Jan 24 2017

More Evidence Autism Rates Not Truly Increasing

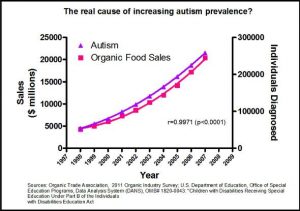

One of the pillars of the anti-vaccine movement over the last two decades is that we are in the midst of an “autism epidemic” because autism incidence has dramatically increased over this time. This increase calls for an explanation, which, of course, they believe must have something to do with vaccines.

One of the pillars of the anti-vaccine movement over the last two decades is that we are in the midst of an “autism epidemic” because autism incidence has dramatically increased over this time. This increase calls for an explanation, which, of course, they believe must have something to do with vaccines.

Like all beliefs and movements disconnected from real science, this is a simplistic and invalid approach to a complex science, in this case epidemiology.

In medicine we are very interested in how disease rates change over historical time, and among various locations and demographics. Such information provides critical clues to the etiology (causes) of disease and the effects of various risk factors and treatments. There are many things that can change the incidence (new diagnoses over time) and prevalence (number of people with a diagnosis at any one point in time) of a disease, including the way we make and record such diagnoses.

This is always the critical question when following disease incidence over time – are there any artifacts in how we are collecting data. Are the changes in the numbers reflecting a real biological change in the population, or just a change in the behavior of physicians?

Those who warn about an “autism epidemic” are not asking these questions. They are taking the numbers at face value, because they serve a rhetorical purpose.

Meanwhile, scientists have been asking the right questions. What they have found is that, over the last few decades, diagnostic patterns of autism have indeed changed. They have identified a few specific changes that would lead to an increase in the incidence of autism diagnoses without any change biologically in the true incidence of the condition.

First, awareness of autism has dramatically increased, among parents, teachers, and doctors. Increased awareness leads to increased diagnoses. Because autism is more and more covered by state-provided services, there is also an incentive to seek out the diagnosis.

The diagnostic criteria have also been broadened. This is the most common artifact affecting incidence numbers. Whenever we make changes to the criteria necessary to establish a diagnosis, it can have a dramatic affect on the incidence.

There is also something called diagnostic substitution. In the past children with the same constellation of symptoms would have been labeled as having a language disorder, or a non-specific developmental disorder, and now they are diagnosed with autism.

So, epidemiologists have done a number of studies, using different methods, to evaluate the true incidence of autism. One way to get at this is to compare patient populations over time using the exact same diagnostic criteria. You can even look back in time if you have adequate records. One such study, published in 2015, found:

In 2010 there were an estimated 52 million cases of ASDs, equating to a prevalence of 7.6 per 1000 or one in 132 persons. After accounting for methodological variations, there was no clear evidence of a change in prevalence for autistic disorder or other ASDs between 1990 and 2010. Worldwide, there was little regional variation in the prevalence of ASDs.

A 2006 review of studies looking at diagnostic behavior found:

The recorded prevalence of autism has increased considerably in recent years. This reflects greater recognition, with changes in diagnostic practice associated with more trained diagnosticians; broadening of diagnostic criteria to include a spectrum of disorder; a greater willingness by parents and educationalists to accept the label (in part because of entitlement to services); and better recording systems, among other factors.

A 2013 study found that there are spatial clusters in autism diagnoses, meaning that if a family lives near another family with a member diagnosed with autism they were more likely to also have sought a diagnosis. The pattern did not just follow physical closeness, but social networking.

A 2009 study found significant diagnostic substitution accounting for 25% of the increase in autism diagnoses.

There is similar evidence from other countries. A 2015 Danish study found that 60% of the increase in autism diagnoses could be specifically accounted for by changes in diagnostic patterns.

Now a new study out of Australia adds to the pile of evidence by taking a slightly different approach to the question. They reviewed records of 1252 children from 2000-2009, over a time when consistent diagnostic methods were used, and found that over time the severity of diagnoses had decreased. This means that doctors were diagnoses less severe cases with autism. This, of course, would result in a significant increase in the incidence of new diagnoses.

Conclusion

Taken together the literature clearly demonstrates that the majority of the increase in autism diagnoses can be accounted for by loosening the diagnostic criteria, increased surveillance, and diagnostic substitution. It is possible these factors account for 100% of the increase, which is suggested by those studies that find a stable incidence over time when consistent diagnostic methods are used.

The data is not able to completely rule out that there is also a small real increase in the incidence of autism, but a real increase is not necessary to explain the data.

What is clearly true is that there is no autism epidemic, and therefore any attempts to explain the non-existent epidemic are doomed to failure.