Jan 13 2015

Chimp and Human DNA

I was recently asked to respond to an apologist page that challenged the scientific claim that human and chimpanzee DNA are very similar, which is evidence that we are descended from a recent common ancestor. You have probably heard the claim that human and chimp DNA are 96% the same. The apologist was referencing the work of Jeffrey Tomkins in his “peer reviewed” study showing that there is only 70% similarity. In fact, the the DNA of chimps and humans are so different, Tomkins claims, that there would not have been enough time for evolution to account for all the changes.

I was recently asked to respond to an apologist page that challenged the scientific claim that human and chimpanzee DNA are very similar, which is evidence that we are descended from a recent common ancestor. You have probably heard the claim that human and chimp DNA are 96% the same. The apologist was referencing the work of Jeffrey Tomkins in his “peer reviewed” study showing that there is only 70% similarity. In fact, the the DNA of chimps and humans are so different, Tomkins claims, that there would not have been enough time for evolution to account for all the changes.

This is what I like to call, “sophisticated nonsense.” The very purpose of pseudoscience such as this is to confuse the public with complicated arguments that only scientists are likely to understand. We can turn such pseudoscience, however, into teachable moments.

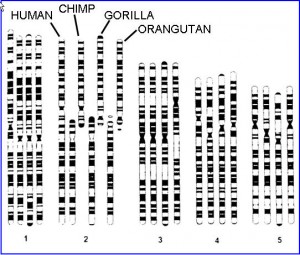

For background, it is helpful to understand that there is no completely objective way to come up with one number that represents the percent similarity between the DNA of two species. There are just too many different choices to make in terms of how to count similarity. For example, how do you count chromosomal differences? Do you just compare the sequences of genes in common? What about insertions, gene duplications, and deletions? Do you line up sequences to their best match and just count point mutations? Do you count non-coding segments?

There is no one right way to do it to give a definitive answer of similarity. However, if you have a specific question in mind, then the method you choose should be designed to answer the question.

In this case we do have a very specific question – how recent, according to a comparison of human and chimp DNA, is the most recent common ancestor likely to be? What geneticists do to answer this question is take segments that the two species have in common, line them up, and then count point mutations. They then can calculate, given known mutation rates, how long the two samples of DNA have been evolving away from each other. Each species is accumulating new mutations over time at a fairly predictable rate.

Doing this kind of analysis has yielded a variety of answer, from 8-13 million years ago. The range is due to the way in which the comparisons were made and how the mutation rates were calibrated. Also, when an ancestral population splits into two is not always a clean event. Different populations can have decreased interaction over millions of year, with occasional back breeding before the split is final. So a genetic split of 13 million years is still compatible with fossil evidence of a split 8 million years ago.

What about the percent? With this type of analysis scientists come up with a range, about 95-98% similarity between human and chimp. The average number of 96%, derived after the complete mapping of the chimp genome, is now generally accepted. But this number is just representative. It depends on what you’re looking at. Some genes are highly conserved, others less so.

So how does Tomkins come up with 70%. Well, he is not comparing point mutations of aligned segments. He is comparing chromosomes to see how many segments line up to some arbitrary amount. As many others have already pointed out, this result is not wrong, it’s just irrelevant. Well, it might also be wrong. Others have found it difficult to reproduce his results. But even if his analysis is accurate, it is simply the wrong analysis to apply to dating the last common ancestor.

To explain the problem further, he is applying mutation rates for point mutations (changing a single base pair) to other types of mutations, like gene duplications or insertions, that might change thousands or millions of base pairs with a single mutation. He is essentially treating a single mutation that results in the insertion of 10,000 base pairs into the genome as if it were 10,000 separate mutations of single base pairs.

How did he get such a blatant error past peer-review? Well, that is the reason for the scare quotes around “peer-review” above. He published in a young-earth creationist rag, Answers Research Journal. He published ideologically motivated nonsense in an ideologically motivated journal, the purpose of which is that creationists can go around citing peer-reviewed papers to befuddle non-scientists.

It works. The apologist to whom I was asked to respond was doing just that on his Facebook page, bludgeoning any commenters with his peer-reviewed source. The average Facebook commenter is not going to spend the time to do the requisite searching, coming up with half a dozen references to give proper background to the science, and specific sources addressing the Tomkins paper. Even if they tried, without a sufficient background in science it may be difficult to understand the logic behind interspecies DNA comparisons to calculate last common ancestor.

That is why it is perfectly reasonable to side with the scientific consensus, even when someone confronts you with apparently sophisticated arguments or evidence. It is also reasonable to dismiss evidence because the source is obviously ideological or does not seem reputable.

Unfortunately, those types of judgments can sometimes be complex also, and sometimes sophisticated nonsense works its way into reputable journals. There is no simple algorithm you can apply. Sometimes you just have to have a working knowledge of the science. You may also rely upon proven trustworthy sources, but then you susceptible to overreliance on authority.

The pseudoscientists have a distinct advantage here. All they have to do is muddy the waters and sow doubt and confusion.

There are some fairly reliable red flags that can help, however, and we discuss these often. Sources that are obscure, seem ideologically bound, or have direct commercial interests are suspect. Extreme minority opinions are probably in the minority for a reason. Invoking conspiracy theories to explain rejection by the mainstream scientific community is almost certainly nonsense. Invoking unseen, magical, mystical, or paranormal powers or effects is a huge red flag.

In the end, for the non-expert, it is best to use a combination of methods. Examine claims for these and other red flags. Rely upon trusted scientific sources, but also make an effort to understand the scientific basics so at least you can apply a basic smell test to claims. And of course there are now many scientists and experts on social media who would be happy to dissect such claims, so use them as a resource.

Unfortunately, well organized pseudosciences like creationism have their own experts, their own social media warriors, and now even their own peer-reviewed journals, institutions, and other trappings of legitimacy. They have been unable to gain acceptance by mainstream science through evidence or argument, and so they have simply created a bizarro world alternative in which they are correct. They no longer have to convince actual scientists, they can simply talk to each other and generate sophisticated nonsense to confuse the public.