally ambiguous for race. The same pictures were either dressed in a suit or in coveralls (high status and low status attire). The authors conclude:

Together, the findings show how stereotypes interact with physical cues to shape person categorization, and suggest that social and contextual factors guide the perception of race.

But let takes a closer look a the data. Here is it plotted by the two factors, racial morph and attire:

On the left is the entire data set. As you can see, the effect of attire is barely perceptible. The authors zoom in on the data in the right plot to show the effect. For the most ambiguous racial morph the effect of attire was to raise the probability of a black categorization from 61-65% – a 4% increase. This result was barely statistically significant at P<0.05. What is remarkable is how tiny the effect is – if it is even real, given that it is barely significant.

The authors also did a follow up experiment in which they tracked mouse movements of the subjects, and they found that even in cases where the subject categorized a picture with low-status attire as white, the mouse temporarily moved toward the black choice. They conclude that we have different racial categorization schemes, one based upon facial characteristics but another based upon racial stereotypes, like social status. What they are seeing with the mouse movements are conflicts between these two systems, revealing the influence of the social stereotype.

These conclusions may be correct – they are plausible and as I said above they match what we are discovering about how our brains construct perception. But I was struck by the complete absence of any mention in the study or the press coverage about how tiny the effect size is. To me it not only calls into question the effect itself, but also (if real) its significance. I think this warranted some discussion. Even when the authors discuss the limitations of the study, there is no mention of the impact of this small effect size on their interpretation. In my opinion, they could have easily concluded that there is no significant influence of social status on race perception.

This reflects, in my opinion, a confusion of statistically significant with clinically significant. Just because a result ekes over the statistically significant line does not mean that the effect size itself is significant – both factors should be considered when interpreting the results.

So while the results are plausible, I am not impressed and will withhold judgment until the results are replicated.