Aug

18

2023

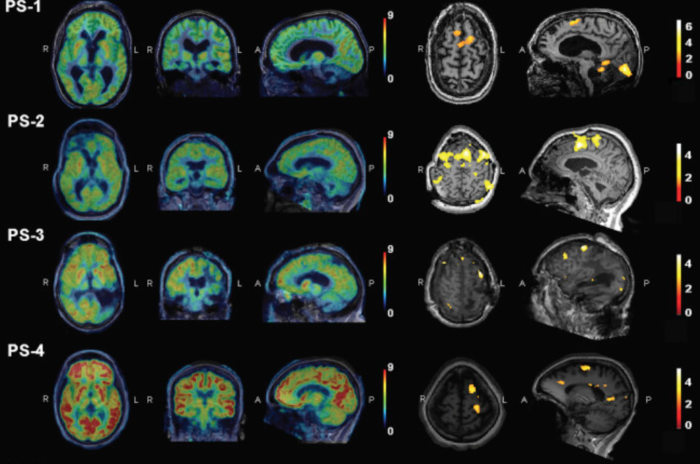

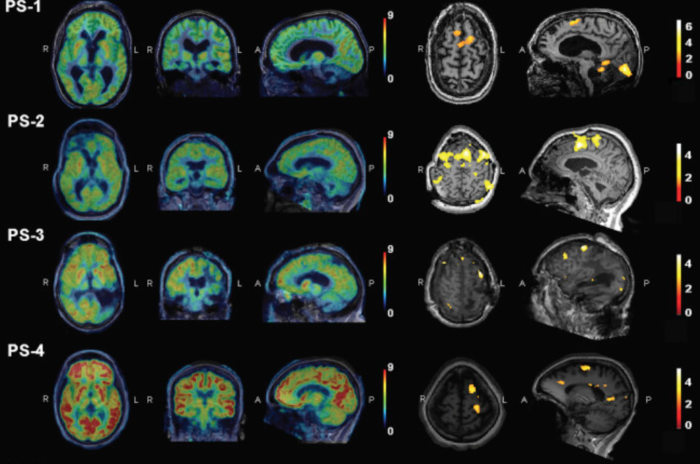

What’s going on in the minds of people who appear to be comatose? This has been an enduring neurological question from the beginning of neurology as a discipline. Recent technological advances have completely changed the game in terms of evaluating comatose patients, and now a recent study takes our understanding one step further by teasing apart how different systems in the brain contribute to conscious responsiveness.

What’s going on in the minds of people who appear to be comatose? This has been an enduring neurological question from the beginning of neurology as a discipline. Recent technological advances have completely changed the game in terms of evaluating comatose patients, and now a recent study takes our understanding one step further by teasing apart how different systems in the brain contribute to conscious responsiveness.

This has been a story I have been following closely for years, both as a practicing neurologist and science communicator. For background, when evaluating patients who have a reduced ability to execute aspects of the neurological exam, there is an important question to address in terms of interpretation – are they not able to perform a given task because of a focal deficit directly affecting that task, are they generally cognitively impaired or have decreased level of conscious awareness, or are other focal deficits getting in the way of carrying out the task? For example, if I ask a patient to raise their right arm and they don’t, is that because they have right arm weakness, because they are not awake enough to process the command, or because they are deaf? Perhaps they have a frozen shoulder, or they are just tired of being examined. We have to be careful in interpreting a failure to respond or carry out a requested action.

One way to deal with this uncertainty is to do a thorough exam. The more different types of examination you do, the better you are able to put each piece into the overall context. But this approach has its limits, especially when dealing with patients who have a severe impairment of consciousness, which gets us to the context of this latest study. For further background, there are different levels of impaired consciousness, but we are talking here about two in particular. A persistent vegetative state is defined as an impairment of consciousness in which the person has zero ability to respond to or interact with their environment. If there is any flicker of responsiveness, then we have to upgrade them to a minimally conscious state. The diagnosis of persistent vegetative state, therefore, is partly based on demonstrating the absence of a finding, which means it is only as reliable as the thoroughness with which one has looked. This is why coma specialists will often do an enhanced neurological exam, looking really closely and for a long time for any sign of responsiveness. Doing this picks up a percentage of patients who would otherwise have been diagnosed as persistent vegetative.

Continue Reading »

Aug

10

2023

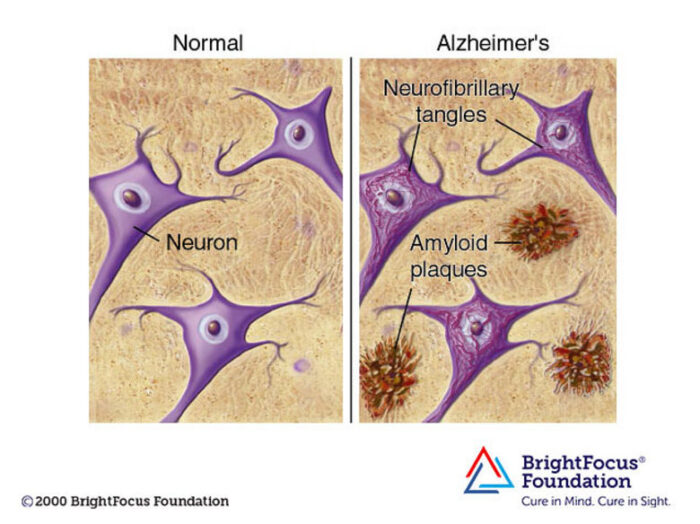

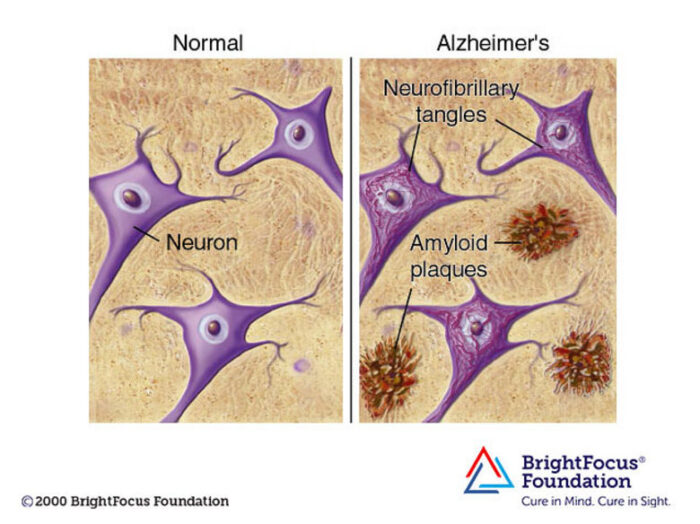

Decades of complex research and persevering through repeated disappointment appears to be finally paying off for the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In 2021 Aduhelm was the first drug approved by the FDA (granted contingent accelerated approval) that is potentially disease-modifying in AD. This year two additional drugs received FDA approval. All three drugs are monoclonal antibodies that target amyloid protein. They each seem to have overall modest clinical effect, but they are the first drugs to actually slow down progression of AD, which represents important confirmation of the amyloid hypothesis. Until now attempts at slowing down the disease by targeting amyloid have failed.

Decades of complex research and persevering through repeated disappointment appears to be finally paying off for the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In 2021 Aduhelm was the first drug approved by the FDA (granted contingent accelerated approval) that is potentially disease-modifying in AD. This year two additional drugs received FDA approval. All three drugs are monoclonal antibodies that target amyloid protein. They each seem to have overall modest clinical effect, but they are the first drugs to actually slow down progression of AD, which represents important confirmation of the amyloid hypothesis. Until now attempts at slowing down the disease by targeting amyloid have failed.

Three drugs in as many years is no coincidence – this is the result of decades of research into a very complex disease, combined with monoclonal antibody technology coming into its own as a therapeutic option. AD is a form of dementia, a chronic degenerative disease of the brain that causes the slow loss of cognitive function and memory over years. There are over 6 million people in the US alone with AD, and it represents a massive health care burden. More than 10% of the population over 65 have AD.

The probable reason we have rapidly crossed over the threshold to detectable clinical effect is attributed by experts to two main factors – treating people earlier in the disease, and giving a more aggressive treatment (essentially pushing dosing to a higher level). The higher dosing comes with a downside of significant side effects, including brain swelling and bleeding. But that it what it took to show even a modest clinical benefit. But the fact that three drugs, which target different aspects of amyloid protein, show promising or demonstrated clinical benefit helps confirm that the amyloid protein and the plaques they form in the brain are, to some extend driving AD. They are not just a marker for brain cell damage, they are at least partly responsible for that damage. Until now, this was not clear.

Continue Reading »

Jul

18

2023

Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts.

Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts.

Knowing facts is still important, because you cannot think in a vacuum. Our internal model of the world is build on bricks of fact, but before we take a brick and place it in our wall of knowledge, we have to decide if it is probably true or not. I have come to think about this in terms of three categories of skills – domain knowledge (with scientific claims this is scientific literacy), critical thinking, and media savvy.

Domain knowledge, or scientific literacy, is important because without a working knowledge of a topic you have no basis for assessing the plausibility of a new claim. Does it even make basic sense? An easily refutable claim may be accepted simply because you don’t know it is easily refutable. Critical thinking skills involve an understanding of the heuristics we naturally use to estimate truth, our cognitive biases, cognitive pitfalls like conspiracy thinking, how motivation affects our thought processes, and mechanisms of self deception. Media savvy involves understanding how to assess the reliability of information sources, how information ecosystems work, and how information is used by others to deceive us.

A recent study involves one aspect of this latter category – how do we assess the reliability of information sources and how this affects our bottom line assessment of whether or not something is true. The researchers did two studies involving 1,181 subjects. They gave the subjects factual information, then presented them with claims made by a media outlet. They were further told whether the media outlet intended to inform or deceive on this topic. They studies claims that are considered highly politicized and those that were not.

What they found is that subjects were more likely to deem a claim true if it came from a source considered to be trying to inform, and more likely to be false when the source was characterized as trying to deceive – even if the claims were the same. At first this result seems strange because the subjects were told the actual facts, so they knew absolutely (within the confines of the study) whether or not the claim was true.

Continue Reading »

Jun

19

2023

In my last post I noted that even mentioning general vague support for the LGBTQ community was enough to trigger very specific feedback, often making erroneous scientific claims. Each claim requires a deep dive and article-length discussion. Even though the discussion that followed in the comments was better than I thought it would be, it still filled with additional dubious claims. I suspect there are two main reasons for this. The first is that the topic of gender identity is complex and not intuitive. It may feel intuitive, as if your immediate gut reaction is all that is necessary to deal adequately with the topic, but it really isn’t. Ultimate this topic deals with how our brains construct our own sense of self, identity, and reality. These are always tricky concepts to deal with – and as I have pointed out before in other contexts, our brain constructs are counterintuitive by their very nature. In other words, our brains evolved for these constructs to feel real and automatic, and for the subconscious processes that create them to be invisible to us.

Second, the issue of gender identity has been highly politicized. This has resulted in any discussion of the topic being flooded with biased and deliberate misinformation. The usual FUD (fear, uncertainty doubt) strategies apply. And of course – science is hard. Even seemingly straightforward questions are actually quite complex. This makes it easy to create confusion by “just asking questions” or selectively applying skepticism.

One question at the heart of the trans issue is this – what is the rate of regret or even detransitioning after medical transition? One narrative is that adolescents (often conflated with “children”) are being prematurely herded down a road to transition, which they later regret. The other narrative is that, generally speaking, making the decision to transition is taken very seriously, with very low levels of later regret. Which is true?

Continue Reading »

Jun

16

2023

On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”

On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”

Being trans itself is not considered a mental illness, but this deserves some extensive discussion. It’s important to first establish some basic principles, starting with – what is mental illness? This is a deceptively tricky question. The American Psychiatric Association provides this definition:

Mental illnesses are health conditions involving changes in emotion, thinking or behavior (or a combination of these). Mental illnesses can be associated with distress and/or problems functioning in social, work or family activities.

But this is not a technical or operational definition (something that requires book-length exploration to be thorough), but rather a quick summary for lay readers. In fact, there is no one generally accepted technical definition. There is some heterogeneity throughout the scientific literature, and it may vary from one illness to another and one institution to another. But there are some generally accepted key elements.

First, as the WHO states, “Mental disorders involve significant disturbances in thinking, emotional regulation, or behaviour.” But then we have to define “disorder”, which is typically defined as a lack or alternation in a function possessed by most healthy individuals that causes demonstrable harm. “Significant” is also a word that’s doing a lot of heavy lifting there. This is typically determined disorder by disorder, but usually includes elements of persistent duration for greater than some threshold, and some pragmatic measure of severity. For example, does the disorder prevent someone from participating in meaningful activity, productive work, or activities of daily living? Does it provoke other demonstrable harms, such as severe depression or anxiety? Does it entail increased risk of negative health or life outcomes?

Continue Reading »

Jun

13

2023

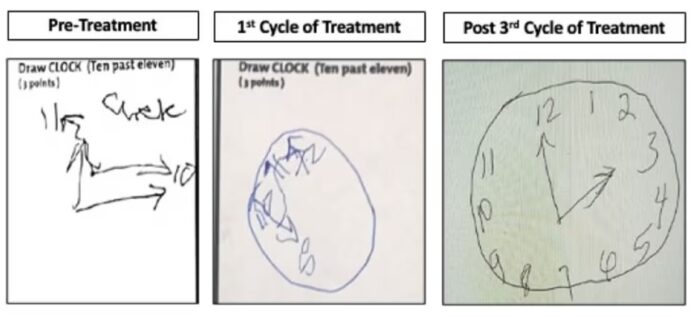

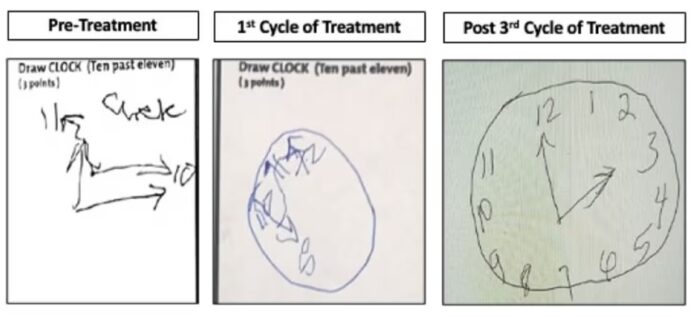

The story of a woman, in a severe state of catatonia for years and “waking up” after being treated for an autoimmune disease, is making the rounds and deserves a little bit of context. April Burrell was diagnosed with a severe form of schizophrenia resulting in catatonia, and has been in long term care since 2000. However, she was also more recently found to have lupus, an autoimmune disease that can affect the brain. After being treated with immunosuppressive medications, multiple courses of treatment over months, her condition steadily improved. She still has symptoms of psychosis and is not cognitively normal, but is able to recognize people and interact and does much better on standard cognitive tests. The credit for her recovery goes to a psychiatrist, Sander Markx, who had seen the patient 20 years before, and upon learning that she was still institutionalized and unchanged order the workup that resulted in the diagnosis.

The story of a woman, in a severe state of catatonia for years and “waking up” after being treated for an autoimmune disease, is making the rounds and deserves a little bit of context. April Burrell was diagnosed with a severe form of schizophrenia resulting in catatonia, and has been in long term care since 2000. However, she was also more recently found to have lupus, an autoimmune disease that can affect the brain. After being treated with immunosuppressive medications, multiple courses of treatment over months, her condition steadily improved. She still has symptoms of psychosis and is not cognitively normal, but is able to recognize people and interact and does much better on standard cognitive tests. The credit for her recovery goes to a psychiatrist, Sander Markx, who had seen the patient 20 years before, and upon learning that she was still institutionalized and unchanged order the workup that resulted in the diagnosis.

This is a remarkable case, but is not ultimately surprising. I had a similar case as a resident. A patient was admitted with worsening schizophrenia. He had severe schizophrenia for the last 20 years or so, mostly cared for at home by his family, but now was simply getting too difficult to give proper care. He was admitted to the psychiatry floor, and they consulted the neurology service almost as an afterthought, because the patient had been lost to follow up for so long. We had a low clinical suspicion that there was anything neurological going on, but recommended a CT scan of the brain and other workup, just to be thorough. The CT scan found a very large tumor pushing in on his frontal lobes. The tumor itself was outside the brain but inside the skull. Neurosurgery was consulted, the tumor was promptly removed, and within days the patient was almost back to his pre-schizophrenic baseline – essentially cured. That’s the kind of case you never forget.

To put such cases into clinical perspective it’s important to recognize that schizophrenia is a clinical diagnosis, meaning that it is based upon signs and symptoms, not any pathological findings on imaging or laboratory workup. There are markers and researchers are trying to understand it better as a brain disease, but for now the diagnosis is still mainly clinical. Part of the clinical diagnosis, however, is ruling out neurological pathology. This is a standard referral that we neurologists get from psychiatrists – rule out neurological disease. Only when that is done is the patient given a psychiatric diagnosis.

Continue Reading »

May

02

2023

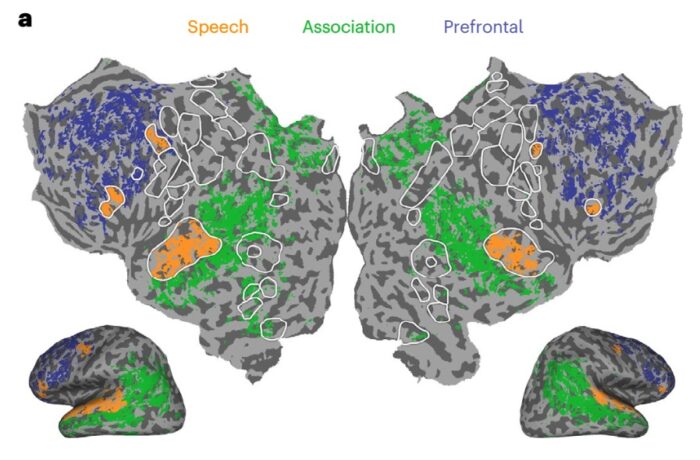

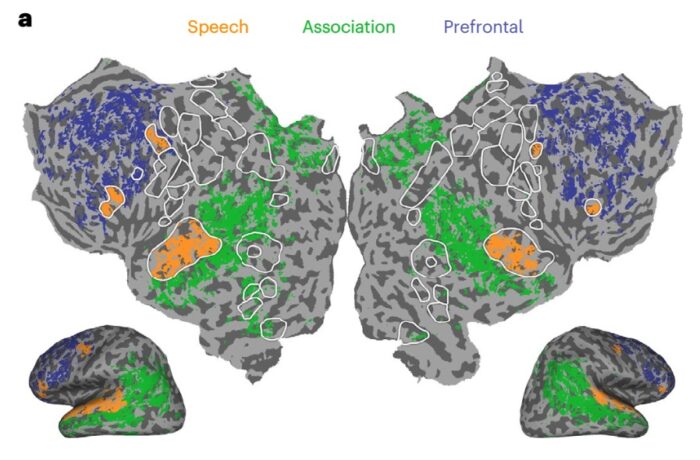

This is pretty exciting neuroscience news – Semantic reconstruction of continuous language from non-invasive brain recordings. What this means is that researchers have been able to, sort of, decode the words that subjects were thinking of simply by reading their fMRI scan. They were able to accomplish this feat using a large language model AI, specifically GPT-1, an early version of Chat-GPT. It’s a great example of how these AI systems can be leveraged to aid research.

This is pretty exciting neuroscience news – Semantic reconstruction of continuous language from non-invasive brain recordings. What this means is that researchers have been able to, sort of, decode the words that subjects were thinking of simply by reading their fMRI scan. They were able to accomplish this feat using a large language model AI, specifically GPT-1, an early version of Chat-GPT. It’s a great example of how these AI systems can be leveraged to aid research.

This is the latest advance in an overall research goal of figuring out how to read brain activity and translate that activity into actual thoughts. Researchers started by picking some low-hanging fruit – determining what image a person was looking at by reading the pattern of activity in their visual cortex. This is relatively easy because the visual cortex actually maps to physical space, so if someone is looking at a giant letter E, that pattern of activity will appear in the cortex as well.

Moving to language has been tricky, because there is no physical mapping going on, just conceptual mapping. Efforts so far have relied upon high resolution EEG data from implanted electrodes. This research has also focused on single words or phrases, and often trying to pick one from among several known targets. This latest research represents three significant advances. The first is using a non-invasive technique to get the data, fMRI scan. The second is inferring full sentences and ideas, not just words. And the third is that the targets were open-ended, not picked from a limited set of choices. But let’s dig into some details, which are important.

Continue Reading »

Apr

28

2023

The show Ted Lasso is about to wrap up its final season. I am one of the many people who really enjoy the show, which turns on a group of likable people helping each other through various life challenges with care and empathy. Lasso is an American college football coach who was recruited to coach an English “football” team, and manages to muddle through with Zen-like calm and folksy good spirits.

The show Ted Lasso is about to wrap up its final season. I am one of the many people who really enjoy the show, which turns on a group of likable people helping each other through various life challenges with care and empathy. Lasso is an American college football coach who was recruited to coach an English “football” team, and manages to muddle through with Zen-like calm and folksy good spirits.

Although entertaining, is the Ted Lasso style of coaching effective? Is it more effective to coach more like a drill sergeant, with fear and intimidation? It’s interesting that the fear-based model of leadership, whether coaching or otherwise, seems to be intuitive. It’s the default mode for many people. But evidence increasingly shows that the Ted Lasso model works better. Empathy may be the most effective leadership style.

Coaches who lead with empathy tend to get more out of their athletes, foster loyalty, establish trust and more effective communication. When you think about it, it makes sense. People work harder when they are motivated. Fear-based motivation is ultimately external, the fear of displeasing a leader, earning their wrath or punishment. Empathy nurtures internal motivation, wanting to succeed because you feel confident, and you want to achieve personal and group goals.

This philosophy is not new – this is a form of the old cliche of catching more flies with honey than vinegar. The philosophy has also filtered into the education community, which increasingly emphasizes positive reward rather than negative feedback. Making students feel anxious or stupid, it turns out, is counterproductive. This can be taken too far as well, however. I have seen it manifest as a policy of never telling students they are wrong. But what if they are? Well, don’t ask them a question that can be right or wrong, therefore there is no possibility of being wrong. OK, but some answers are still better than others.

Continue Reading »

Apr

13

2023

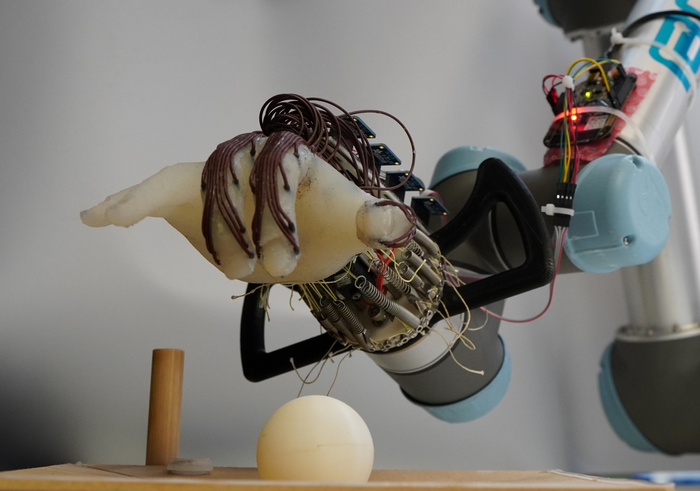

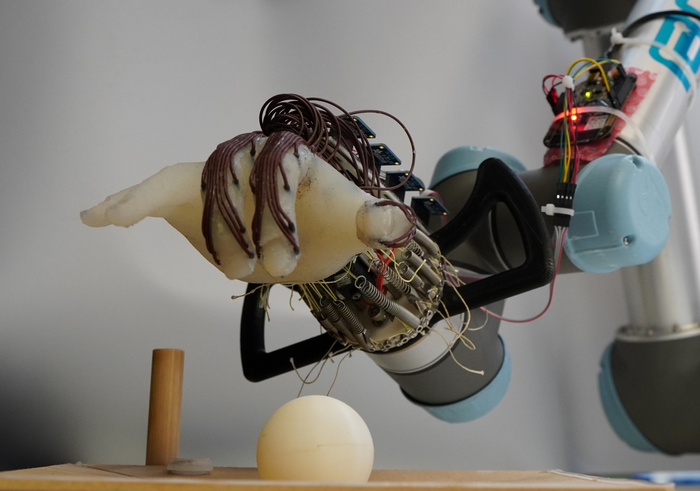

Roboticists are often engaged in a process of reinventing the wheel – duplicating the function of biological bodies in rubber, metal, and plastic. This is a difficult task because biological organisms are often wondrous machines. The human hand, in particular, is a feat of evolutionary engineering.

Roboticists are often engaged in a process of reinventing the wheel – duplicating the function of biological bodies in rubber, metal, and plastic. This is a difficult task because biological organisms are often wondrous machines. The human hand, in particular, is a feat of evolutionary engineering.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have designed a robotic hand that both reflects the challenge of this task and some of the principles that might help guide the development of this technology. One feature of this study struck me as significant because of how it reflects the actual function of the human hand, in a way not mentioned in the paper or press release. This made me wonder if the roboticists were even aware that they were replicating a known principle.

The phenomenon in question is called tenodesis (I did a search on the paper and could not find this term). I learned about this during my neurology residency when rotating in a rehab hospital. When you extend your wrist this pulls the tendons of the fingers tight and causes the fingers to flex into a weak grasp. For people with a spinal cord injury around the C6-7 level, they can extend their wrist but not grasp their fingers. So they can learn to exploit the tenodesis effect to have a functional grasp, which can make a huge difference to their independence.

The Cambridge roboticists have apparently independently hit upon this same idea. They designed a robot hand that is anthropomorphic but where the fingers were not attached to actuators. The robot, however, could flex its wrist, which would passively cause the fingers to flex into a grasp – exactly as it happens in human hands with tenodesis. But why would roboticists want to make a robot hand with “paralyzed” fingers? The answer is – to optimize efficiency. Attaching all the fingers to actuators is a complex engineering feat and also using those actuators consumes a lot of energy. Passive grip is therefore much more energy efficient, which is a huge advantage in robotics.

Continue Reading »

Apr

03

2023

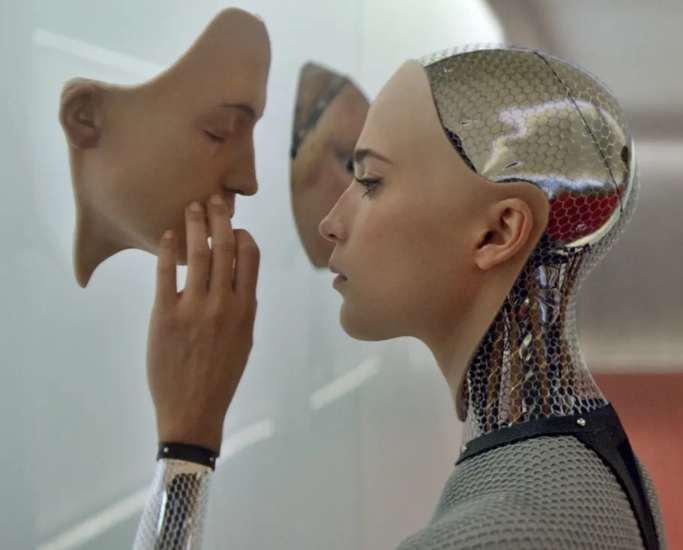

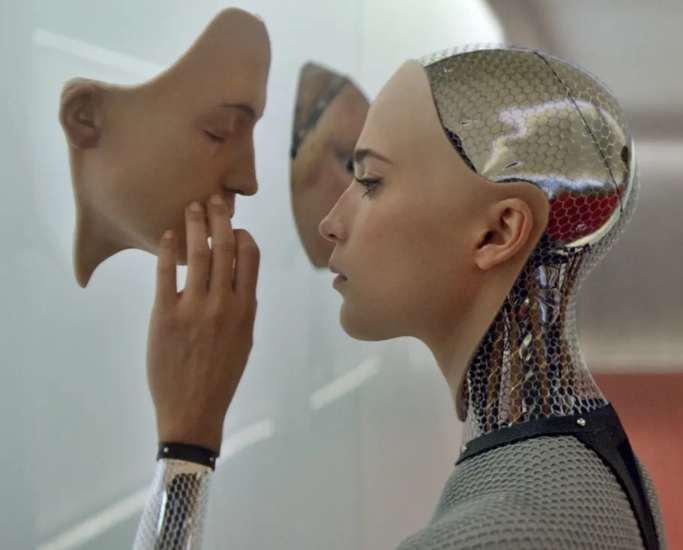

On the SGU this week we interviewed Blake Lemoine, the ex-Google employee who believes that Google’s LaMDA may be sentient, based on his interactions with it. This was a fascinating discussion, and even though I think we did a pretty deep dive in the time we had, it also felt like we were just scratching the surface of the complex topic. I want to summarize the topic here, give the reasons I don’t agree with Blake, and add some further analysis.

On the SGU this week we interviewed Blake Lemoine, the ex-Google employee who believes that Google’s LaMDA may be sentient, based on his interactions with it. This was a fascinating discussion, and even though I think we did a pretty deep dive in the time we had, it also felt like we were just scratching the surface of the complex topic. I want to summarize the topic here, give the reasons I don’t agree with Blake, and add some further analysis.

First, let’s define some terms. Intelligence is essentially the ability to know and process information, often in the context of adapting one’s responses to that information. A calculator, therefore, displays a type of intelligence. Sapience is deeper, implying understanding, perspective, insight, and wisdom. Sentience is the subjective experience of one’s existence, the ability to feel. And consciousness is the ability to be awake, to receive and process input and generate output, and to have some level of control over that process. Consciousness implies spontaneous internal mental activity, not just reactive.

These concepts are a bit fuzzy, they overlap and interact with each other, and we don’t really understand them fully phenomenologically, which is part of the problem of talking about whether or not something is sentient. But that doesn’t mean that they are meaningless concepts. There is clearly something going on in a human brain that is not going on in a calculator. Even if we consider a supercomputer with the processing power of a human brain, able to run complex simulations and other applications – I don’t think there is a serious argument to be made that it is sentient. It is not experiencing its own existence. It does not have feelings or emotions.

The question at hand is this – how do we know if something that displays intelligent behavior also is sentient? The problem is that sentience, by definition, is a subject experience. I know that I am sentient because of my own experience. But how do I know that any other living human being is also sentient?

Continue Reading »

What’s going on in the minds of people who appear to be comatose? This has been an enduring neurological question from the beginning of neurology as a discipline. Recent technological advances have completely changed the game in terms of evaluating comatose patients, and now a recent study takes our understanding one step further by teasing apart how different systems in the brain contribute to conscious responsiveness.

What’s going on in the minds of people who appear to be comatose? This has been an enduring neurological question from the beginning of neurology as a discipline. Recent technological advances have completely changed the game in terms of evaluating comatose patients, and now a recent study takes our understanding one step further by teasing apart how different systems in the brain contribute to conscious responsiveness.

Decades of complex research and persevering through repeated disappointment appears to be finally paying off for the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In 2021 Aduhelm was the first drug approved by the FDA (granted contingent accelerated approval) that is potentially disease-modifying in AD. This year

Decades of complex research and persevering through repeated disappointment appears to be finally paying off for the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In 2021 Aduhelm was the first drug approved by the FDA (granted contingent accelerated approval) that is potentially disease-modifying in AD. This year Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts.

Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts. On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”

On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.” The

The  This is pretty exciting neuroscience news –

This is pretty exciting neuroscience news – The show Ted Lasso is about to wrap up its final season. I am one of the many people who really enjoy the show, which turns on a group of likable people helping each other through various life challenges with care and empathy. Lasso is an American college football coach who was recruited to coach an English “football” team, and manages to muddle through with Zen-like calm and folksy good spirits.

The show Ted Lasso is about to wrap up its final season. I am one of the many people who really enjoy the show, which turns on a group of likable people helping each other through various life challenges with care and empathy. Lasso is an American college football coach who was recruited to coach an English “football” team, and manages to muddle through with Zen-like calm and folksy good spirits. Roboticists are often engaged in a process of reinventing the wheel – duplicating the function of biological bodies in rubber, metal, and plastic. This is a difficult task because biological organisms are often wondrous machines. The human hand, in particular, is a feat of evolutionary engineering.

Roboticists are often engaged in a process of reinventing the wheel – duplicating the function of biological bodies in rubber, metal, and plastic. This is a difficult task because biological organisms are often wondrous machines. The human hand, in particular, is a feat of evolutionary engineering. On

On