Sep 14 2021

Cognitive Control and Cheating

It is a fundamental truth of human behavior that people sometimes cheat. And yet, we tend to have strong moral judgements against cheating, which leads to anti-cheating social pressure. How does this all play out in the human brain?

It is a fundamental truth of human behavior that people sometimes cheat. And yet, we tend to have strong moral judgements against cheating, which leads to anti-cheating social pressure. How does this all play out in the human brain?

Psychologists have tried to understand this within the standard neuroscience paradigm – that people have basic motivations mostly designed to meet fundamental needs, but we also have higher executive function that can strategically override these motivations. So the desire to cheat in order to secure some gain is countered by moral self-control, leading to an internal conflict (cognitive dissonance). We can resolve the dissonance in a number of ways. We can rationalize the morality in order to internally justify the desire to cheat, or we can suppress the desire to cheat and get a reward by feeling good about ourselves. Except experimentally most people do not fall at either end of the spectrum, but rather they cheat sometimes.

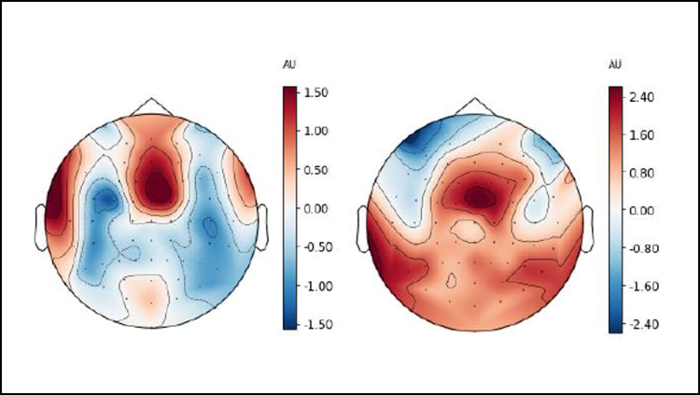

Recent research, however, has challenged this narrative, that cheating for gain is the default behavior and not cheating requires cognitive control. A new study replicates prior research showing that people differ in terms of their default behavior. Some people are mostly honest and only cheat a little, while others mostly cheat, and there is a continuum between. Perhaps even more interesting is that the research suggests that for those who at baseline tend to cheat, markers of cognitive control (using an EEG to measure brain activity) increase when they don’t cheat and behave honestly. That’s actually not the surprising part, and fits the classic narrative that people tend to cheat unless they exert self-control to be honest. However, those who are more honest at baseline show the same markers of increased cognitive control when they do cheat. They have to override their inherent instinct in the same way that baseline cheaters do. What’s happening here?

Before I discuss how to interpret all this, let me explain the research paradigm. Subjects were tasked with finding differences between two similar images. If they could find three differences, they were given a real reward. However, some of the images only had two differences, so subjects had to either accept defeat or cheat in order to win. First subjects were tested at baseline to determine their inherent tendency to cheat. Then they were encouraged to cheat with the rigged games. EEGs were used to measure theta wave activity in specific parts of the brain, which correlates with the degree of cognitive control. Subjects who cheated more at baseline showed increased theta activity when they didn’t cheat, and those who were more honest at baseline showed increased theta activity when they cheated.

Therefore, it appears more accurate to say that cognitive control allows us not to do the morally “correct” thing, but to act against our instincts, whatever they are. But why would people have such different instincts in the first place?

I think the best way to look at this is evolutionarily (and yes, this is a bit of evolutionary psychology). A simplified schematic of the human brain is a hierarchical behavioral algorithm. Our “lizard” brains contain algorithms for basic behaviors such as eating, drinking, fight flight or freeze reactions, procreation, and self-preservation. Mammals, and especially primates, and of primates especially humans, have a neocortex that includes “executive function”. Executive function is essentially a high level tactical analysis machine that is capable of strategically considering our long-term best interests and overriding our short term more basic desires. We may gain some immediate advantage from lying, but our executive function knows it is strategically better in the long run to cultivate a reputation for being honest.

There is another layer to all this in that vertebrates (not just humans) have attached emotions to these algorithms, so that we feel that the most advantageous decision is the “right” decision. We experience this as morality, but really it’s just evolved internalized behavioral algorithms. Our sense of justice, of moral disgust, our tendency to be judgmental, all derive from these moral emotions which are meant to motivate us to behave in a strategic manner in an intensely socialized species. There are multiple behavioral emotions, however, and they often conflict. When they do, our executive function is supposed to be the judge, to resolve any conflicts. The conflicts cause cognitive dissonance, which makes us feel bad, and when we resolve the dissonance our reward centers get a shot of dopamine, and we feel good.

As with everything, these behavioral algorithms display a lot of individual variation. There is no one perfect or optimal balance, and there are different survival strategies that individuals can pursue. Some people do quite well for themselves (evolutionarily) by cheating all the time, while others do quite well cultivating a reputation for being a good and honest person. These are calculations happening mostly at a subconscious level, with our frontal lobes mostly rationalizing our decisions to reduce cognitive dissonance. But we can strategically override our default behavior in order to adapt to complex local situations. It’s part of what makes humans so adaptable.

There is yet another layer to all this, and that is culture and society. We don’t have to be slaves to our evolved cognitive tendencies. As a species we can develop things like philosophy, where we carefully think through all the consequences of different behaviors. We can do this collectively, over thousands of years, hashing out the implications of different behaviors, examining logic for internal consistency, and exploring notions of fairness and justice. All of this essentially informs our executive function, so that we can make very high level strategic decisions. Not only that, but being backed by a well thought-out philosophy increases confidence in our moral decisions and short-circuits rationalization. Society also has rules, laws, consequences, and norms of behavior that further facilitate pro-social behavior and minimize destructive selfish behavior.

No philosophy and no system is perfect, of course, but it does shift the behavioral algorithms in a direction that allows billions of people to share the same planet. Will it be enough remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, have a better neurological understanding of our own decision-making might shift our individual balance a bit in favor of executive function and also motivate us to better inform our own executive function so that we can make better decisions.