Feb 26 2016

Mitochondrial Replacement Therapies

Another innovative medical technology is on the brink of being applied to actual patients, and it is spawning the typical discussion about the ethics of altering human biology. I think this will likely take the usual course.

Another innovative medical technology is on the brink of being applied to actual patients, and it is spawning the typical discussion about the ethics of altering human biology. I think this will likely take the usual course.

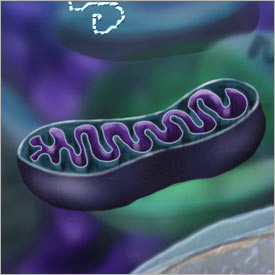

The technology is mitochondrial replacement therapies (MRTs). Mitochondria are organelles inside every cell. They are the power plants of cells, burning fuel with oxygen to create ATP, which are molecules that provide energy for all the processes of life.

Interestingly, mitochondria probably derived from independent cells that evolved a symbiotic relationship with eukaryotic cells. They are like bacteria living inside each cell with a specialized function of making ATP.

Mitochondria still retain some of their own DNA, which is partly how we know they were once independent organisms. Mitochondria contain 17,000 base pairs and just 37 genes (compared to 20,000 genes in human nuclear DNA). Over millions of years of evolution they have also outsourced some of their DNA to the nuclear DNA of cells, but also still retain some of their own DNA. Not only does this mitochondrial DNA affect the functioning of the mitochondria itself, it has implications for overall cell function through its interaction with nuclear DNA.

There is a class of diseases known as mitochondrial disorders that result from harmful mutations of the mitochondrial DNA. These diseases can be quite devastating, which is not surprising given how critical mitochondrial function is to every cell.

Also, mitochondria are almost exclusively inherited from the mother, because eggs are large cells that contain mitochondria and other organelles, while sperm are stripped down DNA delivery systems that contain few or no mitochondria.

This situation creates an opportunity to prevent the inheritance of harmful mitochondrial mutations, and that is where MRTs comes in. Essentially these techniques involve taking mitochondria from a healthy donor and combining it with the nuclear DNA of the mother during in-vitro fertilization. This technique results in so-called “three parent babies.”

MRTs were recently approved in the UK, and the US is also considering approving human trials of MRTs. Thus begins the ethical discussions.

One concern is safety. This is, of course, a perfectly reasonable concern for any new medical technology. One interesting specific concern is mitochondrial-nuclear mismatch. Mitochondrial DNA and nuclear DNA evolve together, and they interact affecting the overall health of the cell. Some researchers have found that when certain populations of the same species are bred together the offspring are unhealthy due to a mismatch between their nuclear and mitochondrial DNA.

The question is – how much does this mismatch affect apply to humans? Will the nuclear DNA from one woman always play nice with the mitochondrial DNA of another when combined in the same cell? Not all scientists are worried this will be a problem in humans. Others feel we should match donors and recipients so that they have the same basic mitochondrial type (called a haplotype).

In any case, research will need to confirm the safety of MRTs in humans. That I consider to be completely standard.

Others have raised ethical concerns regarding some specific techniques that require destroying an embryo in the process. However, this is a generic concern for IVF, which inevitably involves destroying unused or less healthy embryos. I don’t see this as an eventual stumbling block.

Another concern is that changes to mitochondrial DNA can affect the germ line, meaning that they can be perpetuated in offspring and therefore change the genetics of future human populations. This is only a concern if the technique used damages or alters the donor mitochondrial DNA. It seems research will quell this concern. Meanwhile some have called for early research to produce only male children, who will not perpetuate the mitochondrial DNA.

The final category of ethical concerns is over the psychological and social impact of having three parents. While I would not ignore these concerns, they also don’t worry me. If history is any guide these kinds of concerns rapidly fade once the benefits of a new technology are fully realized.

I think that the history of IVF is a reliable guide to how this generally plays out. People are uncomfortable with a new medical technology that challenges our quaint notions of what is “natural” and about the “sanctity” of the human body. They will complain about putting animal parts in humans, putting machine parts in humans, altering anatomy, and seem especially squishy about altering genetics.

From my point of view these reactions all stem from a basic uncomfortableness with the reality that we are just meat machines. We are biological machines that can break down, and can be altered and manipulated without theoretical limit (the only limits are practical and related to our current technology).

People do incrementally become more comfortable with the implications of this undeniable reality when a new medical technique provides tangible benefits. When parents can have children free from mitochondrial disease, the technology will be embraced.

I think this is and will continue to be a general trend. When stem cells start curing loved-ones, everyone will forget that they were ever controversial. No one bats an eye at IVF today, and no one will bat an eye at mitochondrial therapy tomorrow.