Feb 11 2019

Caring About Robots

Would you sacrifice a human to save a robot? Psychologists have set out to answer that question using the classic trolley problem.

Would you sacrifice a human to save a robot? Psychologists have set out to answer that question using the classic trolley problem.

Most people by now have probably heard about the trolley dilemma, as it has seeped into popular culture. This is a paradigm of psychology research in which subjects are presented with a dilemma – a trolley is racing down the tracks and the breaks have failed. It is heading toward 5 people who are unaware they are about to be killed. You happen to be right next to the lever that can switch the trolley to a different track, where there is only one person at risk. Would you switch the tracks to save the 5 people, but condemning the 1 person to death? Most people say yes. What if in the same situation you were on the trolley at the front of the car, and in front of you was a particularly large person – large enough that if you pushed them off the front of the trolley their bulk would stop the car and save the 5 people, but surely kill the person you pushed over (I know, this is contrived, but just go with it). Would you do it? Far fewer people indicate that they would.

The basic setup is meant to test the difference between being a passive vs active cause of harm to others in the context of human moral reasoning. We tend not to be strictly utilitarian in our moral reasoning, thinking only of outcomes (1 death vs 5), but are emotionally concerned with whether we are the direct active cause of harm to others vs allowing harm to come through inaction or as a side consequence of our actions. The more directly involved we are, the more it bothers us, not just the ultimate outcome.

The trolley problem has become so famous because you can use it as a basic framework and then change all sorts of variables to see how it affects typical human moral reasoning. You can play with the numbers, to see if there is a threshold (how many lives must be saved in order to make a sacrifice worth it?), or you can vary the age of those saved vs those sacrificed, or perhaps the person you might sacrifice is a coworker. Does that make their life more valuable? What if they are kind of a jerk?

Essentially researchers are trying to reverse engineer the human moral algorithm – at least the emotional one. We engage in moral reasoning on two levels, an analytical one (thinking slow) and an intuitive one (thinking fast). The intuitive level is essentially how we feel – our gut reaction. Of course these two processes are not cleanly separated. We tend to rationalize with analytical thinking what we feel emotionally. We follow our gut and then justify it to ourselves later. There is often enough complexity to any situation that you can focus on whatever principles and facts are convenient to build a case to support your immediate intuitive reaction.

Of course if you have a thoughtfully constructed ethical philosophy in place ahead of time, the analytical approach can take over. Even if this is your goal, understanding the emotional algorithm is important, because it will color your analytical thinking. Also, you might argue that ethical emotions are important and part of the calculus. Making someone do something that is emotionally damaging might not be the right thing, even if it is utilitarian.

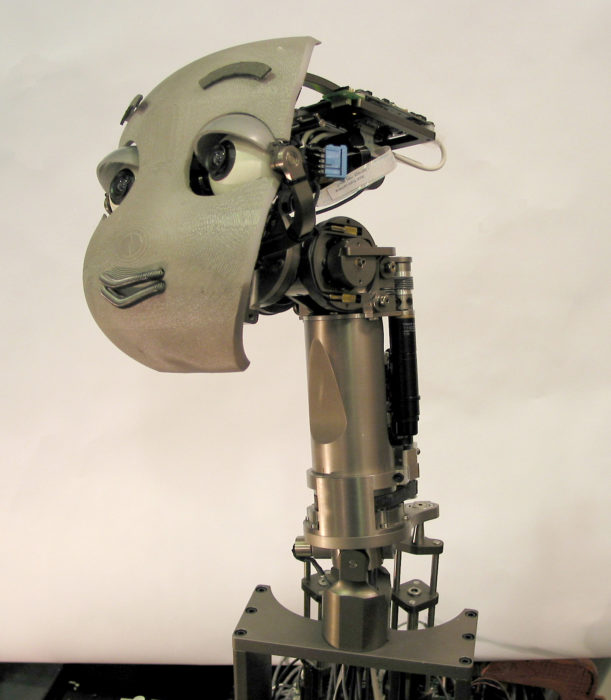

Let’s get back to the opening question – if we apply some version of the trolley dilemma to robots, how does that affect the outcome? Nijssen and her team did two experiments to test this question. In the first study the individual to be sacrificed was either a robot-looking robot, a human-looking robot, or a human. Further, the robots were described to the subjects with either a neutral priming story or one that demonstrated human attributes.

In this study the subjects were more likely to sacrifice robots than humans, but not completely. Meaning some subjects would not sacrifice a robot to save people, and were less likely to sacrifice human-looking robots. Statistically they were more likely to sacrifice robots than people, however. Further, robots described as having human characteristic were treated more like people, and less likely to be sacrificed.

The second study repeated this test but further tried to tease apart what aspects of the priming story had the larger effect, specifically telling a story in which the robot is seen to have agency (the ability to act on its own initiative) or affective states – feelings. What they found is that attributing affective states to the robots had a larger effect on treating them like people than attributing agency. So in other words, if you are faced with a cute anthropomorphic robot making those cartoon sad eyes at you, you are less likely to sacrifice it than a machine-looking robot acting with clear agency, but not mimicking human emotion.

I would say this makes sense, but if the result were the opposite I could probably make sense out of that also. We react to both the perception of agency and emotional cues so this study could have gone either way. What it suggests is that, with regard to moral reasoning, and specifically our willingness to make a sacrifice for a utilitarian outcome, emotional cues have a stronger effect.

This is important to understand on a number of levels. First, it’s always important to remember that humans generally are predictable and easy to manipulate (at least statistically). There are, in fact, entire industries dedicated to manipulating people’s emotional reactions (such as advertising and politics). Being familiar with your own pre-wired emotional algorithms is a potential hedge against being manipulated yourself.

Second, we should generally be able to make rational ethical decisions based on valid philosophical principles. Otherwise we are just following our evolved programming, which may not have been optimized for our current situation.

Finally, the authors point out that this information might inform our design of robots. This and many other studies consistently show that people will respond to and treat robots as humans if they have sufficient human-like traits. This may facilitate interactions with robots, making human users feel more comfortable. But there is a potential downside if we overplay this hand. In some situations, if we make robots seem too human (by how they look or behave) this may adversely affect decision-making about the relative value of humans and robots. Sometimes we need to sacrifice robots, or send them into dangerous situations, in order to save people or protect other more valuable assets. Painting a cute face on your bomb-retrieving robot may not be a good idea.

This problem will get more difficult as our AI behavior algorithms get more sophisticated. Some researchers are specifically creating emotion-simulating algorithms. We are heading toward creating robots that are well over the line of making most people feel as if the robots are “people” but are lacking in any real consciousness (without getting into the thorny issue of how to define or measure that).

This is one thing I think science fiction writers have generally gotten wrong. There are many visions of the future in which robots are conscious but are treated like mere machines (leading to the inevitable robot uprising). This and other research suggests the exact opposite is likely to be the case – we will treat machines like people because they are tricking our emotion-based ethical algorithms.