May 28 2020

Confidence Drives Confirmation Bias

Human thought processes are powerful but flawed, like a GPS system that uses broken algorithms to lead you to the wrong destination. Psychologists study these cognitive biases and heuristic patterns of thought to better understand these flaws and propose possible fixes to mitigate them. To a large degree, scientific skepticism is about exactly that – identifying and compensating for the flaws in human cognition.

Human thought processes are powerful but flawed, like a GPS system that uses broken algorithms to lead you to the wrong destination. Psychologists study these cognitive biases and heuristic patterns of thought to better understand these flaws and propose possible fixes to mitigate them. To a large degree, scientific skepticism is about exactly that – identifying and compensating for the flaws in human cognition.

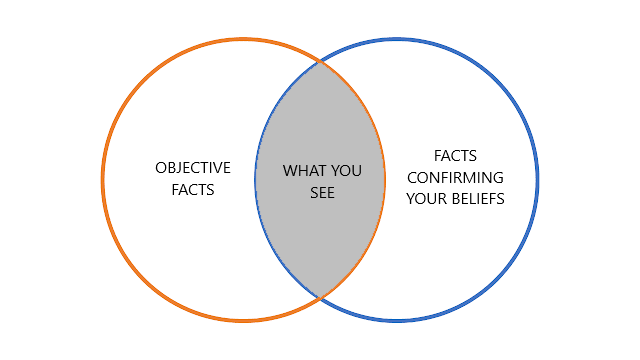

Perhaps the mother of all cognitive biases is confirmation bias, the tendency to notice, accept, and remember information that confirms what we already believe (or perhaps want to believe), and to ignore, reject, or forget information that contradicts what we believe. Confirmation bias is an invisible force, constantly working in the background as we go about our day, gathering information and refining our models of reality. But unfortunately it does not lead us to accuracy or objective information. It drives us down the road of our own preexisting narratives.

One of the things that makes confirmation bias so powerful is that it gives us the illusion of knowledge, which falsely increases our confidence in our narratives. We think there is a ton of evidence to support our beliefs, and anyone who denies them is blind, ignorant, or foolish. But that evidence was selectively culled from a much larger set of evidence that may tell a very different story from the one we see. It’s like reading a book but making up your own story by only reading selective words, and stringing them together in a different narrative.

A new study adds more information to our understanding of confirmation bias. It not only confirms our selective processing of confirming information, it shows that confidence drives this process. So not only does confirmation bias lead to false confidence, that confidence then drives more confirmation bias in a self-reinforcing cycle.

The researchers use a simple computer system to test information processing (and make the point that prior literature supports the extrapolation from such simple decision-making to more complex decision-making). Subjects viewed dots that briefly appear on a screen. Many of the dots are moving in one direction, a minority are moving in the opposite direction, and another subset are moving randomly. The task is to determine the net movement of dots – to correctly perceive the correct direction in which the majority of dots are moving. For each subject the proportions were altered and calibrated so that subjects could be made more or less confident in their choice, while maintaining the same accuracy. Subjects then went through many trials indicating both the direction of movement (left or right) and a sliding scale of their confidence.

After a subject made their choice for one trial, they were shown another set of dots moving in the same direction (a so-called confirmatory trial) but easier to detect. They were then allowed to revise their initial choice. You can probably now see where this is going. Subjects who were initially incorrect and had a low level of confidence were able to revise their decision when presented with more obvious information. Those who were incorrect but with high confidence were less likely to revise their initial wrong choice when presented with more obvious information. Confidence had a negative effect on self correction.

That much is not surprising, but it is a clever way of demonstrating this effect. The next part of the study, however, is perhaps more interesting. Some of the trials were performed using magnetoencephalography (MEG) to view brain activity during the decision-making process. A particular area of the brain, the centro-parietal area, demonstrated activity (the centro-parietal event) when viewing the dots moving. This part of the brain is involved in information processing, so activity there makes sense for this task. However, when subjects were wrong with high confidence, they did not demonstrate a centro-parietal event when viewing subsequent disconfirming information. This suggests that confirmation bias partly works by not even processing information that goes against our current belief. The information is ignored.

That’s pretty powerful. We don’t even need to waste energy explaining away the information – we just never perceive it in the first place.

Obviously this is not the only mechanism of confirmation bias. Some information cannot be ignored. Prior studies suggest that the primary mechanism of confirmation bias is to rationalize away information that does not fit our model, and selectively forgetting such information or filing them away as “exceptions” to the rule. But in this paradigm, at least, we can also just filter out such information from our perception.

So – what do we do about it? Skepticism is not only about identifying biases but proposing fixes. Within the realm of science the primary compensatory mechanism is to use standardized rigorous methods which don’t allow for the influence of bias (such as double-blinding). Scientific studies must count all data, and not pick and choose. Methods must be determined at the beginning of the study, and not altered along the way. Failure to adhere to these rigorous methods allows confirmation bias to creep in, and invalidates the results.

But what about our day-to-day experience? We cannot live our lives as if we are in a rigorous scientific study. One of the primary fixes we can use to reduce the effects of confirmation bias is humility, and this study reinforces that. (I have previously referred to this as neuropsychological humility – a humility born out of an understanding of the limitations of our own brains.) This is also part of what we call metacognition – thinking about thinking itself. If we know that confirmation bias can lead us powerfully astray, then we need to be humble in our conclusion. We must always take the stance that we can be wrong. It also helps to place process and objective information above any particular conclusion.

This means that we don’t eliminate human emotions, but we understand them and make them work for us in a productive way. So, if we take pride in being humble, in not staking our claim in any rigid conclusion, in being flexible before new information, that gives us the emotional room to self-correct. There is no shame is saying, I was wrong, and in light of this new information, or new arguments or perspective, I will change my mind. In fact, changing one’s mind becomes a skeptical badge of honor.

This also highlights the pitfall of taking extreme ideological positions. Extreme ideologies tend to place a clean moral narrative above reality. While moderate positions tend to be born out of a tendency to see all sides, and admit strengths and weaknesses of various positions. This does not mean the “middle” position is always correct or superior – that is a misunderstanding of what it means to be moderate. A moderate position simply places facts and logic above ideology. Also, in many cases the “different sides” of an issue may be extremely asymmetrical. Sometimes one side is simply wrong. But rarely is the same side always wrong, and even when wrong may have legitimate points to make (even if they take them too far).

In a way to be moderate, to be humble and skeptical, is to position yourself as an outside objective referee. You cannot care which side wins, but instead you have to call balls and strikes as you see them. And if the instant replay shows you made a bad call, then you make a correction, and take pride in the fact that you were able to do so with humility.