Oct

26

2009

A recent study, as reported in the New Scientist, purports to catch the placebo effect in the act using functional MRI scanning. This is an interesting study, and does for the first time show a neurophysiological correlate to reported placebo decreases in pain reporting.

However, reporting of the study highlights, yet again, widespread misconceptions about the nature of placebo effects – specifically that there are many placebo effects, not one placebo effect. Any reference to “the” placebo effect is therefore misleading – it is a convenient short hand, but unfortunate given prevailing misconceptions.

What most people mean when they say “the” placebo effect is a real physiological effect that derives from belief in the effects of a treatment – a mind-over-matter effect. However, the placebo effect, as it is measured in clinical trials, has a very specific operational definition. It is any and all measured effects other than a physiological response to the treatment itself.

Continue Reading »

Oct

24

2007

It is now a common belief that a positive mood leads to better health outcomes, even (or especially) when dealing with a serious illness like cancer. Like many common beliefs, this is probably not true. (The selection process of beliefs tends to favor things we would like to be true, and not necessarily things that actually are true.) Many people have championed the efficacy of a positive mood in healing, notably Dr. Bernie Seigel, who wrote the books Love, Medicine & Miracles and Peace, Love & Healing, in which he claims:

A vigorous immune system can overcome cancer if it is not interfered with, and emotional growth toward greater self-acceptance and fulfillment helps keep the immune system strong.

But such claims are the product mostly of sloppy thinking and are not backed by the evidence. In a new large well controlled study, researchers found no benefit of positive mood in cancer survival. Study author James Coyne said of his study:

We anticipated finding that emotional well-being would predict the outcome of cancer. We exhaustively looked for it, and we concluded there is no effect for emotional well-being on cancer outcome. I think [cancer survival] is basically biological. Cancer patients shouldn’t blame themselves — too often we think if cancer were beatable, you should beat it. You can’t control your cancer. For some, this news may lead to some level of acceptance.

Continue Reading »

Feb

09

2007

In response to my chiropractic entry there was a response essentially commenting that if it provides a placebo effect and people feel better, what’s the big deal. My prior entry on the placebo effect is a good place to start, but I will add a few more observations.

Although a placebo effect is of limited use, and not sufficient to justify anti-scientific treatments, let alone deception and fraud, it can also have negative consequences, and should not be viewed as benign. The primary malignant effect is that a placebo effect can seem very compelling evidence that a treatment works – meaning that it has a physiological effect. This can lead to the false conclusion that the theory behind a modality is valid, and therefore all of the claims for that modality are valid, or at least should be taken seriously.

Continue Reading »

Aug

03

2018

There is a strong scientific consensus that vaccines generally are an effective approach to preventing infectious illness. The vaccine schedule is arguably the most effective and cost effective health promotion intervention ever devised. Vaccines are a public health home-run.

There is a strong scientific consensus that vaccines generally are an effective approach to preventing infectious illness. The vaccine schedule is arguably the most effective and cost effective health promotion intervention ever devised. Vaccines are a public health home-run.

How, then, to explain the anti-vaccine movement? The anti-vaccine movement is based mainly on science-denial and conspiracy theories. This means they spread a lot of misinformation – the bits of misinformation become articles of faith, and any evidence to the contrary is denied or dismissed.

I recently received the following question, which is framed as a sincere question, but I have my suspicions that it may not be:

Have just read your article.

I fully agree that herbal medicines/substances should have full clinical trials but can never find anyone able to refer me to

any clinical trials placebo versus substance to be tested on vaccines.

So wondered if you could help me as you are obviously a man of science.

Would be very grateful as there must have been clinical trials sometime.

Even my Dr draws a blank.

Many thanks

Pam

Pam may simply be the victim of anti-vaccine propaganda, and may simply lack all Google skills, but the phrasing strongly suggests an anti-vaxxer goading a skeptic with a “gotcha” question. Since this is a common anti-vaccine trope, let me dispel it once again.

Continue Reading »

Oct

18

2016

It’s always more complicated than you think. If there is one overall lesson I learned after 20 years as a science communicator, that is it. There is a general bias toward oversimplification, which to some extent is an adaptive behavior. The universe is massive and complicated, and it would be a fool’s errand to try to understand every aspect of it down to the tiniest level of detail. We tend to understand the world through distilled narratives, simple stories that approximate reality (whether we know it or not or whether we intend to or not).

Those distilled narratives can be very useful, as long as you understand they are simplified approximations and don’t confuse them with a full and complete description of reality. Different levels of expertise can partly be defined as the complexity of the models of reality that you use. It is also interesting to think about what is the optimal level of complexity for your own purposes. I try to take a deliberate practical approach – how much complexity do I need to know?

The Hawthorne Effect

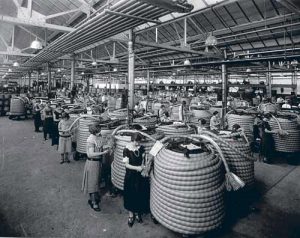

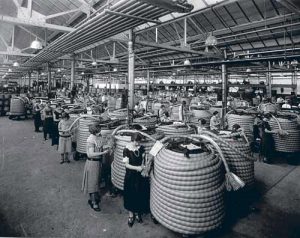

The distilled narrative of what is the Hawthorne Effect is this – the act of observing people’s behavior changes that behavior. The name derives from experiments conducted between 1924 and 1933 in Western Electric’s factory at Hawthorne, a suburb of Chicago. The experimenters made various changes to the working environment, like changing light levels, and noticed that regardless of the change, performance increased. If they increased light levels, performance increased. If they decreased light levels, performance increased. They eventually concluded that observing the workers was leading to the performance increase, and the actual change in working conditions was irrelevant. This is now referred to as an observer effect, but also the term Hawthorn Effect was coined in 1953 by psychologist J.R.P. French.

Continue Reading »

Mar

28

2013

A recently published survey at PLOS One of UK primary care doctors reports that 97% have prescribed an “impure placebo” at least once in their career. Most news reporting of this survey leave off the “impure” bit.

Let’s take a closer look at what this means.

The survey asked about “pure” placebos, which are inactive sugar pills or a similar inactive treatment, and “impure” placebos, which are effective medicines given in a way that might not have a clinical effect. The survey found that only 12% have ever prescribed a pure placebo, and only 1% do it on a regular basis. However, 97% have prescribed impure placebo ever, and 77% on a regular basis.

The survey had a 48% response rate, which is not bad for a survey, but this is why surveys are not considered strictly scientific. The low response rate introduces the potential for systematic bias – perhaps people who choose to respond do so because of a certain attitude or belief that biases their responses.

Continue Reading »

Feb

02

2012

This is yet another installment in my series on how so-called “alternative” medicine thrives under a double standard – a bizarro world where the rules of science and logic are suspended in favor of uncritical promotion. The American Headache Society (AHS) just sent out a press release endorsing acupuncture for migraine headaches. They write:

Mt. Royal, NJ (February 1, 2012) – When it comes to treating migraine, so-called “sham” acupuncture (where needles are inserted only to a superficial depth in the skin and not in specific sites) and traditional acupuncture where needles are inserted in specific sites, both are effective, according to the American Headache Society (AHS).

Citing publicity surrounding a recent Canadian study comparing the effectiveness of the two types of acupuncture, David W. Dodick, MD, AHS president, said both types of acupuncture, particularly when electrical stimulation is involved, may work to release endorphins that are important in controlling signals of pain and inflammation.

“How much of a benefit sham acupuncture can have on the release of these chemicals is unclear,” he said. “This suggests the benefits of treatment may not depend on the exact technique of acupuncture and needle positioning.”

Studies show that sham acupuncture is as effective as true acupuncture, and Dr. Dodick concludes from this that both work. The proper scientific interpretation of this result is that the treatment (acupuncture) is no different than placebo (sham acupuncture) and therefore has only a placebo effect. Only in CAM world can you take a negative result and then spin it into a positive result like this. Science is all about controlling for variables, and when you control for the variable of acupuncture (inserting needles into acupuncture points) it does not work.

Continue Reading »

Jul

19

2011

I am just getting back from The Amazing Meeting (TAM9 from Outer Space) – it was awesome but I had no time to blog while there. One of the events I participated in at TAM was a panel discussion on placebo medicine. We decided to focus on placebos for our science-based medicine panel because it increasingly looks like this will be the front lines for the next phase of the battle against pseudoscience in medicine.

I began the panel discussion by declaring victory, of a sorts. Over the last two decades the public and the scientific community have be told by CAM (complementary and alternative medicine) proponents that we were missing out on many potentially very useful and effective medical treatments simply because they are from other cultures or do not fit into the current scientific paradigm. “Give us the resources to research these diamonds in the rough,” they argued, “and we will give you new tools to promote health.”

Well – a couple a decades and a few billions of dollars worth of research later, and the CAM community has essentially nothing to show for it. The research is in: none of the major CAM modalities actually work. The evidence shows that homeopathy is just water, that acupuncture is no more effective than the kind attention of the practitioner, and that mystical life energies in fact do not exist.

Continue Reading »

Dec

13

2010

While there is a complex spectrum of attitudes toward science, there are three clusters worth pointing out, specifically in reference to the provocative New Yorker article by Jonah Lehrer called The Truth Wears Off. The first group are those with an overly simplistic or naive sense of how science functions. This is a view of science similar to those films created in the 1950s and meant to be watched by students, with the jaunty music playing in the background. This view generally respects science, but has a significant underappreciation for the flaws and complexity of science as a human endeavor. Those with this view are easily scandalized by revelations of the messiness of science.

The second cluster is what I would call scientific skepticism – which combines a respect for science and empiricism as a method (really “the” method) for understanding the natural world, with a deep appreciation for all the myriad ways in which the endeavor of science can go wrong. Scientific skeptics, in fact, seek to formally understand the process of science as a human endeavor with all its flaws. It is therefore often skeptics pointing out phenomena such as publication bias, the placebo effect, the need for rigorous controls and blinding, and the many vagaries of statistical analysis. But at the end of the day, as complex and messy the process of science is, a reliable picture of reality is slowly ground out.

The third group, often frustrating to scientific skeptics, are the science-deniers (for lack of a better term). They may take a postmodernist approach to science – science is just one narrative with no special relationship to the truth. Whatever you call it, what the science-deniers in essence do is describe all of the features of science that the skeptics do (sometimes annoyingly pretending that they are pointing these features out to skeptics) but then come to a different conclusion at the end – that science (essentially) does not work.

I often feel that those in this third group – the science deniers – started out in the naive group, and then were so scandalized by the realization that science is a messy human endeavor that the leap right to the nihilistic conclusion that science must therefore be bunk.

Continue Reading »

Oct

19

2010

Perhaps I was naive, but even though I have written about placebos numerous times here and elsewhere I have always assumed that placebo pills were literally sugar pills. It had not occurred to me that placebo content needs to be specifically disclosed, and that their composition might not be as standard as I had assumed.

A new study in the Annals of Internal Medicine reviews clinical trials over the last two years. They found that only 8.2% of clinical trials with a placebo pill as a control specifically disclosed the placebo content. Meanwhile 26.7% of trials involving injections and procedures disclosed the precise nature of the treatment. This difference makes sense, in that there is much more interest in the nature of a placebo treatment when it is more complex than just taking a pill.

The concept of a placebo is that it is completely physiologically inert, therefore any response to the placebo is due to other factors (other than a physiological response to an active intervention). Typically, in pharmaceutical trials, the company that makes the drug being studied will also manufacture look-alike placebos. These can contain the sugar base and any other fillers, the same coating, etc. – but not the active drug. But according to the study authors perhaps we cannot assume that these placebo pills are completely inert.

Continue Reading »

There is a strong scientific consensus that vaccines generally are an effective approach to preventing infectious illness. The vaccine schedule is arguably the most effective and cost effective health promotion intervention ever devised. Vaccines are a public health home-run.

There is a strong scientific consensus that vaccines generally are an effective approach to preventing infectious illness. The vaccine schedule is arguably the most effective and cost effective health promotion intervention ever devised. Vaccines are a public health home-run.